Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

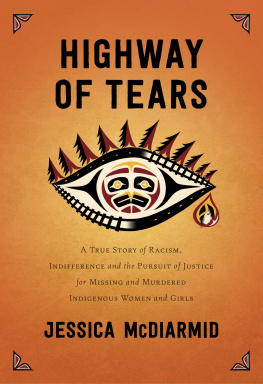

Copyright 2019 Jessica McDiarmid

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written consent of the publisheror in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing agencyis an infringement of the copyright law.

Doubleday Canada and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House Canada Limited.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Highway of Tears / Jessica McDiarmid.

Names: McDiarmid, Jessica, author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190051140 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190051361 |

ISBN 9780385687577 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780385687584 (EPUB)

Subjects: CSH: Native womenCrimes againstBritish Columbia, Northern. | Native womenViolence againstBritish Columbia, Northern. | LCSH: Missing personsBritish Columbia, Northern. | LCSH: Murder victimsBritish Columbia,

Northern. | LCSH: CanadaRace relations. | CSH: Native womenBritish Columbia, NorthernSocial conditions.

Classification: LCC HV6250.4.W65 M33 2019 | DDC 362.88089/97071185dc23

Book and cover design by Five Seventeen

Cover illustration by Kym Gouchie

Cover texture: wildtextures.com

Published in Canada by Doubleday Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

v5.3.2

a

For the women and girls who

never came home, and for their families

FOREWORD

BECAUSE I AM AN INDIGENOUS WOMAN , I am six times more likely to be murdered than my non-Indigenous sister. I am considered high risk just by virtue of being Indigenous and female. This is my reality. I am a statistic. Jessica McDiarmids book brings life and a face to the statistics. The girls and women whose stories are presented in the book were someones daughter, sister, mother, aunt, grandmother, friend, etc., and they were loved and important. They are still loved and important, but now they are also missed.

Over many years, I have worked locally, regionally, nationally and internationally to raise awareness of the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada. I have done so because this issue is personal: my first cousin, a most treasured young woman, was lost along Highway 16 in British Columbia. Ramona Wilson went missing in 1994 and her remains were found a year later. Ramona was not only beautiful, she was smart, tenacious and had an effervescent personalityshe was going places. She was loved. The pride my Aunty Matilda and her siblings felt for her radiates from them every time they speak about her. The abrupt end of her life at the tender age of sixteen left an indelible mark on the heart of our family.

This book is a timely reminder that those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Jessica paints a clear picture of the political and social climate in which many young women went missing along Highway 16. It was a time of political unrest due to the perceived threat of losses to jobs, properties and resources that would result from treaties with First Nations governments. There was an influx of workers into the resource sector, increasing the number of male-dominated camps. There was a lack of transportation options and a lack of essential health, social and education services.

In the north today we are facing the same factors that leave Indigenous women and girls vulnerable. There is friction between Indigenous and non-Indigenous northerners due to conflicting opinions on resource extraction. The planned liquefied natural gas plant in Kitimat and other resource extraction projects will see an increase in work camps, and the lack of services and access to those services is ongoing. Although a transportation plan developed for northern British Columbia has provided limited bus services along the Highway 16 corridor, Greyhound no longer offers bus service in the province.

In 2006, Carrier Sekani Family Services and Lheidli Tenneh hosted the Highway of Tears Symposium for approximately 700 participants. It was the start of a collaborative effort between every level of government, Indigenous communities and families of the victims, and service providers to meet, engage and discuss. The Symposium yielded a report with thirty-three recommendations toward solutions to the systemic, historic and ongoing problems confronted by people living along the highway. From those recommendations, the Highway of Tears governing body, composed of family members of the victims, government and service organizations representatives, was established and the Highway of Tears (HOT) initiative was born. The HOT initiative would coordinate and oversee the implementation of the HOT recommendations. It was my honour to chair the HOT governing body and guide the work of the initiative through the Carrier Sekani Family Services.

When Jessica approached me about her desire to write a book on the Highway of Tears, I brought forward her request to the governing body, which supported and endorsed her work. After her years working in Africa for human rights and writing for the Toronto Star, Jessica returned home to the north to provide her in-depth perspective on the Highway of Tears. Jessica has put her blood, sweat and tears into this book, evident by her countless hours of research and interviews. Truly, she has given justice to a very sensitive and complex issue.

I am thankful that Jessica has so succinctly and thoroughly documented the history of the Highway of Tears and that the stories of our girls and women will never be forgotten. I am thankful that the work, energy and spirit that has gone into raising awareness of our missing and murdered girls and women is captured in the telling of our story. In Jessicas words, Ramona has been here all these years: in the courage in her mothers eyes, the strength in her sisters voice, in all the work theyve done. We have much work still to do.

