INTRODUCTION

A ll living beings on earth share the same fundamental need: to eat for survival, be it by foraging, gathering or killing prey. However, it is how we as humans satisfy this need and what we do with food that set us apart from other creatures. We are the only species that knows how to farm and how to tame our sources of food. It has taken us hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of years to evolve from mere hunter-gatherers to agriculturalists, from eating raw molluscs to enjoying refined cuisines. Each individual or group has a different way of dealing with the need for sustenance, so the treatment of food can be a door through which to catch a glimpse into a peoples culture, their view of life and afterlife, and their expectations, hopes and despair. To know what a people eats is to understand how its society works, why it goes to war or sues for peace. To understand how a group of people eat is to acknowledge how they both differ from and are similar to oneself.

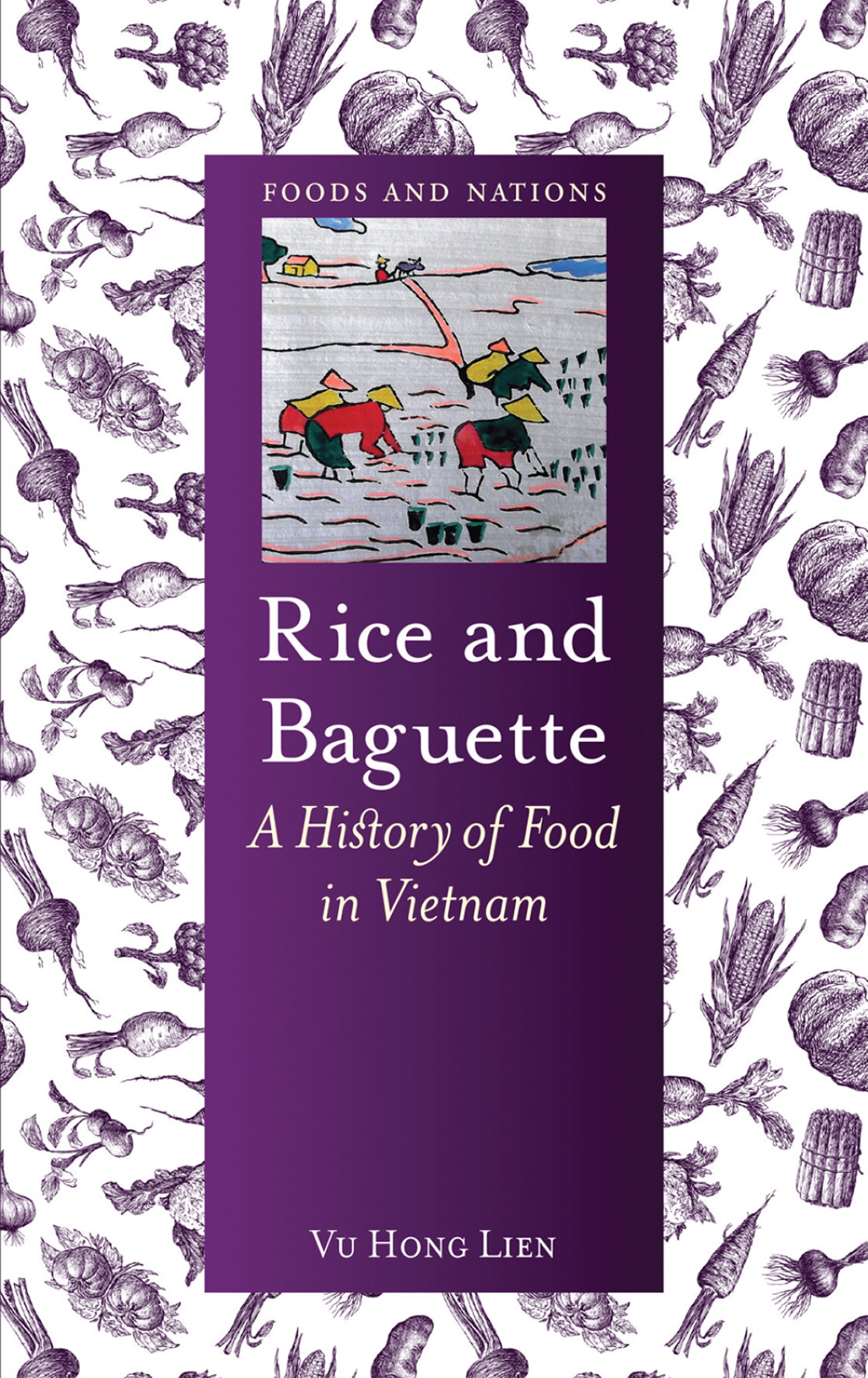

The people of Vietnam have undertaken a long journey to arrive at the diverse food culture we know today, starting from the time when Homo sapiens first set foot on this coast of Asia and decided to settle, more than 70,000 years ago. The journey has been complex and full of surprises, but its destination is probably the most surprising feature of all. It points to the fact that if modern Vietnamese food had a voice, it would be bilingual, for it is the offspring of a marriage of convenience between a rice-based diet and a wheat-based culture. Todays Vietnamese cuisine is a mixture of French and Vietnamese dishes, adapted and modified to suit and complement one another.

This startling statement is bound to offend those who have always believed that Vietnamese culinary culture is subject to the palate of its Chinese big brother, considering that the Chinese colonized and occupied the original land of Viet (todays north Vietnam) for almost ten centuries, from 111 BCE to the middle of the tenth century CE. But Chinese cuisine, though important in Vietnam, exists as a separate tradition. It is a type of food for such important events as weddings and other landmark occasions. In contrast, when the French colonists brought their own cuisine to Vietnam in the second half of the nineteenth century, many of the dishes were instantly successful. The Vietnamese embraced them wholeheartedly, Vietnamized them with local ingredients and happily consumed them as a natural part of their diet. Ragout, stuffed tomatoes, pt, mayonnaise and so on were incorporated into everyday Vietnamese