ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is dedicated to Oklahoma Cherokee basket makers: past, present and future. Although American Indian basketry was generally womens craft in earlier times, this study also recognizes three men whose interest in American Indian basket history led me to write this book. I was working at the American Indian Archaeological Institute (now the Institute for American Indian Studies) in Washington, Connecticut, when I first met Claude Medford Jr., Choctaw, of Natchitoches, Louisiana. In 1984, I invited him to participate in a Woodland basketry symposium and also invited Martha Ross, Cherokee basket maker of North Carolina, who remained a lifelong friend. Claude initially seemed to be a vagabond, traveling and staying extended times with various people. I soon realized he was a dedicated researcher, giving his all to baskets and arts of the Woodlands, and was doing so in the face of obstacles that would deter most people. We began corresponding, and his multi-page letters provided generous information. I made a finger-woven sash for him and gained one of his beautiful cane baskets in exchange. That basket now resides with the National Museum of the American Indian, and my sash is at the Williamson Museum in Natchitoches, where all the fine things Claude collected went when he died too early. I also gave my letters from Claude to the museum, as did many other people (hardly anyone threw away his typed single-spaced, multi-page letters). Occasionally I still come across one, in an obscure file or pressed in a pertinent book, and Claude speaks to me again. When I moved back to Oklahoma around 1990, Claude advised me to look up Marshal Gettys at the Oklahoma Historical Society. Marshal was also dedicated to southeastern baskets, but from another perspective; he was a collector and a historian. He gained the ability, like Claude, to discern materials, methods and differentiations denoting one tribes work from another. Marshal set me to this writing assignment, and he, too, left this world too soon. I was just learning about old baskets under his tutelage, and now, regrettably, I know just enough to be dangerous. The third man (number one in my life) is my husband, Jim Roaix, who enjoyed late-night sessions of basket making when Claude happened to visit us. Jim, of Maine, grew up using Micmac-produced ash baskets in potato field harvests, and he and Claude exchanged information and practiced each others crafts into the wee hours, powered by coffee, pastries and an occasional potato baked in the microwave. Jim, who, like me, also enjoyed Marshals vibrant personality and knowledge, continues to aid me with his own experience, a keen love of indigenous arts and his desire to assist me in my pursuit of capturing history.

The following individuals, roughly in order of contact, assisted this work by personally providing me with information and/or assistance affecting this published study: Mary Ellen Meredith, Tom Mooney, Mickel Yantz, Sharilyn Young, Christina Burke, Thomas Young, Patricia Nietfeld, Eric Singleton, Bob Pickering, Laura Bryant, Ollie Starr, Barbara Starr Scott, Bessie Russell, Anna Sixkiller, Jackie Coatney, Loretta Buffington, Billy Joe Sapp, Kathryn Roastingear, Linda Taylor, Clara Sue Kidwell, Mary Beth Nelson, John Timothy, Kimberley Gilliland, Terra Coons Fredrick, Matt Anderson, Dayna Lee, Luke Williams, Dana Talbert, Brenda Bradford, M. Anna Fariello, Catherine Sease, Roger Colten, Barbara Duncan, Jerry Catcher Thompson, Feather Smith, Stephanie Allen, Leta Jones, Matt Reed, Ketina Taylor, Shannon Fisher, Jacquelyn Reese, Ken Masters, Sarah H. Hill, Ted Foster, Ken Foster, Carolyn Chumwalooky, Jules-Marie Thornton, Mary Kay Henderson, Bobbie Gail Smith, Christy Sequichie, Rachel Henson, Nathan M. Gerth, Sheila Swearingen, Scott Swearingen, Steven Herrin, Rachel Mosman, Darcy Marlow, Phillip Viles, Vivian Cottrell, Mike Dart, Lisa Rutherford, Tennessee Loy and deepest thanks to Jeff Ross Davis, who served as a miracle worker with the photographs I amassed from a variety of sources. Apologies to all I overlooked.

INTRODUCTION

Basketry serves as an enduring thread of Cherokee culture in Oklahoma. Fifteen thousand peaceful and productive Cherokee people were forced to relocate to what is now Oklahoma 175 years ago. Cherokee basket makers faced tremendous challenges during and following their removal to the West. Today, six to eight generations later, most Cherokee citizens living in the Cherokee Nation know the names of their antecedents who traveled the trail or moved west earlier or came later. Cherokee basket makers can be proud of their own tenacity and achievements. Their craft, due to basket maker persistence, represents one of the pinnacles of Cherokee cultural survival.

The market for Oklahoma Cherokee baskets is currently robust, but it has not always been so. Despite the fact that Cherokee basketry never disappeared in Oklahoma, the craft was long ignored in national and regional studies of indigenous basketry. The first major book regarding indigenous baskets, Indian Basketry by George Wharton James, was published in 1901 with over 250 illustrations, yet the only mention of Cherokee basketry is a short reference about use of dyes. Next, Otis Tufton Masons two-volume 1904 American Indian Basketry, with 460 illustrations (none Cherokee) and more than five hundred pages, used only a paragraph to acknowledge the fineness of early Cherokee cane basketwork and ignored the continuation and evolution of the craft.

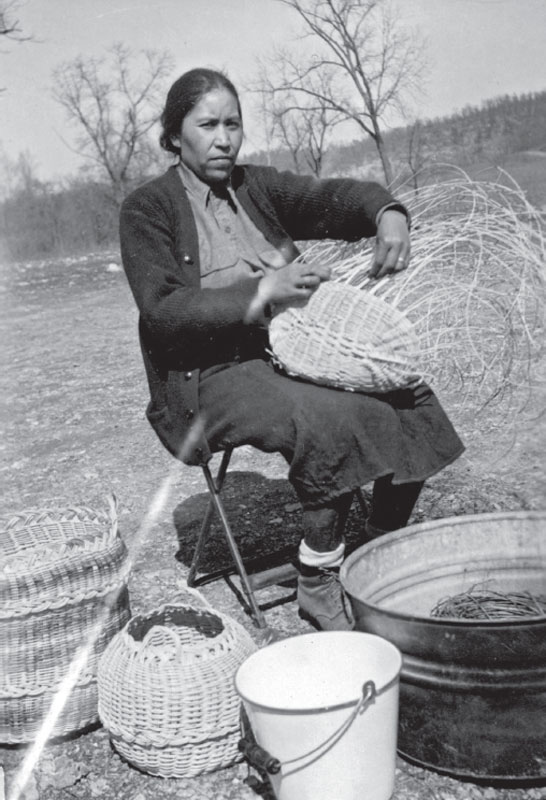

Eliza Proctor of Kenwood Community working on a buckbrush basket in 1941. National Archives at Fort Worth.

Lena Blackbird made this large buckbrush basket with knob-handled lid decorated with an ear of corn, now in a private collection. Jeff Davis.

While Cherokee culture was studied by ethnographer James Mooney beginning in 1885 until his death in 1921, Mooneys work did very little to further interest in the development and continuation of Cherokee material culture, including baskets.

Ethnologist Frank G. Specks 1920 Decorative Art and Basketry of the Cherokee, published as a