an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

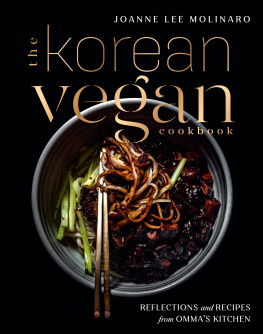

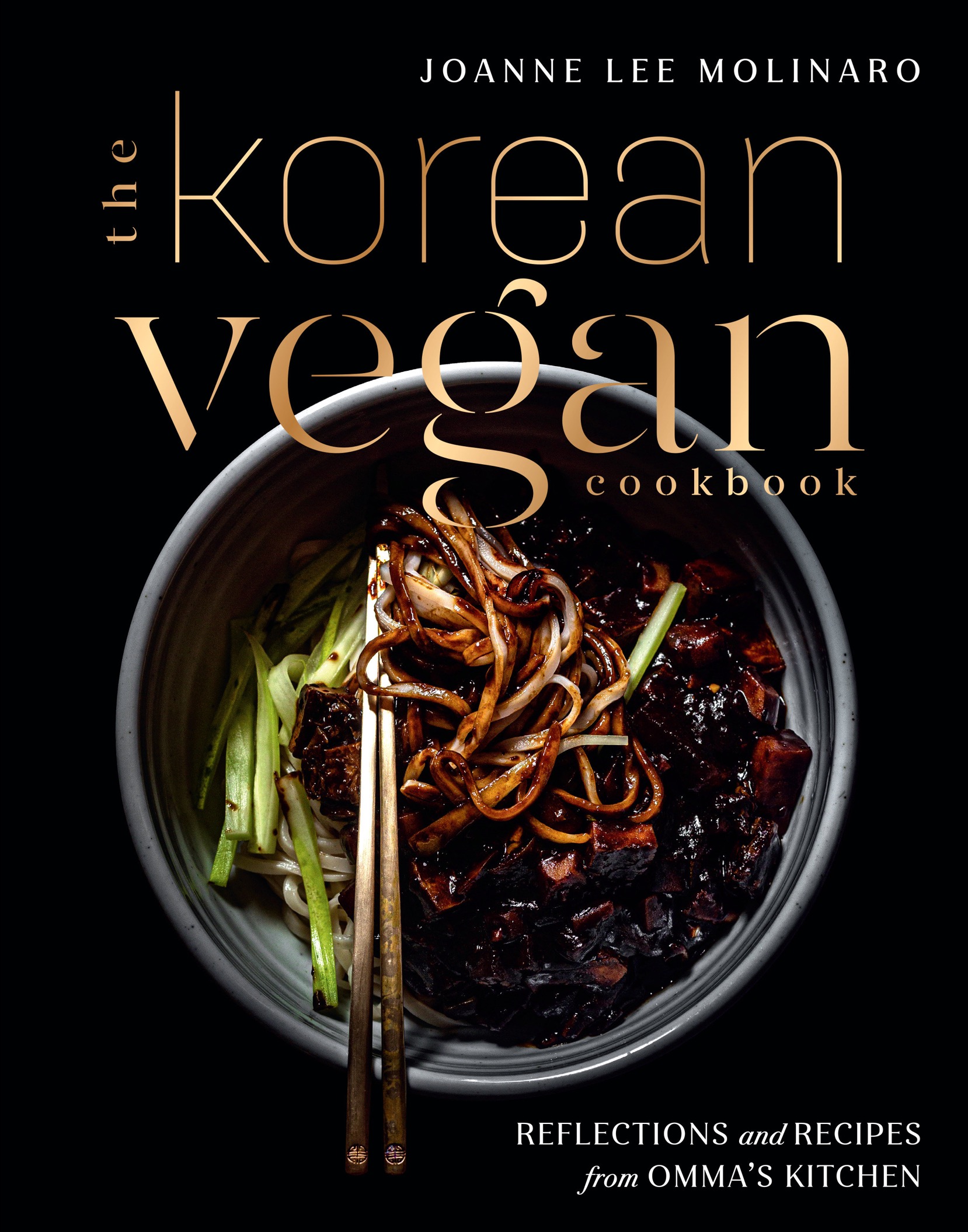

Copyright 2021 by Joanne Lee Molinaro

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lee Molinaro, Joanne, author.