This book is a tribute to all our warriors who demand justice for those who no longer have a voice. Through her words, Jessica McDiarmid has lent her voice in the fight for justice for those we can no longer hear. In the telling of the story of the Highway of Tears, Jessica has become one of us warriors. For this, my family will be forever grateful.

Mary Teegee

Maaxsw Gibuu (White Wolf)

Executive Director,

Child and Family Services,

Carrier Sekani Family Servcies

Chair, B.C. Delegated Indigenous Agencies

President, B.C. Aboriginal Childcare Society

INTRODUCTION

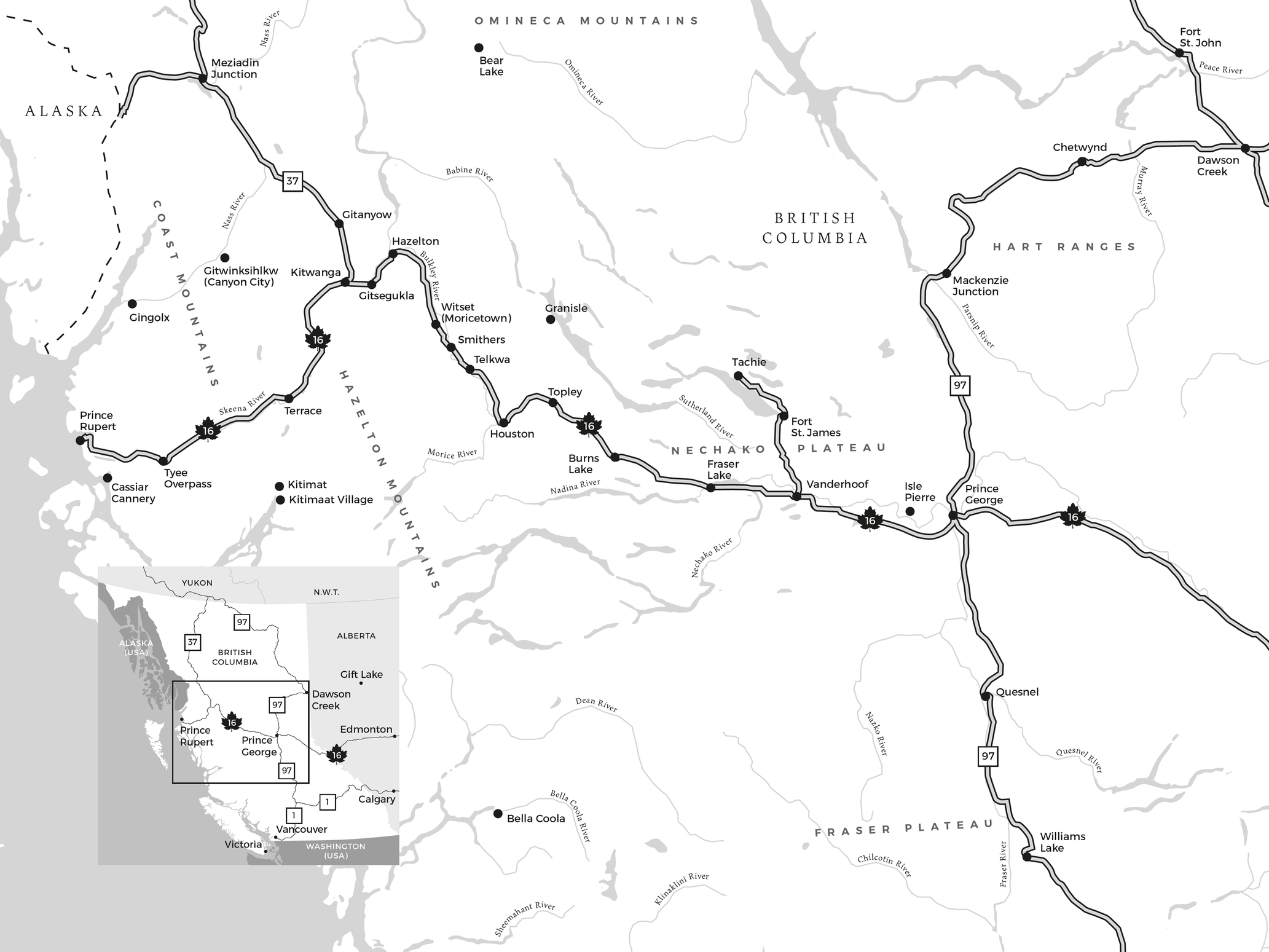

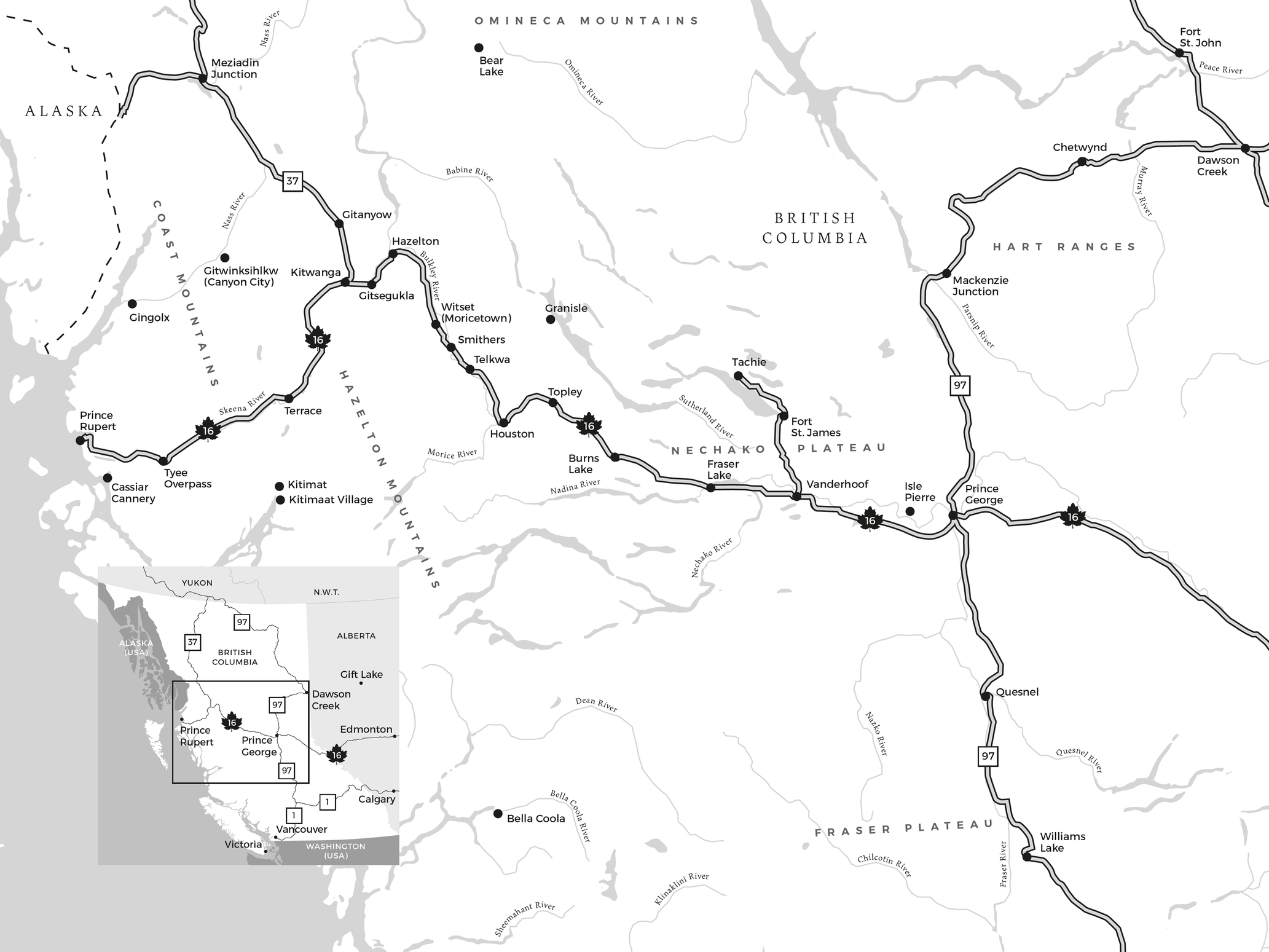

THE HIGHWAY OF TEARS

THE HIGHWAY OF TEARS is a lonesome road that runs across a lonesome land. This dark slab of asphalt cuts a narrow path through the vast wilderness of the place, where struggling hayfields melt into dark pine forests, and the rolling fields of the Interior careen into jagged coastal mountains. Its sparsely populated, with many kilometres separating the small towns strung along it, communities forever grappling with the booms and busts of the industries that sustain them. At night, many minutes may pass between vehicles, mostly tractor-trailers on long-haul voyages between the coast and some place farther south. And there is the train that passes in the night, late, its whistle echoing through the valleys long after it is gone.