The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Charlotte

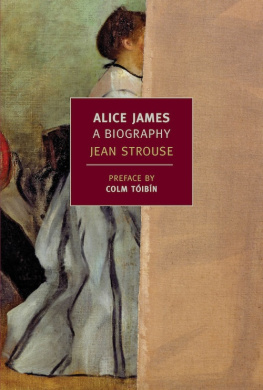

INTRODUCTION: A CONTEMPORARY PORTRAIT OF THE JAMESES

Success has always been the biggest liar great men, as they are venerated, are bad little fictions invented afterwards.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

In everything they undertake they do well and often excellently; they are admired and envied; they are successful whenever they take care to bebut all to no avail. Behind all this lurks depression, the feeling of emptiness and self-alienation, and a sense that their life has no meaning.

Alice Miller, The Drama of the Gifted Child

When you travel, your first discovery is that you do not exist.

Elizabeth Hardwick, Sleepless Nights

Late in his life, the American expatriate novelist Henry James longed to memorialize his entire remarkable family, all of whom remained poignantly alive in his imagination. We were, to my sense, the blest group of us, he wrote in his autobiography in 1913, such a company of characters and such a picture of differences so fused and united and interlocked, that each of us pleads for preservation. But although there have been admirable James biographies, it has been difficult to break through the decorum of the family and even their finest chroniclers to truly capture this iconoclastic group, whose oversized collective achievementsas great as those of any other family in American historygrew out of a very troubled, impassioned, and often dysfunctional home life.

Some of the Jamesesa close-knit New York dynastyended their lives as depressed and disappointed bankrupts; others became eminent writers whose wit and invention helped lay the foundations for what we now think of as modern America. The family is best known for its two eldest sons, Henry James Jr. and William James, the philosopher and psychologist. The formers sumptuous fictions about Americans in Europe The American (1877), The Portrait of a Lady (1881), and The Wings of the Dove (1902), among many otherscaptured the glittering international world of the so-called Belle Epoque, the beautiful epoch between the Civil War and World War I. Henry James epitomized high literary achievement, and his works, known for their psychological depth, have been seen as groundbreaking modern classics. Only a shade less well known than his brother, William James established a considerable reputation as a pioneer of modern psychology and as a proponent of pragmatisma characteristically American philosophy that empowered each individual to determine his or her own truths.

History has immortalized these brothers in isolation and has only secondarily considered them in the light of their less prominent relatives and the struggles those relatives embodied. Critics have sometimes regarded William and Henry as grand self-generated geniuses in their respective realms, as figures who stood above their family circumstances. But Nietzsches warning about success obscuring the real complexity of famous lives applies well to these two American icons. Suffering and deep human complexity fueled their work, and for six decades the two men remained remarkably close, engaged, and competitive blood brothers. They were locked in a lifelong relationship that weirdly echoed their parents marriage and whose turbulent and complex dynamics crucially shaped their most famous books.

Besides Henry and William, the James clan contained other figures who have also fascinated many: Henry James Sr., their father, was a rebellious prophet of American social reform; their sister, Alice James, was a career invalid and clandestine diarist who documented her own struggles in an extremely male-oriented family and society. But these two additional Jameses, reclaimed and recovered only in the last few decades, are just the beginning of the family story. I believe that all seven of the Jamesesthe parents and their five extraordinary childrenwere in fact so fused and united and interlocked that it is impossible fully to understand any one of them without the rest, without investigating the moving drama of their complex family life that unfolded in some of the most interesting cities of the eraNew York, Newport, Boston, London, Paris, and Romebetween the social upheavals of the 1840s and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

For years, the Jameses lavished on one another a rich moveable feast of family life. Their fathers intellectual ambitions and shifting moods swept them capriciously from city to city, continent to continent. When the five children were still young, before constant mobility had become the American norm, the family moved through Europe and America like vagabonds, surviving years of shifting houses, hotels, and boarding schools knitted together by long rail journeys and Atlantic steamship crossings. Traveling continually, with only the family for stability and continuity, they alternately adored, defended, and excoriated one another with an intensity that only people who passionately love each other can generate. They became the only real country, as William James later put it, to which any of them ever belonged.

Driven to leave his mark on the world as well as to travel, Henry Senior passed on many of his obsessions to his children; with high expectations and elusive approval, he helped spur them all toward the anxieties of overachievement. Henry Junior and William James were especially caught up, but their less famous siblings were not immune to it. Their superhuman efforts to be seen, acknowledged, and understood dominated their private and professional lives, spawning grandiose plans, remarkable accomplishments, and deep, long-lasting depressions.

Somewhere between the Alcotts and the Royal Tenenbaums, the Jameses come into the American story and add much to our perception of it. In their ambitions, ambiguities, and affectations, the Jameses can strike us as curiously contemporarythe forerunners of todays Prozac-loving, depressed or bipolar, self-conscious, narcissistic, fame-seeking, self-dramatized, hard-to-mate-or-to-marry Americans. This side of the Jameses has often been downplayed, and much of the story has remained untold, buried under generations of propriety, convention, and veneration. But the Jameses dysfunction sheds crucial light on the origins and full range of their influential achievements. Henry Seniors bold social experiments, Henry Juniors exquisite fiction, Alices exploration of womens hidden lives, and Williams seminal contributions to American psychologyall grow directly from this sometimes unseemly experience. Accordingly, this book is an effort to interpret these people by way of their interior family and household experience, as Henry James himself longed to do, and to understand their hidden passions and vulnerabilities both as deeply moving and highly relevant to our own present-day lives.

* * *

IN NEW YORKS Washington Square, you can still see scraps of the Jameses family world: cast-iron railings, steep steps, porticoes, and fanlights. Back when I was an undergraduate, I roamed expectantly with an old address, hoping to look them up, hoping to establish a personal link. For years, Ive collected James houses: on Beacon Hill, on the rue St.-Honor, in St. Johns Wood, at Newport, at Chocorua, in New Hampshire. With Henry Seniors determination to give his family a sensuous education, each house represented a slice of his experiment in unconventional living, each a new phase of the familys remarkable development. Most of the numerous James residences are ghostly now, thanks to the American mania for tearing down and rebuilding that Henry James so deplored in The American Scene. (I was almost as shocked as he was to discover that both his mothers house in Washington Square and his birth house in nearby Washington Place no longer exist.) Of some of these houses, not even a photograph remains; they were ordinary domestic properties, part of the family life of the nineteenth century that almost nobody bothered to document.