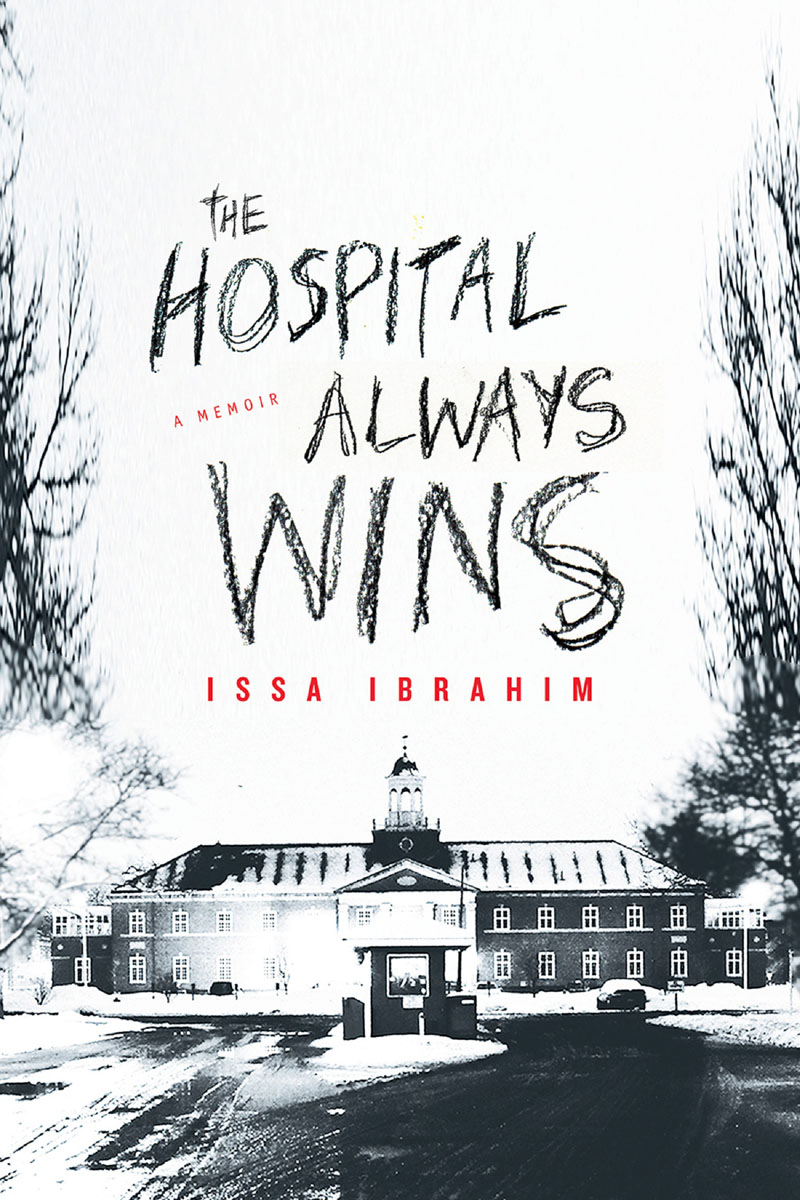

ISSA IBRAHIMS memoir details in searing prose his development of severe mental illness leading to a horrific family tragedy, his acquittal by reason of insanity, and his subsequent commission to a mental hospital for nearly twenty years.

Raised in an idyllic creative environment, mom and dad cultivating his talent, Issa watches his familys descent into chaos in the drug-crazed late 1980s. Following his fathers death, Issa, grief-stricken and vulnerable, travels down a road that leads to psychosisand to one of the most nightmarish scenarios conceivable.

Issa receives the insanity plea and is committed to an insane asylum with no release date. But that is only the beginning of his odyssey. Institutional and sexual sins cause further punishments, culminating in a heated legal battle for freedom.

Written with great verve and immediacy, The Hospital Always Wins paints a detailed picture of a broken mental health system but also reveals the power of art, when nurtured in a benign environment, to provide a resource for recovery. Ultimately this is a story about survival and atonement through creativity and courage against almost insurmountable odds.

Copyright 2016 by Issa Ibrahim

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61373-512-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Is available from the Library of Congress.

Interior design: Jonathan Hahn

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

For Mom,

who nurtured and protected my creativity, and mental patients everywhere.

The story you are about to read is all true. Names have been changed to protect anonymity and deter the litigious.

1

O H , M A , WHAT AM I G ONNA DO ?

Im working on my latest painting, a large unstretched canvas tacked to the main wall of my place. Mom enters dancing and keeps in step with the ska, one of many retro musical touchstones that I embraced as a black teenage new waver and now, forty years later, am reluctant to let go of. Mom identifies with it too, being of Jamaican/English roots. She calls out, Keep working, son, youll get it, beaming with pride while gingerly pinching a joint. Guiding me through this artistic roadblock and recurring waves of memory and regret, Mom skips and shimmies, pleased at my persistence. I smile too, my mood lifted.