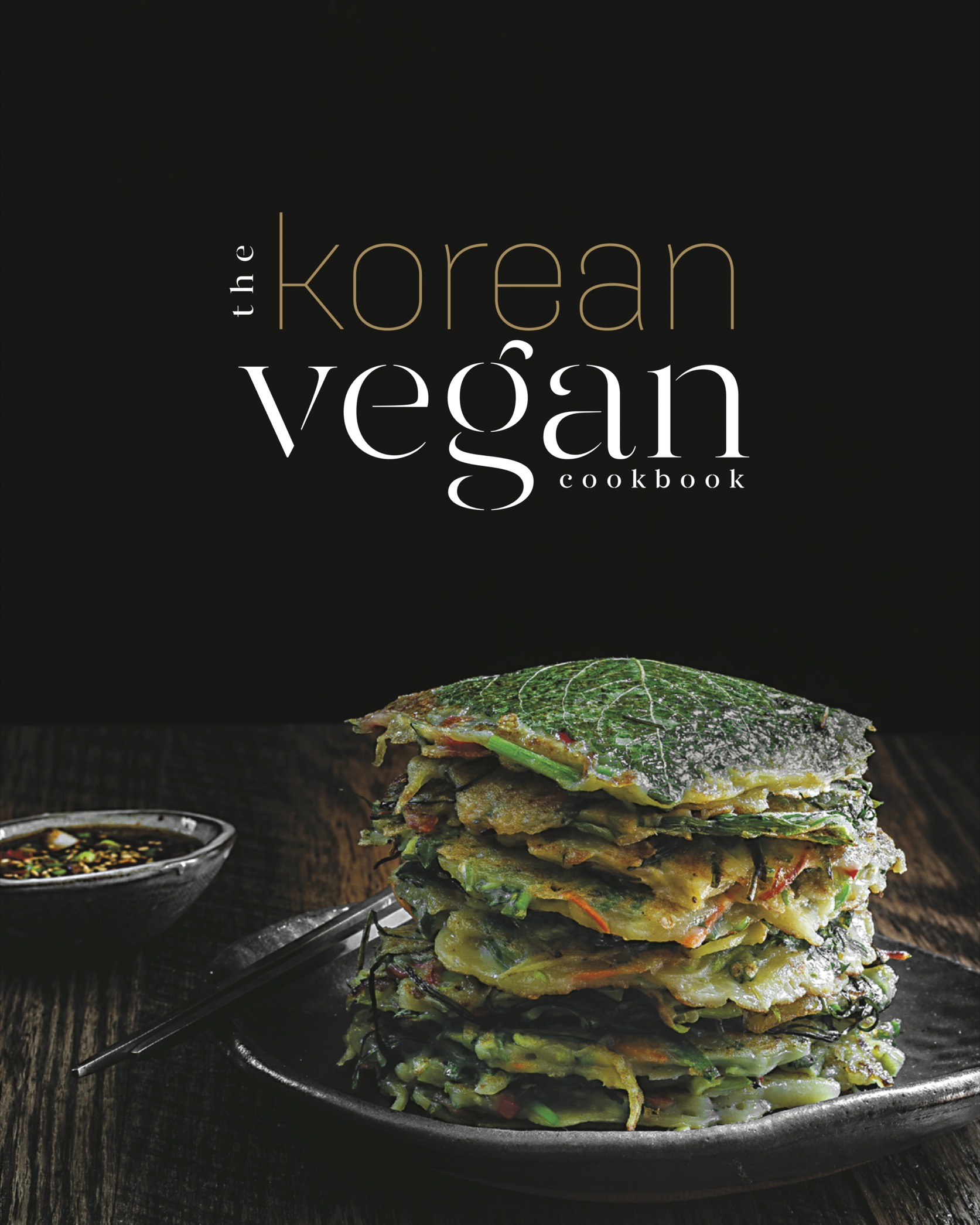

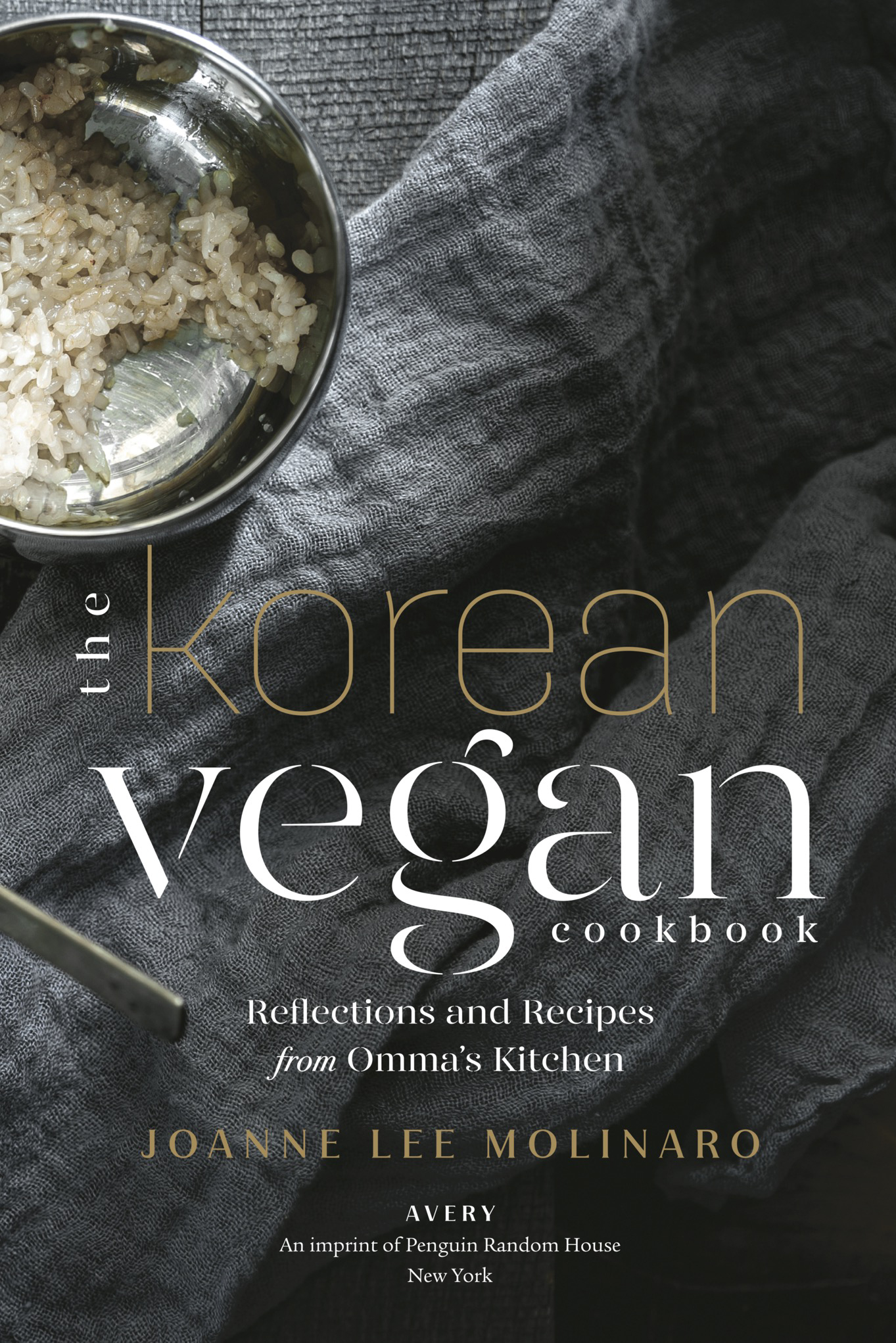

Title: The Korean vegan cookbook: reflections and recipes from Ommas kitchen / Joanne Lee Molinaro.

Description: New York: Avery, Penguin Random House LLC, 2021. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020057487 (print) | LCCN 2020057488 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593084274 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593084281 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Cooking, Korean. | Vegetarian cooking. | LCGFT: Cookbooks.

Classification: LCC TX724.5.K65 L48 2021 (print) | LCC TX724.5.K65 (ebook) | DDC 641.59519dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020057487

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020057488

p.cm.

