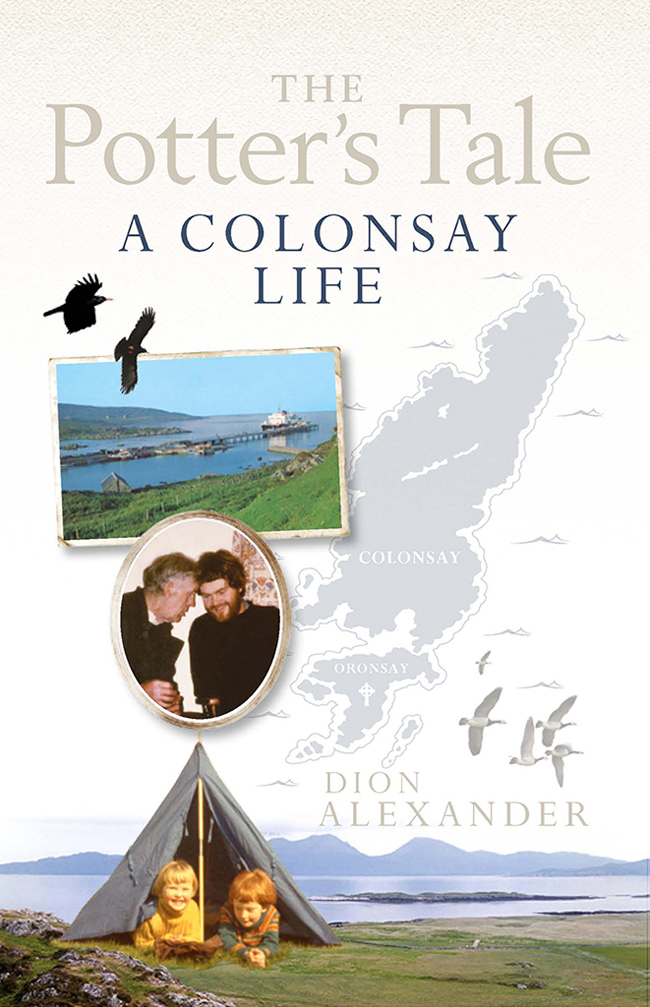

THE POTTERS TALE

First published in 2017 by Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Dion Alexander 2017

The right of Dion Alexander to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publishers.

ISBN: 978-1-78027-473-7

eISBN: 978-0-85790-945-9

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset in Bembo at Birlinn

Printed and bound by Grafica Veneta

www.graficaveneta.com

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am very grateful to all those who have encouraged and helped me in any way to bring this book to eventual fruition, not least Ian and Sandra MacAllister, Keith Rutherford, Irene Christie and Hugh Andrew and his hardworking team at Birlinn. I really dont deserve the wonderfully written and flattering foreword penned by one of my heroes, Jim Hunter but Ill take it, with huge respect and gratitude. I am particularly indebted to Carol and Peedie McNeill for their unwavering hospitality, kindness, support and general indulgence, aided and abetted on sea and land by David and Jan Binnie. Finally, my beloved other half, Helen, deserves a special mention for bearing with me throughout the books long gestation period.

Di Alexander, The Colonsay potter as was, October 2016.

