Contents

Guide

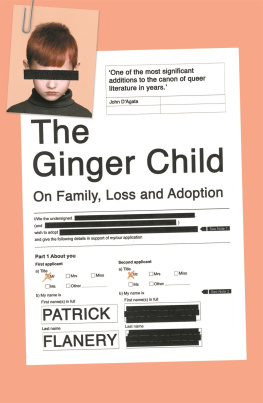

The Ginger Child

Also by Patrick Flanery:

Absolution

Fallen Land

I Am No One

Night for Day

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Patrick Flanery, 2019

The moral right of Patrick Flanery to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Interior: Monkeyboy Kate Gottgens, on is reproduced with kind permission of the artist

Hardback ISBN 978 1 78649 724 6

E-book ISBN 978 1 78649 725 3

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

ginger, n. and adj.

A. n.

1. a.

The rhizome of the plant Zingiber officinale, which has a distinctive aroma and hot spicy taste, and is used in cooking and as a medicinal agent.

B. adj.

c.

Of a person: having reddish-yellow or (light) orange-brown hair, and typically characterized by pale skin and freckles. Hence more generally: red-haired.

[Short for ginger beer. Cockney rhyming slang for queer.] (frequently derogatory and offensive). Homosexual.

*

ginger, adj. (and adv.)

Origin: Formed within English, by back-formation. Etymon: gingerly adv.

Cautious, careful; gentle Also: easily hurt or broken; sensitive, fragile.

Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, 2017

Names and other details have been changed out of respect for the privacy of certain individuals.

MOTHERS

T oday, many days, I play a private game, imagining hypothetical mothers. Not my own mother, who I know well. Not mothers who would bear a child, abandon it, relinquish it, or have it taken away, a child we would then adopt, but mothers who would bear a child for us, altruistically.

I look through profiles of friends and acquaintances on social media, think of possibilities, past promises.

When I see your picture with your husband and children, I remember how you and I pledged to have a child together if we were both still single at thirty-seven. I wonder if you ever think of that now.

At the time, when we were in our twenties, did you want me to say, lets have a child now, lets not wait? Although that was what I felt, I could not muster the courage to say it for fear you would laugh at me in your charming, heart-breaking way.

A couple of years ago, when we saw each other for the first time in more than a decade, it felt to me that not even five minutes had passed. Although we both now have husbands and you have children and another pregnancy would be a risk not worth taking just for the sake of a friends desire to have his own child, I cannot help imagining what might have been.

Today, of course, the idea tips us over into the fantastic. But I still think about it, what you having a child for me and my husband, what raising that child, what the closer bond created between us, would do to all of us, for the good.

But I do not expect.

You understand, I hope.

I see your picture, with your two children, your wife, and think about the processes you went through, different anonymous donors, speculating about which traits your children may have inherited from those unknowable men, the way the two girls are so wildly different in appearance and character, both of them dark-haired while you are blonde, as if your genes had left no visible trace on either of them. I think about your generous assertion, after giving birth to the first child, that if you were younger youd happily get pregnant for us but you could not conceive of a second pregnancy, the first was so difficult and you were getting old, your body could not take the further damage, the risk was so great. And then, a few years later, you decided to try again, for yourself and your wife, and were successful.

I look at you building a career, negotiating the frustrations of distant family and complexities of sibling relationships, doing it all with such an elegant determination to get things right, while worrying whether you will have the life you want in the end.

Does it ever occur to you that we could reach a mutually beneficial agreement that would give you something in exchange for the someone we so desire? Such wondering about your own wondering leaves me feeling poorer and meaner, uglier, because it should not be about money, any of this, but only about love.

You will undoubtedly have your own child or children, and why want the complication of another child, even a child not biologically yours but with that connection nonetheless, of having carried her or him in your body for nine months, a child who would appear before your own children as the first child, the child you relinquished because he or she was not yours to keep.

How would you explain that, if we did it?

And would it be so difficult to explain, in the end?

Would it require no more than saying, I had that child for them because I could? But she is not my child in the way that you are my children, you might say to your sons, your daughters, if that day ever came.

I pass you on the street as you are talking on your phone, saying, No, Kev, honestly, I got it. Dont you understand Im serious when I say I dont want a kid? What would happen if I waited for you, a stranger, to finish your conversation and then asked in the politest, least threatening way I could muster, But would you have a kid for us? Id pay you. Id pay you however much you want, even if I dont have it, even if the law wont let me, Ill give you whatever you think you need to make it worth your while, Ill rob banks to pay you, and I know, in that thinking, how deep my desperation has become.

It feels as if I spend whole days out in the world, on trains and trams and undergrounds, sniffing out fertility and sympathy and if not willingness then openness and radical politics and the selflessness such an act would require, to do this without paying scores of thousands of dollars to lawyers and clinics.

And yet I still imagine, you know, robbing a bank if thats what it takes.

(Not that I would.)

I meet you for the first time in fourteen years and although you are now, like me, in your early forties, you are single and unlikely ever to have a child of your own. Sitting across from you over coffee I think, why would it not be possible? I think this and at the same time I know: this will not happen.

Yet my brain oscillates between the wondering and the knowing, and when it does not oscillate, holding one in dominance over the other, it holds both the wondering and the knowing (this cannot be) at the same time, concurrent, living the cognitive dissonance of desire and despair.