Lady Diana Cooper was born on 29 August 1892. She married Alfred Duff Cooper, DSO, who became one of the Second World Wars key politicians. Her startling beauty resulted in her playing the lead in two silent films and then Max Reinhardts The Miracle. In 1944, following the Liberation of Paris, the couple moved into the British Embassy in Paris. They then retired to a house at Chantilly just outside Paris. After Duffs death in 1954 Diana remained there till 1960, when she moved back to London. She died in 1986.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Diana Cooper has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Dedication

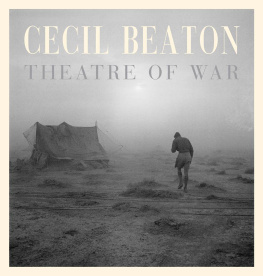

With this and my two earlier volumes I have received more help than I can decently acknowledge. Most of my benefactors will have to remain anonymous, but I feel I must say a special word of gratitude to Flora Russell for allowing me to print so many of her brothers inimitable letters, Martin Battersby for letting me decorate my three books with the epics he painted on my walls, Cecil Beaton for recording so many events in my life and giving me freedom to use the results, and Laurence Whistler for permission to reproduce his brothers letters and drawings.

Norah Fahie has typed and retyped my pencil-scrawled manuscript, repairing my spelling and supplying punctuation. But for her endless care and patience I should never have got into print, and without the loving and ruthless badgering of Jenny Nicholson I might never even have put pencil to paper.

To all these kind friends, and to Rupert Hart-Davis my dear publisher and nephew, I dedicate this last volume.

DIANA COOPER JULY 1960

Illustrations

(photograph Cecil Beaton)

(photograph Cecil Beaton)

(photograph Cecil Beaton)

(photograph Cecil Beaton)

(photograph Cecil Beaton)

(photograph Cecil Beaton)

(photograph Imperial War Museum)

(photograph Cecil Beaton)

(photograph Cecil Beaton)

(photograph Cecil Beaton)

(photograph Cecil Beaton)

(photograph Cecil Beaton)

(photograph Cecil Beaton)

1

Talking through Armageddon

In 1939 the writing so long scrawled on the wall was translated into many languages. The birds of ill omen no longer screeched but perched gagged in the still trees. The voice of Cassandra sank to a whisper. The lull waited for the hour when strife must be hailed, calculation and logic forgotten. We must summon up all our courage and magnify it, and behave well.

To go or not to go to America became our own particularly burning question. When he resigned from the Government after Munich, Duff had signed a lecture-contract for a year ahead, and now October 1939 was here and so was the end-of-the-world war. Duff, irked by his independence and seeing no niche for himself at home, favoured this useful mission to the United States, yet the idea of leaving England in wartime made him hesitate. The oracles he consulted gave diametrically different but not equivocal answers. One augurer felt confident that Duff, a resigned Minister, would shortly be back in office, for already the Government looked rickety; another said that America would resent propaganda. Friendly American journalists like John Gunther and Knickerbocker urged us to go. Winston wavered, unable to admit the Governments instability. Lord Cranborne cried Forward! while Lord Salisbury murmured Back.

My optimistic husband had been to some army manoeuvres in his anachronistic Second Lieutenants uniform. He had wound his puttees tightly round his elegant legs, filled his water-bottle, brushed up his kitbag, and packed it with his few troubles. He had marched off to a field-day, looking as portly as a Secretary of State and jumping with surprise when the Generals called him Sir. By evening he saw that the army held no future for him. His helmet now must make a hive for bees, but a lingering hope urged him to appeal to Colonel Mark Maitland of the Third Battalion, Grenadier Guards (he who twenty years before had shouted Duff off to war from Waterloo). The Colonel dashed his last hope. Now only the Prime Ministers approval of his absence remained to be asked.

The interview was an unhappy one. Mr Chamberlain naturally had no words of sympathy or regret. Duff was surprised at this lack of courtesy. I expected it, but what we did not anticipate was Mr Chamberlains suggesting that in a few weeks time, when things get pretty hot here, a man of fifty might be criticised for leaving his country. Ever since I have maintained that the Prime Minister advised Duff to go for a soldier. I can find no corroboration in Duffs memoirs. I expect that he suppressed or forgot the advice, or else I am guilty of a conscious and vengeful lie that I have come to believe. After a hum and a haw the Prime Minister grudgingly agreed to Duffs going to the United States if he promised to say nothing that might smell of anti-German propaganda. As if Duff was going to talk through Armageddon about Keats or Horace or the Age of Elegance.

The die had been cast in fateful September. John Juliuss day-school in London moved to a less congested county, and together with his familiars he became a boarder at Westbury in Northamptonshire, the best solution for my peace of mind and his untroubled development. In October, with a trembling hand in Duffs, I boarded the American S.S. Manhattan. To Conrad Russell I wrote from Southampton:

The platform was Friths Paddington Station people with all their worldly goods (nothing so pathetic), the guitar, the clock, the old rugs, cricket bats and toy engine. Mine (had I taken any) would be my wax face by Jo Davidson and Queen Victorias picture of Mother, your diamond dolphins and what not? The Frith scene made me see ourselves as Ford Madox Browns