food, and each acquired its own local pronunciation and usage. Most remarkably, the Vietnamese loved the crunchy bread stick known as baguette. As bnh m (wheat cake), it became the most cherished legacy of the French in Vietnamese cuisine. Having said that, as popular and cherished as bnh m is, a square meal for most, if not all, Vietnamese people is still a meal with rice. Rice and its by-products have been around for millennia, since the prehistoric Vit lived on the deltas of the Hng, M and C rivers. When they started eating the wonder grains they first found in the wild, their diet, lifestyle and social structure changed for ever.

Map of Vietnam.

Rice and Baguette is the story of what the Vit have eaten throughout history, and of why and how they eat certain types of food. It recalls the many thousand years of Vietnamese progress from mollusc-eaters to hunter-gatherers to agriculturalists. It tells of their struggle to tame nature and to adapt to it, and of their failures and successes in winning the most crucial element for life: food.

ONE

From Molluscs to Venison

H umankind has existed for millions of years, in different forms, but we became farmers only in about 10,000 BCE, when the last Ice Age ended and the earth gradually became warmer. In Vietnam, the new balmy climate allowed the cave-dwelling prehistoric Vit people to venture further afield to hunt, gather and try new types of food. In the course of these adventures, they discovered how to take the food sources home in order to experiment with growing or taming them. It was only in the twentieth century that we became able to date certain archaeological evidence with the help of modern technology. Traces found at various sites in the Red (Hng) River delta in present-day north Vietnam show that the first rice agriculturalists could have existed in about 2000 BCE. This date coincides with that of various Vietnamese legends and is supported by later scientific analyses of rice grains and pollen. That is not to say that the prehistoric Vit did not know about rice and other agricultural products before then; it is just that archaeological evidence has not shown reliably whether the products they ate before this date were wild or domesticated.

In fact, the proto-Vit people might have known how to cultivate rice long before 2000 BCE, since it is generally believed that the ancient land of Vit included part of southern China. Archaeological sites in China have shown that rice was grown south of the Yangtze River from about 8000 BCE on. This area has now been accepted by many geneticists as the cradle of the rice variety of East and Southeast Asia,