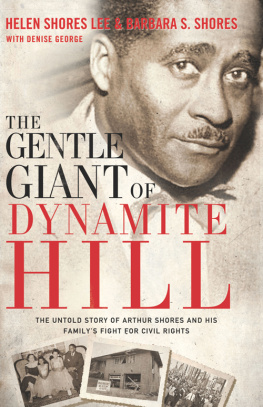

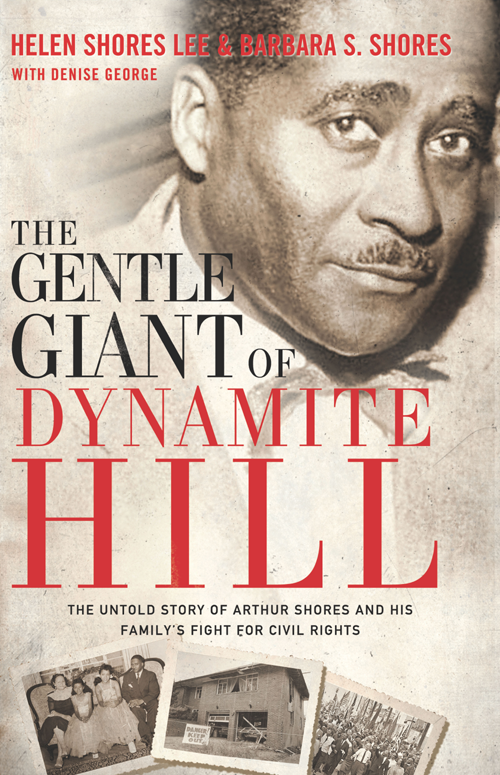

THE

GENTLE

GIANT OF

DYNAMITE

HILL

THE UNTOLD STORY OF ARTHUR SHORES AND HIS

FAMILYS FIGHT FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

HELEN SHORES LEE & BARBARA S. SHORES

WITH DENISE GEORGE

For Mummee and Daddy,

and our children and grandchildren

The LORD is my light and my salvation

whom shall I fear?

The LORD is the stronghold of my life

of whom shall I be afraid?

(PSALM 27:1)

Contents

Epilogue 1A Personal Memory

by Judge Helen Shores Lee

Epilogue 2A Personal Memory

by Barbara Sylvia Shores

They called Stephen Douglas, who famously debated Abraham Lincoln, the Little Giant, but that sobriquet is better suited to Arthur Davis Shores, who stared down Jim Crow segregation in his native Alabama and won a great victory for his nation. His story is at last and lovingly told by his daughters, Helen Shores Lee and Barbara Sylvia Shores. The story they tell is accurate and balanced, but it has the added value of firsthand memory of the man and his times. It is also the story of their Mummee, Theodora Helen Warren Shores, his life mate, who endured the bomb blasts and kept her eyes on the prize her husband worked so hard to win. So it is the story of a family that both encouraged and experienced the greatest social transformation in American history.

Arthur Shores could be called the Little Giant for the same reason as was Douglas: he was short of stature but long on accomplishment. He was a handsome man, and as I once described him, a darker version of Errol Flynn, complete with a pencil moustache. Although he took on the most vexing cases of civil rights in a state determined to maintain white supremacy at any cost, he was forever calm, the eye of the storm of change. In what many called the most segregated state in America, he was the architect of the legal challenge to segregation: from equity pay for teachers (meaning African American teachers should earn the same as whites), to voting rights, and finally to equal public accommodations.

His greatest triumph came with the desegregation of the University of Alabama. On that June day in 1963, Alabama became the last state to maintain a vestige of legal segregation, although it was the first state ordered to desegregate under Brown v. Board of Education. It was Arthur Shores, aided by Thurgood Marshall and Constance Mobley of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, who won the right for Autherine Lucy and her friend Pollie Anne Myers to become the first African American students at the University of Alabama. Although their rights were denied by violence at the university and intransigence by the universitys trustees, Shores would ultimately win out when Vivian Malone and James Hood walked past George Wallace at the schoolhouse door. It was Shoress most gratifying victory.

