PRAISE FOR THE LAST WILDERNESS

A history of the Olympic Peninsula, it tells the story of pioneersthe farmers and loggers, fishermen and businessmen who tackled the ruggedly beautiful country and made their livings on it. It does for the peninsula what Morgans Skid Road did for Seattle, portraying its history for natives and newcomers to appreciate and enjoy.Seattle Times

It is good history and packed with outrageous anecdotes and uproarious humor, it is marvelously well-written. Here is the story of the Olympic Peninsula and its environs, the saga of the opportunists and the dreamers, the lumbermen and the would-be-farmers... the final failure of the utopian settlement at Home, and the fight to save at least part of the rain forest as a national park.Pacific Historian

So good a book as this will inevitably bring many new visitors.... Those who have read this book will have an excellent knowledge of an historical background that is probably as fascinating as that of any other region, West or East.New York Herald Tribune

Rollicking Americana, with useful statistics about Congressional actions to preserve this remarkable area.Kirkus

MURRAY MORGAN

Introduction by Tim McNulty

THE LAST

WILDERNESS

A HISTORY OF THE

OLYMPIC PENINSULA

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS Seattle

Copyright 1955, 2019 by Murray Morgan

Introduction to the 2019 edition copyright 2019 by the University of Washington Press

First paperback edition published in 1976 by the University of Washington Press Original cloth edition published in 1955 by Viking Press and Macmillan Company of Canada Ltd.

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Design by Thomas Eykemans

Composed in Adobe Garamond Pro, typeface designed by Robert Slimbach

23 22 21 20 195 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

www.washington.edu/uwpress

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA ON FILE

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018054733

The last chapter appeared in part in the Saturday Evening Post under the title Loneliest Spot in America.

COVER IMAGE: Postcard, view north from James Island, Washington, 1907.

University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, WAS1394.

FRONTISPIECE: Bucker crosscutting seven-foot spruce, n.d. Finishing strokes were made from beneath, with saw upside-down. Photograph by Darius Kinsey. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, D. Kinsey A47.

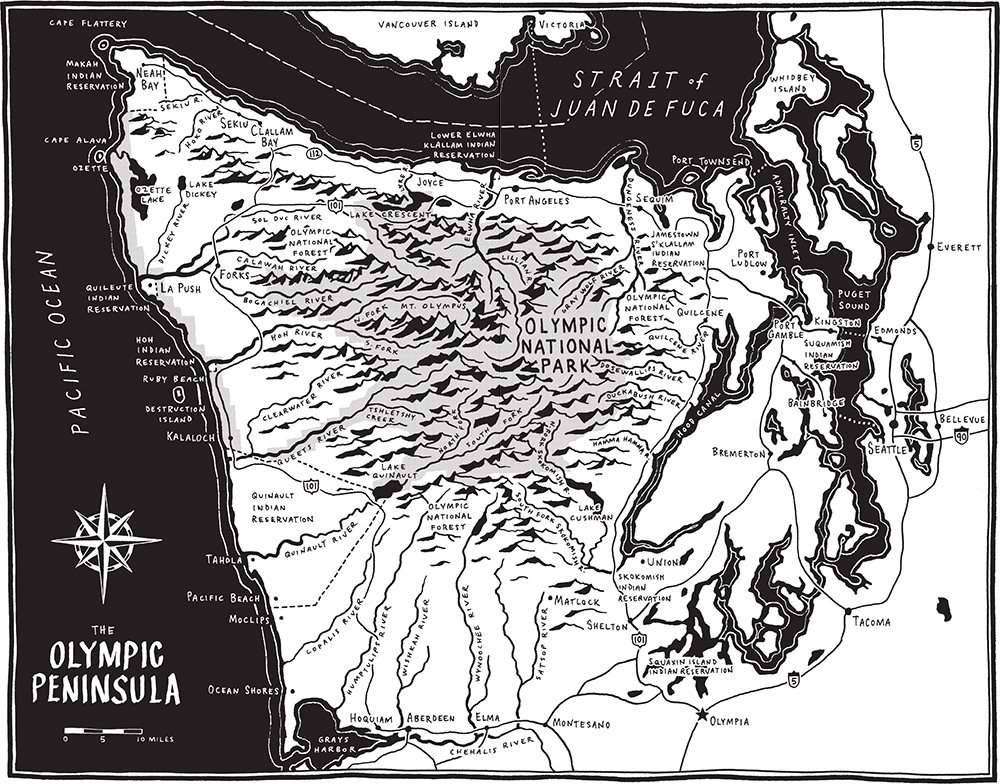

MAP: Thomas Eykemans

The paper used in this publication is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI z39.481984.

