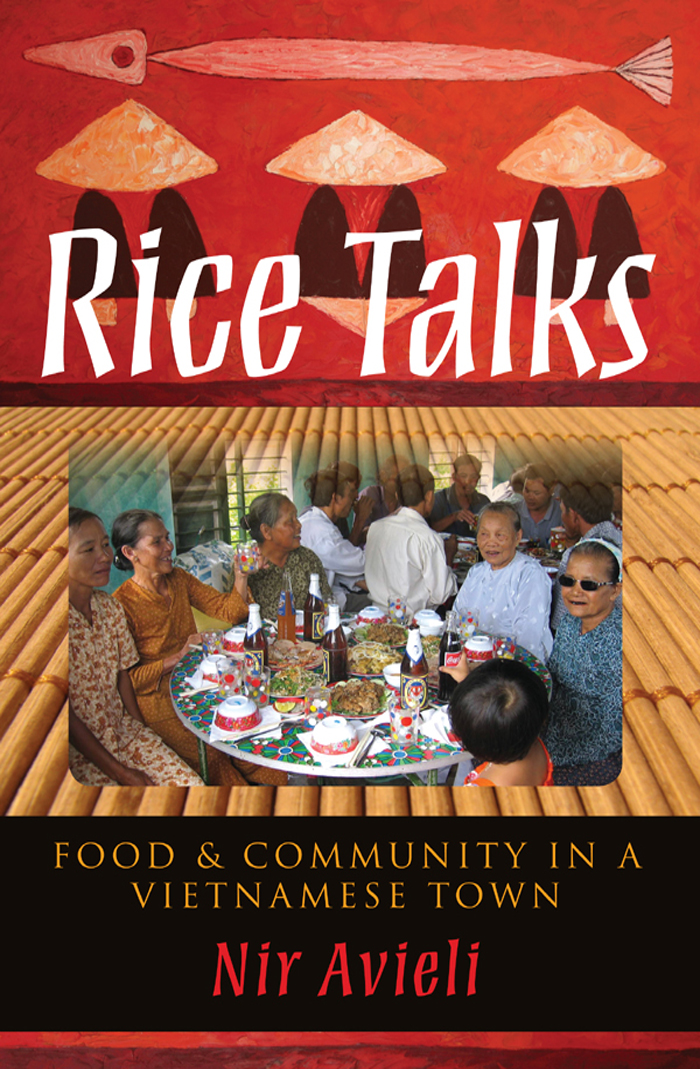

Rice Talks

Rice Talks

FOOD AND COMMUNITY IN A

VIETNAMESE TOWN

Nir Avieli

Indiana University Press

BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, Indiana 474043797 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders | 8008426796 |

Fax orders | 8128557931 |

Orders by e-mail | iuporder@indiana.edu |

2012 by Nir Avieli

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photo copying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data

Avieli, Nir.

Rice talks : food and community in a Vietnamese town /Nir Avieli.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780253357076 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780253223708 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780253005304 (e-book) 1. Food habitsVietnamH i An. 2. FoodSocial aspectsVietnamH

i An. 2. FoodSocial aspectsVietnamH i An. 3. Gastronomy VietnamH

i An. 3. Gastronomy VietnamH i An. 4. Cooking, Vietnamese. 5. H

i An. 4. Cooking, Vietnamese. 5. H i An (Vietnam)Social life and customs. I. Title.

i An (Vietnam)Social life and customs. I. Title.

GT2853.V5A85 2012

394.12095975dc23

2011028385

1 2 3 4 5 17 16 15 14 13 12

To my parents Elyakum

(19372004)

Aviva

Contents

Preface

Food, like the air we breathe, is vital for our physiological survival. Food is also the most perfect cultural artifact, the outcome of a detailed differentiation process, whereby wheat grains are transformed into French baguettes, Italian pasta, or Chinese steamed buns, each encompassing a world of individual, social, and cultural identities: The way any human group eats, Claude Fischler (1988: 275) points out, helps it assert its diversity, hierarchy and organization food is central to individual identity, in that any human individual is constructed biologically, psychologically and socially by the food he/she chooses to incorporate.