But Shoress aim was always to win, not conquer. While he enjoyed watching white lawyers squirm as they tried to fit constitutional equality into the procrustean bed of racial politics, Shores remained composed. He knew he would win if the law were constitutionally applied, and increasingly it was. Shores could get along with anyone, even George Wallace, the states and the nations chief champion of segregation. Described in this book is a scene where Wallace, as a judge before becoming governor, invites Shores to have lunch with him in chambers because Jim Crow facilities made it impossible for the Little Giant to eat elsewhere. Shores understood the changeable side of the white South, even of George Wallace; and when it was all over, Wallace spent the rest of his days asking for forgiveness, which black Alabamians gave in full measure even if they could not forget.

Shores would go on in 1968 to become the first black city councilman in the Souths most segregated city, Birmingham, thus fulfilling another political dream. He would serve until 1978, when he took a much-deserved retirement from paying civic rent. He would also earn an honorary doctorate from the University of Alabama in 1975, and this writer, in the early 1990s, had the honor of commissioning a portrait of him for the universitys main library, where today he smiles down on a grandson, Damien Larkin, who is completing a doctorate.

What the daughters have accomplished in this book is the portrait of a Giant, no qualifiers needed.

E. CULPEPPER CLARK, Dean

Henry W. Grady School of Journalism and

Mass Communication, University of Georgia

TRIBUTE

To Daddy

Theres joy in our hearts, Daddy, knowing you set a fine example as you patiently taught us your lessons of life.

You taught us to be strong enough to cope with disappointments and hard times, and strong enough to live with any weakness we may have.

You taught us courageto be brave enough to do what we believe is rightto know that fear is natural, but not to let it stop us from doing what we must.

You taught us the value of knowledge so that we would be prepared to make decisions, big and smallso that when we made mistakes, we would try to learn from them and then go on from there.

But most of all, you taught us about love by setting an example with your own gentleness and openness and warmth.

You enriched our lives forever with your lessons and your love

And we thank you from the bottom of our hearts. Helen and Barbara

(Written by Helen Shores Lee and Barbara Sylvia Shores on Friday, December 20, 1996, on the Obituary Order of Service of Arthur Davis Shores)

CHAPTER 1

Why, Daddy?

1953, at our home on Birminghams

Center Street on Dynamite Hill

(Helen remembers.)

Daddy, why is it legal for someone to harass us, but not legal for us to respond back to them?

HELEN SHORES LEE, 12,

Birmingham, Alabama, 1953

I can still recall the pinging sound bullets made when someone in a passing car shot the window in our recreation room. The thick glass usually prevented the window from shattering, but the bullets would pierce through and lodge in our interior walls. Each bullet made its marka small hole through the glassand each bullet brought our mother fresh new fear.

In 1953 I was twelve years old, living with my father, mother, and younger sister, Barbara, in Birmingham, Alabama, an old steel-producing city and the hotbed of racial injustice and violence in the United States. Shortly after World War II, the invisible line that supposedly divided black homeowners from white homeowners began to blur. Black residents built their homes a little too close to the white community, and the white-sheeted Ku Klux Klan tried to scare black residents from the area by bombing their homes. Our neighborhood had had so many unsolved, Klan-related bombings that people dubbed our street Dynamite Hill, yet none of these bombers ever faced arrest or punishment.

Our ranch-style brick house had a good-sized grassy front yard, a fenced-in backyard for Barbaras beloved dogs, and a large thick picture window in our living room and recreation room facing Center Street. In the evenings my dad, mother, sister, and I often sat in the recreation room together and watched television. If it was a Saturday night, together we enjoyed my dads favorite meal, hot dogs with mustard and fresh-squeezed lemonade.