In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

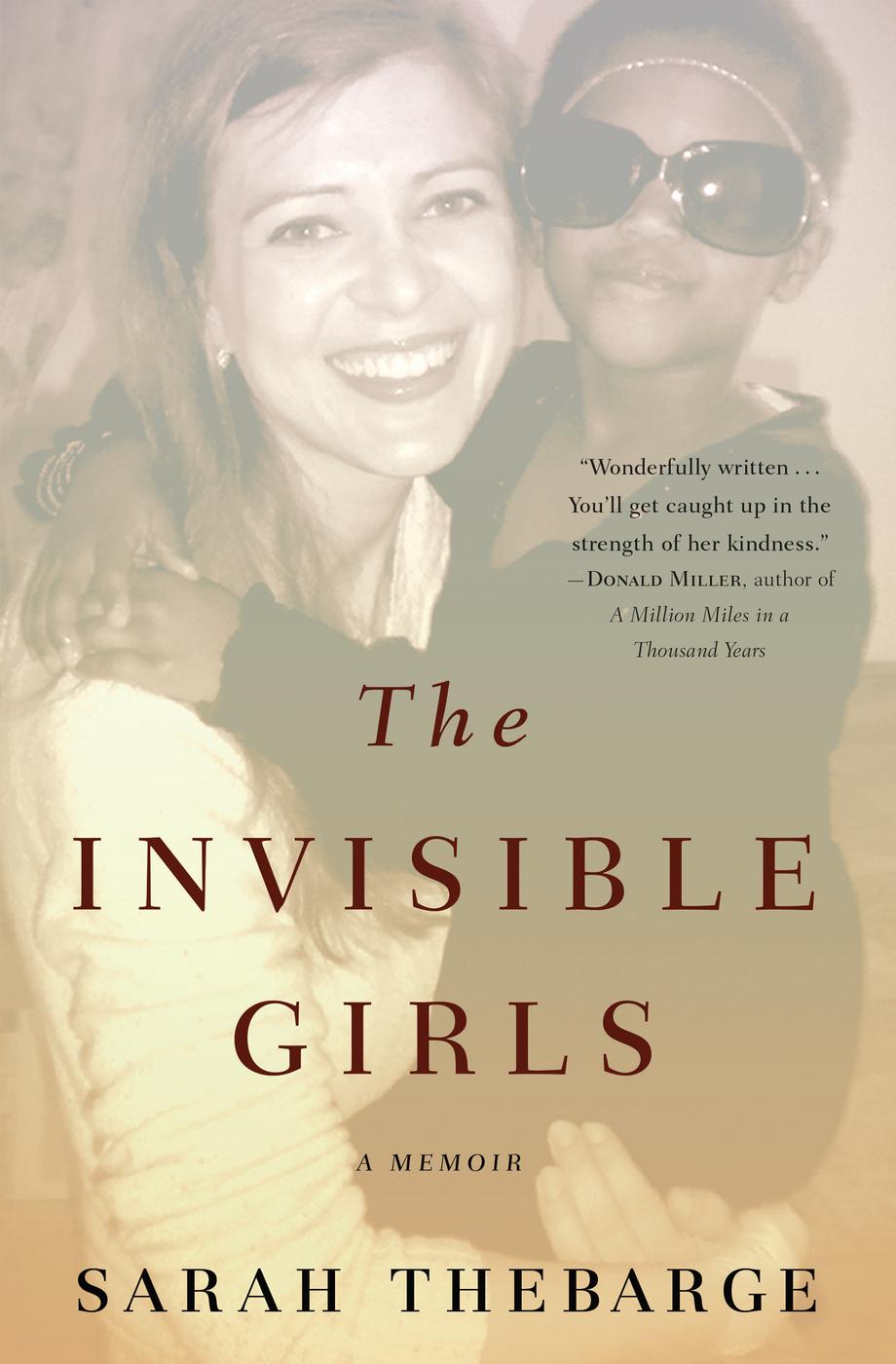

For the Invisible Girls.

All of them.

I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.

Ralph Ellison

O NE YEAR AGO , I was riding the train from the Portland suburbs toward downtown on a sunny fall afternoon when a pair of sparkling brown eyes peeked around the corner of my book, and then quickly disappeared. A minute later, the eyes appeared for a second, and then disappeared again, and I realized the little girl sitting across the aisle was playing peekaboo with me.

I lowered my book a few inches and winked at her. She tried to wink back, but she was preschool age and didnt have the fine motor skills to copy me, so instead she scrunched up both eyes in a prolonged blink.

As she contorted her face, trying to figure out how to wink, I saw that her small frame was covered with baggy sweatpants and a mismatched knee-length print dress, and she was wearing cracked sneakers with frayed laces. Her silky brown skin and bright eyes stood out against the bedraggled backdrop of her clothes, and I found myself captivated by the contrast.