The power of food is epitomized by the process of incorporation (literally, into [the] body), in which culturally transformed edible matter crosses the borders of the body (ibid. 279) and breaches the dichotomy between outside and inside, between the World and the Self. No other cultural artifact penetrates our bodies with such immediacy and thoroughness. As Brillat-Savarins aphorism You are what you eat suggests, when we eat we become consumers (and reproducers) of our culture, physically internalizing its principles and values. Hence, when Brahmins partake of their vegetarian meals, they express their commitment to the sanctity of life and to the principle of nonviolence; equally, when Argentinian gauchos bite into their bloody steaks, they reaffirm their masculinity and the violent vitality that distinguishes their lifestyle.

Yet it is precisely the nature of food as a constant and necessary part of life, consumed habitually and often nonreflexively, that consigns the culinary sphere to banality, unworthy of sustained scholarly attention. Anthropologists tend to give far more weight to substantial aspects of culture, such as kinship, religion, or language, and mention foodways only as a secondary phenomenon. If overlooking the importance of food seems to be rather the norm in anthropology, when it comes to the anthropological study of Vietnam by foreign and local scholars alike, the neglect is almost complete: Huard and Durand (1954), Hickey (1964), Popkin (1979), Jamieson (1995), Kleinen (1999), Malarney (2002), Hardy (2005), Fjelstad and Nguyen (2006), and Taylor (2004, 2007), in their important ethnographies of Vietnam, rarely mention food practices and hardly ever suggest that they may be meaningful in themselves. Even Thomas (2004) and Carruthers (2004), who highlight the importance of food in Vietnamese culture, are mainly concerned with globalization and the diasporic dimensions of Vietnamese cuisine, and overlook daily food habits and their meanings. In this sense, Krowolski and Simon-Baruchs (1993) ethnography of domestic food and eating in Danang is a salient exception.

In this book I approach food and eating differently: focusing on the cultural and social dimensions of the culinary sphere in the small town of Hoi An and emphasizing the motivations and meanings of eating that transcend physiological needs or ecological constraints, I show that looking at foodways allows us to approach Vietnamese society and culture from a unique perspective. This, I demonstrate, is a powerful analytical lens that allows for new insights regarding the phenomenology of being Vietnamese.

As a culinary ethnography of Hoi An, a prosperous market town of some 30,000 people in Central Vietnam, this book describes the local foodways and analyzes their social and cultural features. Hence, Rice Talks is first and foremost intended as a significant contribution to the anthropology of Vietnam, addressing the dearth of studies on Vietnamese foodways and, in particular, the neglect of the complex culinary sphere of Hoi An, a town that has been involved in global trade and cultural exchange for centuries.

Rice Talks is also a theoretical project that seeks to understand the unique position and qualities of the culinary sphere as a cultural arena. As such, it goes beyond the conventional anthropological understanding of food and eating as reflections of other social and cultural phenomena by conceiving of the culinary sphere as an autonomous arena, where cultural production and social change are initiated and elaborated. I focus on the ways by which differing facets of identity such as gender, class, ethnicity, religious propensities, and even political orientations are constructed, maintained, negotiated, challenged, and changed within the culinary sphere.

The ethnographic data presented in this book result from an ongoing project that began in 1998. While my initial twelve months of fieldwork in 19992000 laid the foundations for this book, repeated shorter stays of two to three months each year since 2001 have allowed for a close tracking of the powerful processes of development and change that characterized life in Hoi An during this period, and which still continue. Though change is an essential feature of every society and culture, taking it into account has always been problematic in anthropology, as the anthropological moment, as extended as it might be, is limited and not many ethnographers have the privilege of returning time and again to the field.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992. i An. 2. FoodSocial aspectsVietnamH

i An. 2. FoodSocial aspectsVietnamH