Book design by Ashley Tucker, adapted for ebook by Estelle Malmed

The recipes contained in this book are to be followed exactly as written. The publisher is not responsible for your specific health or allergy needs that may require medical supervision. The publisher is not responsible for any adverse reactions to the recipes contained in this book.

Author photo by Geoff Martin Photography. All other cover photos by Joanne Lee Molinaro.

pid_prh_5.8.0_c0_r0

To and Daddy, whose stories I treasure.

And to my grandmothers, who I hope are proud of me.

INTRODUCTION

Slurping.

Cautious, but unapologetic.

My father sips a spoonful of the still-bubbling doenjang chigae from the worn ddukbaegi sitting not quite at the center of the table.

Dinner always begins with the clink of my fathers steel chopsticks against a small porcelain plate of banchan, maybe some pickled mung beans or a saddle of kimchi. My brother and I knock our spoons against the sides of our ceramic bowls, which are filled with pearly mounds of rice. My mother plucks a single mung bean from the same small plate my father started with, the silvery chimes of her chopsticks floating toward our low kitchen ceiling.

I can hear the patter of Hahlmuhnees bare feet as she paces from the stove to the kitchen table and loads our bapsang with a basket of fresh kennip, chilies, and squash from the backyard garden, each a different shade of green, a plate bearing a whole roasted fish, and a pitcher of dark-amber, ice-cold corn tea. The worn, ellipse-shaped table we all sit around bears crayon graffiti and wads of gum on its underside but boasts a colorful assortment of more than a dozen banchan.

My spoon and chopsticks remain untouched. Nothing tempts me. Not the doenjang chigae, the chilies Id picked for Hahlmuhnee that morning, or the mung beans my parents favored. This is not what they eat on TV or what the kids at school eat with their families. Why couldnt Hahlmuhnee just make spaghetti once in a while?

Hahlmuhnee

With a grimace, Hahlmuhnee seats herself next to me, finally resting her stiff joints. She reaches for a kennip so dark it looks almost blue, and places it in her open palm. She dabs a pea-size bit of ssamjang into its heart with the tips of her chopsticks. She adds a spoonful of rice before wrapping it up like a small gift she then brings to her mouth. She turns to me, her mouth still agape while she feeds herself, and gives me an inquiring look, as if asking, Why arent you eating? While chewing, she spreads another large kennipso big it extends past her long fingers. Once more, she deposits a bit of ssamjang right in the center, adds a spoonful of still-steaming rice, and smoothly wraps the kennip into a neat green bundle, but this time, presses it toward my mouth.

I part my lips.

The clinks and scrapes and chews and slurps continue for a quarter of an hour, maybe twenty minutes. The mole on Hahlmuhnees chin seems to pulse as she chews another kennip wrap. My mothers pale, angular face remains expressionless, preoccupied, as she brings another spoon of rice to her thin lips. My father closes his eyes as he continues to eat, while my little brothers cheeks are barely visible behind his bowl.

There was predictability in our familys reunion at the end of each day. There was also the serenity that attends the sounds of sustenance. As children of war, scarcity and hunger were embedded in my parents bones long before I began to complain about our lack of McDonalds at the dinner table. As a result, talking was discouraged during mealtime. Eating was a serious business that demanded undivided attention. I dont remember any pleasantries like What happened at school today? or How was work, honey? We didnt spill our guts during dinnerwe filled them.

Sometimes I would help Hahlmuhnee prepare the banchan for dinner. Wed sit on the floor of our foyer with Daddys day-old Korean newspapers spread out and a mountain of raw mung between us. The tails of the sprouts created the appearance of a tangle of blond hair against the black-and-white print, as Hahlmuhnees silver tooth caught rays of sunlight streaming through the screen door.

From left to right: my father, Hahlmuhnee, and my uncle

Once, she shyly counted out the beans we were trimming in Japanese: ichi, ni, sahn, shi. I started copying her: ichi, ni, sahn, shi. She counted to ten, stopped abruptly, and admonished me severely, Its not good to speak Japanese. Its dangerous to speak Japanese. And this is how I learned, for the first time, that there are secrets buried in our family story, ones that Hahlmuhnee thought were too dangerous to say out loud.