This book is for Otto and Phyllis Goldschmid

CONTENTS

Introduction

Tim McNulty

INTRODUCTION

During the cold, wet winter of 1972, my first on Washingtons Olympic Peninsula, the old Carnegie Library in Port Townsend was a sanctuary. It had the familiar classic lines and welcoming wooden furniture of my childhood library in New England. From the front steps above Lawrence Street, the snowy peaks of the Cascades arrayed in brilliant view across the inland sea. I was a young arrival in a new land, and the shelves of the Pacific Northwest section unlocked the regions stories for me. Among the well-worn tales of shipwrecks, logging feats, and Native American and pioneering histories was Murray Morgans already-classic The Last Wilderness. It fell into my hands like a cloth-bound Rosetta stone.

In the half century since, Ive explored, researched, and written about the rugged corners of this iconic landscape: mountains, rivers, forests, and seacoast. In younger years I drew my living from its traditional economy, planting trees, clearing trails, thinning, logging, and cutting firewood in the forests. Ive taught the natural history of the Olympic Peninsula and advocated for its preservation. Throughout, The Last Wilderness has remained a touchstone, a foundational text for this wild, quirky, and utterly magnificent landscape. Murray Morgans eye for telling detail, his ear for dialog, and his exquisite sense of storytelling animate his writing and distinguish The Last Wilderness from a shelf-full of books about the Olympic Peninsula, historical and recent. More than six decades since its publication it remains the definitive book about the peninsula, a region that has inspired more than its share of worthy titles. Nearly 3.5 million visitors to Olympic National Park each year confirm that the peninsula looms large in the American imagination. And Murray Morgans scrupulously researched and delightfully told stories of the peninsulas history still remain its best introduction. Hands down.

As a writer I had occasions to correspond with Murray. We spoke on the phone a few times, and he was always generous and encouraging. Its a disappointment that, in spite of my longtime friendship with his daughter, Lane, and earlier friendships with mutual friends of Murrays, we never met. Through his words and stories, Murray shared a love and enthusiasm for a place that has been the focus of so much of my own life. That may be one reason his book endures so well for me. In a way Murray has given us all the family story of the Olympic Peninsula. Through it, we can experience the peninsulas near-mythic past and delight inor be maddened byso much that takes place in the last wilderness today.

When Murray Morgan arrived in Hoquiam for his rookie reporters job at the Grays Harbor Washingtonian in the spring of 1937, he was in possession of a bachelors degree in journalism from the University of Washington and a curiosity as pitched and sprawling as the rough-edged landscape that took him in. Hoquiam and Aberdeen, a pair of rain-drenched mill towns at the head of Grays Harbor, anchor the southwest corner of the Olympic Peninsula. Rugged and remote, the peninsula is a fist of land thrust north between Puget Sound and the Pacific Ocean, as Morgan described it, a wilderness area of six thousand square miles. Morgan was captivated by this largely unchronicled corner of the Northwest. It was, he noted, the first land in the Pacific Northwest to be explored by explorers, the last to be mappedthe last wilderness.

Growing up in Tacoma, Morgan was no stranger to the island-like range of jumbled peaks and dense forests that loomed to the west. Some of his earliest memories were of trips with his family to the shore of Hood Canal near Lilliwaup. He remembered Indians, likely from the nearby Skokomish Reservation, fishing the calm waters and log handlers sluicing logs through a flume over the cliff and into the canal. That would have been about 1920, when the first round of coastal logging on the canal was coming to its end, and steam-driven logging railroads pushed up peninsula river valleys. History was catching up with the last wilderness, and Morgan would soon chronicle a time when the old resource-based Northwest was giving way to todays more recognizable landscape.