Justin Walker 2015

Justin Walker has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

ISBN: 978-1-483-54686-5

Cover design by Caroline Shave.

List of Maps

Map 01: Chilean Patagonia (Northern Parts)

Prologue: The South

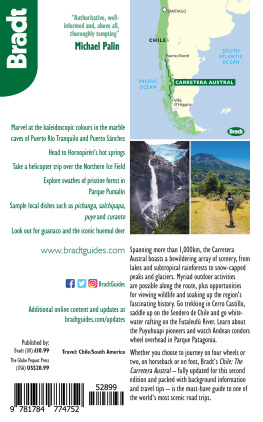

Stretched along the western face of South America, there lies an intriguingly shaped land. Surprisingly long and unusually narrow, Chile is unmistakable. She is a bamboo cane; a drainpipe. If she joined a fidgeting queue of nervously excited aspiring fashion models, bulbous Brazil and pot-bellied Bolivia would steal envious glances at Chiles sleek and slender figure. From head to toe, her skinny form extends an extraordinary 4300 kilometres, similar to the separation of London from the North Pole. Measured along the road, rather than in a straight line, the distance is even greater. The capital, Santiago, is a 2000-kilometre drive from northerly Arica and 3000 from Punta Arenas, the largest of the scattered settlements that cling to mainland Americas tapering tail.

Beyond Punta Arenas is a remote headland known as Cape Froward, principally noteworthy for its location at the very tip of the tail. Despite that accolade, this inaccessible spot is not the southernmost point of Chile. In fact, its not even close. Across the Strait of Magellan cluster hundreds of inhospitable islands in an intricate, tangled web of fjords and sea canals. Among the jigsaw pieces are familiar names: Dawson Island, the Beagle Channel and the archipelago of Tierra del Fuego whose ultimate, defiant outcrop, where the Hermite Islands finally cede to the Drake Passage, is Cape Horn. Even the Cabo de Hornos, which maintains an expressionless vigil over volatile churning waters long the subject of sailors nightmares, is not the endpoint. Beyond the horizon the Diego Ramrez archipelago, the final smattering of land in South America, breaks the surface of the angry ocean.

As far as my friends were concerned, their country projected further still. Maps invariably inset a diagram showing the Chilean Antarctic claim, a 37-degree slice of the icy continent that inconveniently overlaps with the sectors claimed by Argentina and the United Kingdom. Chilean Antarctic Territory also includes the Antarctic Peninsula and the South Shetland Islands. Given their less aggressive latitude, both of these have been selected by numerous countries for their Antarctic research stations, and they consequently rank among the more thoroughly explored parts of the continent. Whenever the topic arose, colleagues spared no trouble in eliminating any doubt I might carelessly have expressed: Chilean entitlement to that frozen land was an accepted fact, not a point for discussion. Accordingly, the mid-point of Chile is marked by a monument at Puerto Hambre, a small Patagonian bay that lies 4000 kilometres from Visviri in the northern desert and 4000 from the South Pole. Which, as everybody knows, is in Chile.

Once Id arrived to live in Santiago, not long passed before the high regard in which my neighbours and colleagues held The South became apparent. It is precioso, stunning, I was constantly told. Consequently, as evenings lengthened in the latter part of that inaugural year, I spent hours poring over maps of southern Chile, my deliberations aided by a glass or two of vino tinto. The outcome was a ticket to Punta Arenas, the most southerly destination within range of a domestic flight. When the school year lurched to a close in December, amid award ceremonies, balmy summer evenings and exhaustion, I took my trip to The South. I ate fire-roasted Patagonian lamb, lodged in a pink-painted clapboard house, and slept under canvas around the renowned W-circuit of the Torres del Paine National Park, losing in the process the first and finest of several cameras that disappeared throughout my South American years. These were places that few Chileans visited, I learned, since many lacked the means or opportunity or inclination to do so.

For a novice, it was a commendable first foray into Chilean Patagonia. Proudly returning to Santiago, brimming with tales of fearless endeavour, I was perplexed to discover that I hadnt visited The South at all. No, whered Id gone was so far off the map that it didnt count. The South for everyone else meant the regions of Los Ros and Los Lagos, much closer to the capital but still several hundred kilometres away and, crucially, within a committed days drive for the procession of chunky four-wheel-drive BMWs that head for rural refuge with the advent of summer.

From roaring waterfalls to belching sea lions, and from rolling hills to towering volcanoes, these are indeed enchanting regions. Eight sizeable lakes line up in a north-south row, like rungs on a ladder, with tongue-twisting names: Panguipulli, Riihue, Puyehue and Llanquihue. On their shores, smart holiday residences jostle for north-facing aspects. Towards the mountains, there are magical forests of monkey puzzle. Further south is the unenticing port of Puerto Montt, the most populous city in the region. And southwest of there is Chilo, Chiles largest island, known for its wooden churches, houses on stilts, colonies of penguins and a local cuisine known as curanto, still today cooked in a hole in the ground.

In contrast, the North of Chile is dominated by the vast, open expanse of the Atacama Desert, a place so dry that abandoned mining communities stand like ghost towns in the sand, having decomposed hardly at all in 50 years of disuse. Here in the desert, world-class observatories take advantage of constant clear skies, and in spite of plummeting night temperatures, the naked mountains never see snow. The church at San Pedro has a ceiling supported on beams of cactus wood, and El Tatio has the worlds highest geyser field. In the Elqui Valley, a local grape brandy is distilled, a potent spirit known as pisco. Tiny Pica is a sleepy oasis awash with lemon groves, and when spring conditions conspire favourably around coastal Caldera, there are glimpses of the desierto florido: the flowering desert.

The eastern margin of Chile is formed by the ubiquitous barrier of the majestic Andes. In winter, the dreamy view of snowy peaks was a constant distraction outside my office window. The Cajn de Maipo is a spectacular Andean canyon within easy reach of the capital, and the upper mountains are close enough for a day trip to hike, to ride or to ski. High in the cordillera, there is a cross-border route known as Paso Los Libertadores, frequently closed by snowfall. On the Argentine side, the road to Mendoza gently descends through striking scenery of rusty red rock, complemented in autumn by amber-leaved poplar: elongated arrowheads pointing to the sky.

Out west are the winelands. Beyond the interminable vineyards and over a second mountain range is the Pacific coast. Every family has its favourite bay or resort, and the lucky ones keep an apartment there: a weekend bolthole and a summer sanctuary to escape the citys roasting heat. Some way offshore is the Juan Fernndez archipelago, known for its harvest of rock lobster. Three thousand kilometres further west is Rapa Nui, annexed by Chile in 1888 and also known as

Next page