Table of Contents

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO MY PARENTS

LYNN TENDLER BIGNELL

and SIDNEY PHILIP GILBERT

YOUR WORDS AND ACTIONS CONTINUE

TO GUIDE AND INSPIRE ME.

I LOVE YOU.

A portion of the proceeds from the sale of this book will be donated to:

The Ovarian Cancer Research Fund, Inc. www.ocrf.organd The LUNGevity Foundation

www.lungevity.org

FOREWORD

by Kenneth J. Doka, PhD

WHEN I FIRST BEGAN to offer grief counseling thirty-five years ago, I expected to see widows and bereaved parents. Certainly, I thought, the loss of a lifelong mate or the loss of a child might tax the coping capacities of survivors and lead them to seek support and guidance. I was surprised that a third of my clients turned out to be adult children who had a parent or both parents die.

In retrospect, I should not have been so shocked. The death of a parent, even in adulthood, can be a severe loss. For many adults, it is our first significant lossthe first time we ever experience that roller coaster of grief. If these losses occur in adulthood, they come when we are relating to our parents differently. We begin to see them not as the awesome or awful people of our childhood, but as people like ourselvesstruggling, sometimes flawedand often we have a new appreciation for their role. It can seem unfair to lose them just as we are appreciating them, understanding them, or even caring for them. When the loss occurs when the bereaved is a child, the death can, indeed, define our lives.

The loss of a parent may even sharpen our awareness of our own mortality. There is a great gap between understanding that people die and internalizing the statement Someday I will die. As long as our parents are alive, we are buffered from the reality of death.

The death of a parent often creates a developmental push. When a parent dies, we may have to take on new responsibilities for the surviving parent, for other members of the family, or even for ourselves. When my father died, I realized that I would have to do the tedious work of reconciling my checkbook. He was a wizard with numbers, so whenever the checkbook did not balance, I would bring it to him. In both little and big things, we count on our parents. When one dies, we have to learn to count on ourselves.

When the second parent dies, things are even more complicated. Adult orphan seems like an oxymoron. In reality it is not. As long as parents are alive, no matter how old and successful we may be, we always know there is a place for uswith someone who has always cared. When our parents are gone, we are truly alone.

There are often other changes, as well. When both parents die, there is often a range of secondary losses. We may lose the family home. Holidays are different. Parents are often centering forces in the familybringing the siblings together for birthdays and other occasions; now the axis is gone.

Sibling relationships may change in the wake. Parents may have been the glue that kept siblings togetherthe lid that kept tensions from spilling over. In some families, issues over inheritances expose previous rifts, shattering a range of relationships and destroying the tenuous unity of the family.

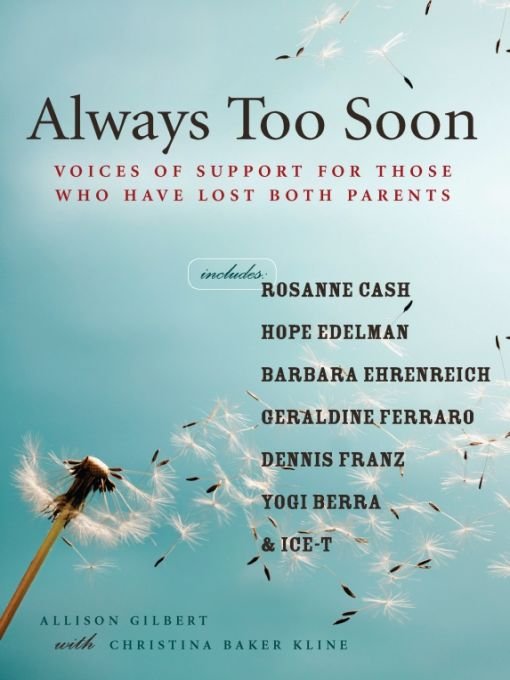

This is why Allison Gilberts book Always Too Soon: Voices of Support for Those Who Have Lost Both Parents is such a gift. There is value in the stories she has so carefully collected. First, they offer validation. Throughout the year, I speak all over North America about grief and loss. Most times I am lecturing to professionals about counseling individuals who are experiencing some aspect of loss. Often I do lectures for the general public. There the predominant question is a version of Am I going crazy? These questioners often recount normal experiences that we have as we grieveperhaps that up-and-down sense as we ricochet from one emotion of grief to another, or maybe the time it is taking to heal. In any case, we often, especially in our first experiences with grief, seem taken aback by the process. Hearing the stories of others reassures us that our feelings are shared. It answers the question Am I going crazy? with the quiet reaffirmation No, you are only grieving.

Second, these stories offer suggestions for coping. These can include areas such as how to manage family celebrations in the absence of someone we deeply loved, or more specific issues, such as who will sit in the chair that Dad normally sat in every Thanksgiving. As we read the pages ahead, we learn how others solved these same issueslarge and small. This gives us ideas and thoughts that we can apply to our own struggles.

We do that, however, through the prism of our own self. Grief is a highly individual process, so the best way to absorb these stories is to ask ourselves how we can apply the experiences of others to our own life and circumstances. Their choices may help inform our choices.

The strengths of these subjects may also remind us of our strengths. Look at what helped themfaith, friends, family. What will help us as we cope with the deaths of our parents?

Finally, these stories offer us hope. However horrendous the loss, however difficult the journey, the contributors in this book persevered. Their struggles inspire us. More than that, they promise that even in the midst of grievous loss, we can, do, and will survive.

KENNETH J. DOKA, PHD

Dr. Kenneth J. Doka is a professor of gerontology at the Graduate School of The College of New Rochelle and senior consultant to the Hospice Foundation of America. Dr. Dokas books include Living with Grief: Ethical Dilemmas at the End of Life; Living with Grief: Who We Are, How We Grieve; and Men Dont Cry, Women Do: Transcending Gender Stereotypes of Grief, among many others. He has published more than sixty articles and book chapters. Dr. Doka is also editor of the professional grief journal Omega and the monthly newsletter Journeys, published by HFA.

You may visit Dr. Kenneth J. Doka at www.drkendoka.com.

NOTE

a special note from grief counselor Lois F. Akner, CSW

IT WOULD BE SIMPLER if there were one way to experience grief. Then it would follow that there would be one way to get through it, one thing that would help us all. Alas, that is hardly the case. Grief is at once universal and unique. And as is evidenced by the stories in this book, we each experience it through a filter that is made up of our own history, the relationship with the person who died, the circumstances of the death, our resourcesboth internal and externalour beliefs, and our culture.

For more than two decades I have run a workshop, Losing a Parent Is Hard at Any Age, at the 92nd Street Y, a large cultural institution in New York City that serves the community, from babies to seniors and everyone in between. The workshop began when the Y took notice that there were not many places adult children could go to talk about this particular loss. Because the loss of a parent is virtually inevitable, people wrongly assume that it also means we are always prepared for it.

In the years I have been running these groups, I have learned that some people come through the doors wanting to speak; a few just want to listen. Most people want to hear from others, to feel less alone and to normalize what they are going through. It is through telling our stories that we acknowledge that something important happened and that we want help making sense of it.