DEDICATION

For all my loved ones

and

for anyone with a special place in their heart for the magical

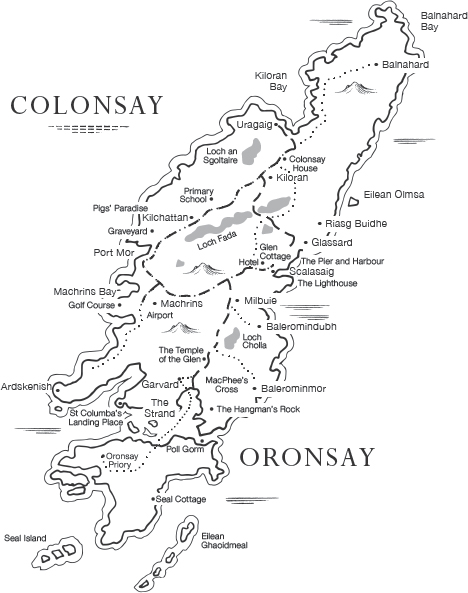

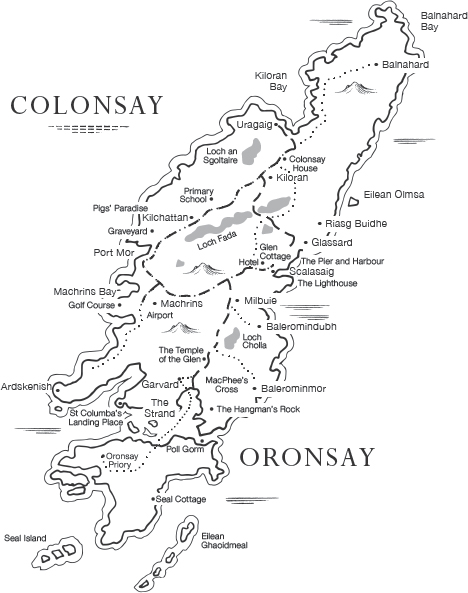

Hebridean islands of Colonsay and Oronsay

FOREWORD

by

James Hunter

T his book repays a debt the debt its author feels he owes to the Hebridean island of Colonsay where Di Alexander, his wife Jane and their baby son settled in 1972. Their being there was not untypical of the times. A number of young southerners, often of hippyish outlook and artistic bent, were then coming to the Highlands and Islands in search of the good life consisting usually of a mix of self-employment and self-sufficiency. Round every corner, we natives sometimes said, youd find a pottery, a potter and (frequently) a goat. Put like that, our take on these newcomers might seem cynically condescending. In part, no doubt, it was. But in my case anyway, other emotions were involved. I was of Dis age-group. But I was one of innumerable Highlanders whod headed elsewhere in search of a higher education and such job opportunities as it might open up. Eventually, in the 1980s, Id make it back to the Highlands and Islands. But ten or fifteen years earlier that seemed unlikely. Then I was very much a product of age-old Highland thinking (less prevalent now but by no means extinct) to the effect that anyone wanting to get on in the world had better begin by getting out. This, or so we were encouraged to believe, might be regrettable but it was also unavoidable. Hence the envy, or perhaps it was resentment, some of us felt on seeing other young folk, of whom Di and Jane were two, demonstrably giving the lie to the notion that the Highlands and Islands had nothing to offer by moving north, not south, and by setting up home in the very places so many of us were quitting.

At a couple of generations remove, Di is himself a product of our centuries-long Highland exodus his surname deriving from Caithness fish-curers and boat-builders who were among the beneficiaries of the Victorian herring boom that turned Wick into one of Europes busiest fishing ports. Just before 1900, one of those Alexanders, Dis paternal grandfather John, won a scholarship to Edinburgh University where he graduated in medicine prior to marrying and going off to work in West Africa. A Scottish connection would be re-established when Dis father, Donald, took up a university post in Dundee. But reinforcing this connection, Di stresses, was Dr John Alexanders decision, on retiring from the south of England practice hed acquired on returning from Africa, to set up home with his wife Hilda at Weem near Aberfeldy. There Di holidayed occasionally with his grandparents, and there he began, he says, to feel the urge (acted on as described in his opening chapters) to make a life for himself in the Highlands and Islands.

I didnt know Di then. That would change when I went to Skye to work for the Scottish Crofters Union, now the Scottish Crofting Federation. This was in the mid-1980s when Margaret Thatchers ministers, or so it was feared, might be tempted to axe the taxpayer-financed Crofter Housing Grant and Loan Scheme which advanced to crofters a part of the cash it took to get new homes built on crofts. How, we wondered, might we best make a case for the schemes retention? What we needed, I knew, was expert advice on housing policy, and it was in this connection I first heard mention of Di Alexander. Initially, I envisaged someone female. Then, when Id been put right on Dis gender, I thought he must be Welsh. In fact Di, who grew up in Berkshire and Wiltshire, owes his first name to parental fascination with classical Greece. Which is not, by the way, to suggest that Donald and Budge Alexander were more engaged with the distant past than with what was going on around them Donalds still widely shown film footage of the impact of the 1930s depression on South Wales miners being a pointer to his having had much the same commitment to social justice as is evident in his sons endeavours on behalf of a whole host of Highlands and Islands communities.

When Di became one of the people who helped the SCU secure the continuation of the Crofter Housing Scheme (which, we demonstrated to initially sceptical Tory politicians, was a highly cost-effective means of enabling families to become home-owners), he was working for Shelter. Afterwards he became a key figure in, first, the Lochaber Housing Association and, then, the Highlands Small Communities Housing Trust. Between them, these organisations have provided and are still providing hundreds of new and affordable homes in localities where such homes would otherwise have been lacking. This achievement, Di stresses, is by no means his alone. Thats true. Hes had lots of hard-working collaborators. But Dis contribution has been huge all the same not least because of his having developed all sorts of insights into the crucial connections between housing provision and wider well-being. A place where there are houses to buy at reasonable prices, or where young folk in particular can afford to rent, is a place that can flourish and grow. A place lacking these things, as all too many Highlands and Islands communities know to their cost, is doomed to economic contraction, population loss, stagnation and decline.

Dis understanding of those issues, together with his longstanding determination to do something about them, he attributes (as is evident on following pages) to his years in Colonsay. This, then, is his thank-you to islanders who both received him and his family very warmly and who, though this would take time to become apparent, did much to shape Dis life, his outlook, his philosophy. And not just his.

Between 2010 and 2015 the First Secretary of the Treasury in Britains then government, a Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, expended a great deal of energy and political capital on winning a fuel-duty discount for those Hebridean and Highland communities where the effects of distance and disadvantage are constantly aggravated by fuel costs far higher than those prevailing in urban localities. First Secretaries of the Treasury do not generally bother themselves greatly with such matters. That this one did stemmed from his upbringing. At one point in this book he features as a little boy adding to the stresses and strains surrounding his younger sisters premature arrival in a Colonsay cottage by getting himself into the cottages chimney and coating himself from head to toe with soot.