Silver Rights

Constance Curry

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

MARIAN WRIGHT EDELMAN

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Published by

Algonquin Books

of Chapel Hill

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

Workman Publishing

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

1995 by Constance Curry. All rights reserved. Introduction by Marian Wright Edelman 1995 by Marian Wright Edelman.

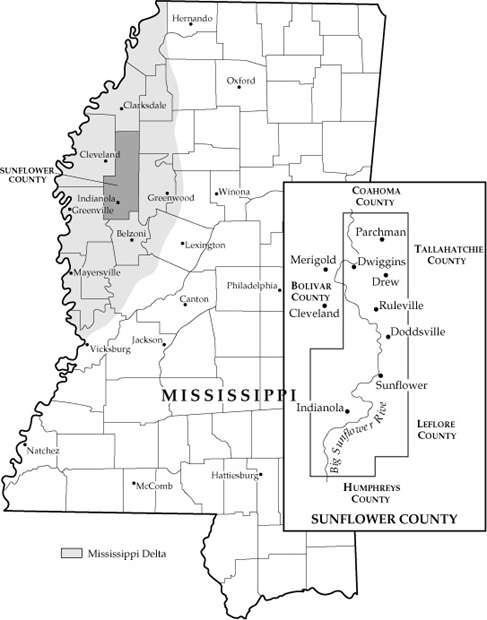

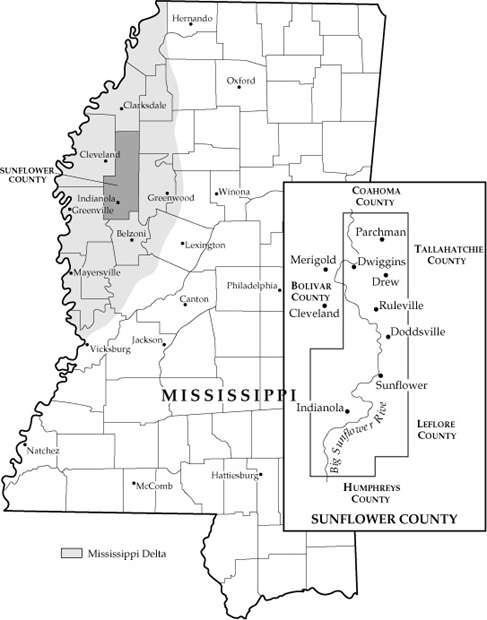

Title page photograph: Pemble Plantation, 1965. Map appearing on page x illustrated by Bill Nelson.

Abraham, Martin and John by Richard Holler. 1968, 1970 Regent Music Corporation. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

E-book ISBN 978-1-56512-831-6

To the unsung heroes of the 1960s Civil

Rights Movement who risked their lives and

livelihoods to secure a better education for their

children, and to the memory of my parents,

Hazle and Ernest Curry.

Although I value the Civil Rights Movement deeply, I have never liked the term itself. It has no music, it has no poetry. It makes one think of bureaucrats rather than of sweaty faces, eyes bright and big for Freedom!, marching feet.... Older black country people did their best to instill what accurate poetry they could into this essentially white civil servants term... so that what one heard was Silver.

Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers Gardens

Contents

Introduction

Mississippi... 1965. Thats all you need to say to conjure up a portrait of the incredible individual struggles that made up a movement that forever changed our country. Many of those struggles are a part of history now, to be read and, I hope, appreciated by generations to come. Many of those individual struggles will never make it into our history books, but they are a part of our history nevertheless. I am grateful that one of my heroines has had her story brought to a wider audience by a wonderful author who was there to watch it unfold. Constance Curry was a member of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) and did all she could to help the Carter family in those years. Thank God for her, and for the Carters, and for those like them.

Mae Bertha and Matthew Carter and their family endured a terrifying nightmare to educate their children. They were the first (and only, for several years) black citizens in Sunflower County to sign Mississippis freedom of choice papers, sending their children to previously all-white schools.

According to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Mississippi had to find a way to integrate its schools. Freedom of choice papers, to be signed by parents designating the schools their children would attend, were Mississippis answer to avoiding desegregation. The white establishment knew black citizens could be intimidated and threatened and, one way or another, prevented from enrolling their children in the white schools.

Miss Mae Bertha and her family proved them wrong, just like the other brave band of parents who had dared challenge school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education to give their children a better future.

In June 1967, as an attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, I brought suit for Mae Bertha Carter on behalf of seven of her children, Larry, Stanley, Gloria, Pearl, Beverly, Deborah, and Carl, against the Drew, Mississippi, Municipal Separate School District in U.S. District Court. In that suit we stated that the fear of white retaliation, firmly grounded in fact, has deterred other Negroes from choosing the formerly white schools pursuant to the districts freedom of choice plan. The class-action suit asked for injunctive relief against the segregated and discriminatory system that placed a cruel and intolerable burden upon black parents and students. We won. The court decision came down in 1969 throwing out freedom of choice plans and ordering desegregation of the schools. That could not have happened without the Carters.

Miss Mae Bertha and her husband Matthew joined the NAACP in 1955, slipping quietly into secret meetings in the churches. It was a dangerous thing to be a member of the NAACP in Mississippi in 1955. In the sixties and seventies she and her family spoke out and marched. Two Carter daughters were arrested for marching for voting rights. Miss Mae Bertha and Matthew were part of the 1 percent of the black population in Mississippi who registered to vote when the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965.

This deeply moving book chronicles the pain and poverty in the lives of sharecroppers, their extraordinary grit, courage, and endurance. Miss Mae Berthas children had listened to their great-grandmother tell stories of being a slave and to their grandmother talk of freezing winters without wood and nothing but last summers dried vegetables to eat. The older Carter children spent backbreaking days picking cotton, went to poor all-black schools that operated only part of the school year, shared old school buses, old books, and precious few supplies. All-black schools of the time were sometimes taught by teachers who had limited educations themselves. When the opportunity came for the eight younger Carter children to go to better schools, the Carters stood united, children and parents, in their determination to ensure a better future, no matter what the cost. Miss Mae Bertha said that changing schools was the chance to get the children out of the cotton fields. The whole family felt that it was the right thing to do. The older children signed their own freedom of choice papers and Miss Mae Bertha signed for the younger ones.

Every day Miss Mae Bertha struggled to maintain her courage, commitment, and perseverance to achieve and obtain what was right for herself and her children. She never lost sight of the goal: getting the best education possible for her children.

Equally as important, her work didnt stop with her own children. After taking a job with Head Start and working with young children, she continued to work on school desegregation and the second generation of problems resulting from school desegregationdisproportionate suspensions of black male students, different conduct rules for black students (including a demerit system that included sneezing as an offense), and overinclusion in special education programs.

In 1969, Miss Mae Bertha traveled with other civil rights activists to Washington, D.C., on a trip sponsored by the AFSC. They went to see then-Attorney General John Mitchell and occupied his office when he refused to see them. There, as always, her message was clear and powerfulshe was there as a black mother who wanted the best for her children. She was not talking about why blacks should go to school with whites; she knew access to a better education and a better life for her children was the prize. The attorney general finally relented and saw them, but she was ready to go to jail if necessary for her principles and her right to be heard.

She continued her voter registration work and later helped form and became president of the Drew Improvement Association. She worked with parents and children in the town to keep up the pressure and the interest in better education for all children. She has served as a vice president of the NAACP and her daughter Beverly has served on the formerly all-white school board that so resisted the Carter childrens enrollment years ago.

Next page