Less a haunting than a benevolent visitation, Mom is just as I remember her. Small but matronly, mercurial and frisky, moving like an amalgam of bohemian and dervish, seven-veiled Scheherazade and Salome, lost in the rhythm, possessed by melody, body swaying and arms waving. Never missing a beat or dropping an ash, she prowls as her reefer smoke swirls around her like the brimstone of a magician on the verge of a daring feat of prestidigitation.

When I was growing up, Mom, like my older sisters, was quite the mystic, proficient in tarot reading and astrology, treating me as an unknowing subject for pot-inspired soothsaying and prognostications. I was earmarked for greatness, or so the cards kept coming up and my chart seemed to indicate, yet I was oblivious to the doting, the preparations, and the expectations. But being born IssaArabic for JesusI had a lot to live up to.

The music is crosscut and drowned out, augmented and bastardized, by the constant bass and drum thuds that emanate from more than one loud sound system in my apartment building. The sounds continue farther down the block and into Richmond Hill, Queens, New York, a Trinidadian/Guyanese/Indian neighborhood. The music is busy, drunk, designed to get you to shake your ass and get some ass by the end of the night. The cacophony created by two or three of these deranged DJs, battling it out for bragging rights, is a true jungle of call-and-response beats, booms, and blares punctuated by unintelligible shouts, rambling and incongruous sound effects, and the occasional wail of females beckoning for a big stiff dick. As Im not from that part of the world and am a wee bit older now, and as I was weaned on the genteel pop of the Beatles, Burt Bacharach, and the Beach Boys, I bristle at the musical mlanges descent into outright noise. Yet when it does quiet down, in the post midnight hours, I can play my own songs, bluesy, insular freak-pop creations about my hard-knock life and how Ive survived it, and make my own kind of din. And when I do Mom says, I like the sound of that, listening close, head cocked and eyes narrowed to parse the details. You may be on to something, son.

When not writing or recording, Im immersed in painting. The magic happens after 10 PM . I am usually up till dawn and have grown used to painting quickly and not sleeping until I am finished. Its a habit I developed out of necessity, when for twenty years I had to work on my craft from the last evening head count till the morning wake-up call, at which point thirty other mental patients and I had to exit our bedrooms for breakfast and a full day of programming.

2

I T S A LOVELY, CRISP SPRING MORNING . I arrive at Kew Gardens Court a bit early, at 8:30 AM , so Miss Debra, my escort and a very pleasant, matronly, and supportive treatment aide Ive known for years, suggests we go to the deli across the fearsome Queens Boulevard. There, where we sit for a moment with coffee and breakfast sandwiches, we encounter Judge Freed. He is cordial and upbeat, valise in one hand, morning Times in the other, topcoat slung over his arm, wearing a dark wool suit and sporting a colorful tie, which has become his trademark over the course of the trial. Large in stature but not intimidating, he drops his head and peers at me above his bifocals, then smiles.

I believe Judge Freed has heard my case and I hope he has gone over the testimony very carefully, ready today to render a fair and just decision. He impressed me from the very beginning as a wise, rabbinical fact-finder and I hope my instincts are correct. My mind races as he orders his morning meal. Should I hit him up for information on where his axe will fall? Opting to play it cool, I sit and drink my coffee and say nothing more than Good morning, Your Honor.

In the courtroom, the spindly attorney general walks in at about 9:50. He informs me, through my escort, that Judge Freed has called the Mental Hygiene Legal Service office at Creedmoor. Mr. Ibrahims lawyer should be here closer to noon. This means a long wait but as Ive waited almost twenty years for this, another two hours wont hurt.

At 11 AM , my stand-in MHLS attorney Leslie Boobala enters. We have never formally met but I recognize her face from her trips into Building 40 visiting other patients. She shares a suburban ordinariness with all the MHLS attorneys, saving her firebrand liberal warrior stance for the courtroom and the cases she believes are worth it.

I dont know if I will need her for any negotiations, and she asks, Are there any stipulations that you want me to argue if it comes to that? I hand her the list of demands that my now-retired MHLS attorney Barry and I cooked up that I could live with for Level 4, unescorted off-grounds privileges, if that is where Judge Freed would lean. Leslie reads the printout but says nothing.

I still would like to hear Judge Freeds decision, though, I say, aware that only discharge or retention are on the table. I have hope that I made my case.

OK, I hear you.

We sit in silence for about an hour, watching Judge Freed dole out justice in two quick cases. He then says, I see Mr. Ibrahim is here, and his attorney is here, and the attorney general is present. All we need now is Mr. Mullin, the district attorney, and we can proceed. It is a very lengthy verdict and I need to put it all together, so if we can get in touch with the DA, and you can give me another, say, fifteen minutes, we can proceed.

Next page