Her mom, who wore a yellow, orange, and red print African dress and a matching headscarf, sat with her head resting on the window, staring blankly at the freeway that paralleled the train tracks. She was short and stout and her skin was wrinkle-free, but her shoulders drooped and her brow was furrowed, making it difficult to guess her age. She could just as well have been twenty-five as forty-five.

A toddler, who wore threadbare pants, an oversized dress, and old sneakers, was standing between the mothers parted knees, trying to sleep while standing up. I watched this child, with her shorn head and chubby cheeks, as she grasped her mothers skirt, trying to stay upright and sleep at the same time. I was thinking, Someone needs to hold that tired little girl, when she opened her sleepy eyes and looked up at me. I held out my arms. She climbed into my lap, and less than a minute later she was fast asleep with her head against my chest.

The scene unfolded so quickly, I hadnt had time to ask her mother if it was okay. Now that the toddler was sleeping in my lap, I looked at the mother for permission, hoping she didnt disapprove of a strange woman holding her daughter. Without moving her head from the windowpane, her eyes followed my voice until they rested on my face.

Its okay? I asked her.

She looked at her sleeping daughter and flashed a weary smile. Yah, she said. No problem.

Your daughters are precious, I said.

Yah? she asked tentatively.

I nodded. Absolutely.

She smiled again. Tank you. Tank you.

Wheres home for you? I asked.

She didnt understand, so I tried again. Where are you from?

Somalia, she said.

Do you have other children? I asked.

She held up three fingers. In school, she said.

Wow, five children! Is there someone at home to help you?

She shook her head. Her English was limited, so with short phrases and hand motions she explained she and her husband had come from Somalia with their five children, but her husband had left them soon after they arrived.

When she couldnt find the words to tell me more details of her story, she just shook her head, and her shoulders seemed to droop more, bowed low by an invisible weight. Its too much, she said, repeating her words for emphasis. Its too much. And then she sighed, and resumed her contemplation of the passing scenery in silence.

After a few unsuccessful attempts at winking, the four-year-old gave up her efforts. When she saw her sister was sleeping and her mother was looking away, she climbed down from her seat, walked across the aisle, and wiggled herself up until she was perched next to me on the edge of the narrow seat. She took two dice out of her pocket, placed them in my palm, and closed my fingers around them. She looked up at me, her wide eyes sparkling with anticipation.

My game, she said. This my game. Then she tried to pry my fingers away from the dice, laughing, while I pretended my hand was an unyielding claw.

As I played along with the game this little Somali girl had invented, I started to worry about the family. I thought about how overwhelmed Id be if I were abandoned in a country ten thousand miles from home, left to care for five children by myself with no language training and no money. How would I even begin to navigate a culture that was so different from anything Id known?

And then I thought about the Golden Rule: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. If the situation were reversed and I were a single mom in Somalia and a kind stranger saw me on the train, what would I want her to do? Help me, I decided. I would want her to help me.

When the mother looked my way again, I took a notepad and pen out of my messenger bag, and asked, Where do you live? As soon as the question left my lips, I was relieved Id had the courage to ask so I could check on them later that week. But I also felt a small twinge of fear that Id scared this poor woman, who probably already felt vulnerable.

Without saying a word, she pulled a crumpled envelope with a handwritten address from the waistband of her skirt and handed it to me. I copied the address and gave the envelope back to her.

Thank you, I said.

As we approached the next station, the woman woke up the three-year-old and took her and her sister by the hand. At the next stop, they swept off the train.

As the doors closed, I saw them standing at the corner, waiting to cross the street. The four-year-old was looking back, waving at me. And as the train pulled away from the station, I realized her dice were still tucked snugly in the palm of my hand.

T WO YEARS BEFORE I met the Somali family, I had escaped from New Haven, Connecticut, to Portland, Oregon. I was fleeing eighteen months of breast cancer treatments that left me physically, financially, and spiritually depleted.

At the end of a grueling course of treatment, which included five surgeries, six months of chemotherapy, and thirty sessions of radiation, I was hospitalized with pneumonia and sepsis. At twenty-eight years old, I lay in a hospital bed for nearly a month, wondering if I was going to live or die. Even the hospital staff didnt hold out much hope for me.

When I went to the ER in sepsis, the resident asked if I wanted to be resuscitated if I coded, implying that because I had cancer, my life might not be worth saving. He even randomly ordered a CAT scan of my brain, saying, You might have brain metastases we dont know about.

When I had a chest X-ray a few days later, the tech said, Im so sorry to have to ask you this because the answer is obvious, but is there any chance you could be pregnant?

I didnt mind the question, but I was offended by the preface to her question. What was so obvious? Did she think I was automatically infertile because Id been through chemo? Or even worse, that no man in his right mind would sleep with me because of my disfigured chest? Or that I was already half-dead?