Early praise for

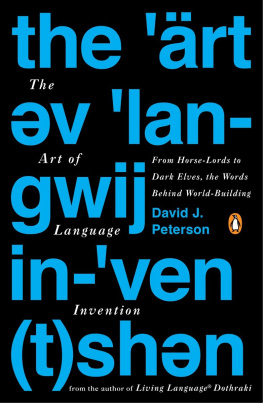

THE ART OF LANGUAGE INVENTION

David J. Petersons The Art of Language Invention accomplishes a minor miracle in taking a potentially arcane discipline and infusing it with life, humor, and passion. It makes a compelling and entertaining case for language creation as visual and aural poetry. I cherish words, I love books about words, and for me this is the best book about language since Stephen Frys The Ode Less Traveled . And, best of all, theres a phrasebook!

Kevin Murphy, co-creator and showrunner of Syfys Defiance

If you want to know how someone makes up a language from the ground up, youll find out how in this bookand the glory of it is that along the way youll get the handiest introduction now in existence to what linguistics is. In fact, read this even if you dont feel like making up a language!

John McWhorter, author of The Language Hoax

Accessible, entertaining, and thorough, Peterson has created an invaluable resource for authors, dedicated fans, and casual enthusiasts. This is the book I wish Id had when I started writing.

Leigh Bardugo, New York Times bestselling author of Shadow and Bone

This book not only lucidly ushers language invention into its own as an art form, its also an excellent introduction to linguistics.

Arika Okrent, author of In the Land of Invented Languages

George R. R. Martin created Drogo, and David Benioff and Dan Weiss believed in me, but David Peterson gave me life.

Jason Momoa

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE ART OF LANGUAGE INVENTION

DAVID J. PETERSON was born in Long Beach, California, in 1981. He began creating languages in 2000, received his M.A. in linguistics from the University of California, San Diego, in 2005, and cofounded the Language Creation Society in 2007. The inventor of numerous languages for television, film, and novels, he is best known for creating Valyrian and Dothraki for HBOs hit series Game of Thrones, adapted from George R. R. Martins A Song of Ice and Fire series. He is the bestselling author of Living Language Dothraki:A Conversational Language Course Based on the Hit Original HBOSeries Game of Thrones. He has also created languages for Syfys Defiance and Dominion, as well as Thor 2:The Dark World and the CWs Star-Crossed and The 100.

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

Copyright 2015 by David J. Peterson

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Ayeris Tahano Hikamu script used by permission of Carsten Becker. Carsten Becker, 2014.

Sondiv (or Atrian) language from Star-Crossed television series. Courtesy of CBS Studios Inc.

The Dothraki and Valyarian languages from the HBO original series Game of Thrones. 2011 Home Box Office, Inc. All rights reserved. HBO and related service marks are the property of Home Box Office, Inc.

Dark Elf language appears courtesy of Marvel Studios.

Phrases from the SyFy television program Defiance appear courtesy of NBCUniversal Media, LLC.

Minza text from Conlang Relay 13 used by permission of Herman M. Miller. 2006 Herman M. Miller.

Rikchik language used by permission of Denis Moskowitz. Copyright 19972014 by Denis Moskowitz.

Sakhii Widoshni (Naming Ceremony) illustration used by permission of Trent M. Pehrson. 2014 Trent M. Pehrson.

Klens Ceremonial Interlace alphabet used by permission of Sylvia Sotomayor.

Da Mtz se Basa language from 13 th Conlang Relay used by permission of Henrik Theiling.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CA TALOGING IN PUBLICAT ION DATA

Peterson, David J., 1981

The art of language invention : from Horse-Lords to Dark Elves, the words behind world-building / David J. Peterson.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-698-15567-1

1. Languages, Artificial. I. Title.

PM8008.P48 2015

499'.99dc23 2015003967

Cover design: Colin Webber

Version_3

For Erin

Contents

Introduction

The first time I heard a language of mine spoken on-screen was at a cast and crew premiere event for the first season of HBOs Game of Thrones. It was a lavish, but, comparatively speaking, poorly attended event. George R. R. Martin was there, but many of the seats reserved for cast members in the Ray Kurtzman Theater remained vacant throughout the screening of the first two episodes of the series. Needless to say, they didnt know how big this thing would get (who did?), but I appreciated the extra legroomand the front-row seat.

My initial reaction to hearing Dothraki, the language of the long-braided, horse-riding warriors, though, was one of dismay. The first line one hears in the series is in the pilot, when Illyrio Mopatis, welcoming Khal Drogo and his band into his courtyard to arrange a marriage, says Athchomar chomakaanWelcome when said to one person. I misremembered how Id translated it, though, and thought he should have said Athchomar chomakeaWelcome when said to more than one person. So even though Roger Allams performance was fine and it was I who was mistaken, I was a little miffed. After the screening had finished we all got in line to congratulate David Benioff and Dan Weiss on a successful premiere, and when they asked me how the Dothraki speakers did, my face must have betrayed me, for David said to me, You know, we [i.e. he and Dan] were talking, and we realized, if any of the actors made a mistake, who would know itexcept for you?

This is actually a question Ive gotten a lot since. That is, if theres an actor performing in a created language that no one speaks, who will know if they make a mistake aside from the one who created the language? From experience, I can tell you that the actors always know (and it frustrates them when the takes with errors make their way into the final cut), but let me focus on the audience.

If you, as a viewer, sit down and listen to one line from a created language and nothing else, its nearly impossible to tell if its a created language, a natural language one doesnt know (one that exists in our world), or gibberishto say nothing about whether or not the actor gets all the words right. If thats the extent of the linguistic material in the production, it doesnt matter what work went into creating the line.

As the number of lines increases, though, the odds of the casual audience member picking up on inconsistencies increase. Its not every fan who pays attention to what actors are saying in a language they dont understand, but there are those who do. Furthermore, television shows and movies arent playsthat is, they arent events that happen at one moment in time and are never seen again. If the general public is anything like me, most of the television and movie viewing they do now isnt done liveand if a show is worth its salt, theyll watch it again and again and again and again.

As a language creator, I always had a bit of a different perspective. When I was creating Dothraki, I wasnt creating it simply to fill out the requisite non-English dialogue. I had an idea that Game ofThrones could be big, and could occupy a special place in television historyjust as George R. R. Martins books already do occupy a special place in the history of fantasy. The work I was doing, then, would need to be something that would stand the test of time. Because even if a fan whos never heard of the books cant tell if one actor makes a mistake in the premiere on their first viewing, fans five, ten, twenty years from now