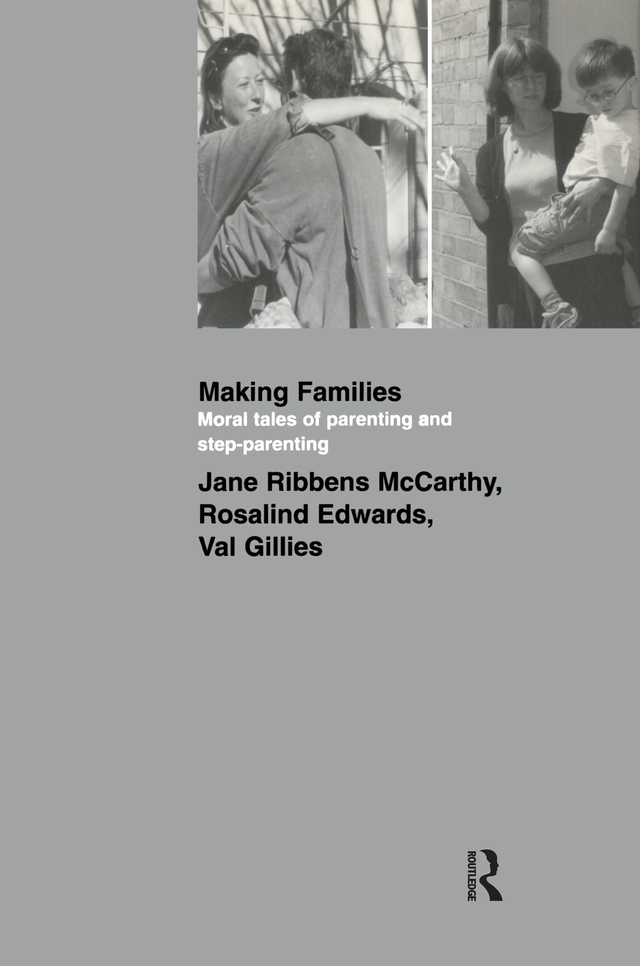

First published 2003 by Sociology Press

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Jane Ribbens McCarthy, Rosalind Edwards and Val Gillies 2003

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without the prior permission of the publisher.

This book may not be circulated in any other binding or cover and the same condition must be imposed on any acquiror.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 13: 978-1-903457-05-4 (pbk)

We would like to acknowledge the Economic and Social Research Council for funding the study on which this book is based, 'Parenting and step-parenting after divorce/separation: issues and negotiations', under grant number R000236288. There are also a number of colleagues whom we would like to thank for their support, advice, discussion and debate over the course of the empirical research and the writing of this book. In particular, we are grateful for the input of our advisory group: Linda Bell, Julia Brannen, Dorit Braun and David Morgan. Other people who have been important in developing our ideas include: Margareta Bck-Wiklund, Maren Bk, Graham Crow, Catherine Donovan, Simon Duncan, Brian Heaphy, Janet Holland, Ann-Magrit Jensen and Jeffrey Weeks. We would also like to acknowledge Sue Kirkpatrick's contribution, supporting us in further analytic work in the early stages of writing this book. Any deficiencies in our ideas or arguments, however, should be laid at our door. Finally, we are grateful to the parents, step-parents and children who took part in our research, for sharing their lives and feelings with us. We hope that we have presented these 'fairly', in all senses of the word.

Chapter 1

Constructing (step-)families: continuity or difference?

'It's a word,' Josie said to the still children. 'Family is a word. So is stepfamily. Step-family is a word in the dictionary too whether you like it or not. And it's not just a word, it's a fact and it's a fact that we all are now, whether you like that or not, either.'

(Joanna Trollope, Other People's Children, 1998: 84)

Families are widely discussed in Western societies as breaking down or as radically changing, with both policy-makers and people generally struggling to make sense of these shifts. How we chart a map of these changes, however, is highly contestable. Josie, the step-mother in Joanna TroI lope's novel quoted above, indicates one of the contours that may be drawn on these new (or maybe not so new) maps: that between 'ordinary' nuclear families and step-families.

So, is step-family a word that represents relationships and preoccupations that are inherently distinct from those of 'ordinary' family life, and that people have to deal with whether they like it or not? This book addresses these issues, beginning from the stance that looking at step-families can tell us something significant about family life and parenting generally. We regard step-families as a form of critical case study. On the one hand, they can be seen as representing the forefront of family and lifestyle change. From this point of view, their potential placement outside of the 'conventional' can reveal the typical itself through contrast, as well as providing knowledge about differences. On the other hand, diversity of family forms may not necessarily mean diversity of family lifestyles: people in step-families may be drawing on images and meanings of 'ordinary' family in how they create and understand their lives together, Either way, as Jacqueline Burgoyne (1987) observed, step-families throw light on broader assumptions and values concerning families. They highlight fundamental issues in family life and parenting that people may want to re/ create and/or dis/continue under changing circumstances, as well as those that they may feel their situation precludes.

Literature addressing step-families, however, can often focus around, or take for granted, differences from 'normal' family life, rather than exploring similarities or overlaps. In this introductory chapter we will look at how stepfamilies are constructed in various commentaries on contemporary family life, legal discourses and literature on step-families and parenting, raising key tensions around continuity and difference that run throughout this book.

Works of fiction may also treat step-families as a fundamentally different kind of environment in which to bring up children. Joanna Trollope's Other People's Children, an acclaimed novel about middle-class step-family life, paints a picture of inherent tensions and resentments. The members of the step-family at the centre of the book experience complex and tumultuous emotions as Josie and Matthew begin married life together, each with children from a previous marriage, in one household. Initially the adults involved do not want, cannot love, and cannot find a way to establish a relationship with 'other people's children'. Sometimes they are too self-absorbed in problems even to notice the suffering inflicted on their own children, who are made miserable and angry as their lives are disrupted by new schools, new homes and new parents. While Josie's ex-husband keeps his distance, Matthew's ex-wife is bitter and determined to undermine her children's relationship with their father and prevent one developing with their step-mother. Adults and children quickly reach breaking point, and step-family life becomes a fraught and bleak existence. At the height of crisis, however, people pull back from the brink. Allegiances and loyalties begin to form. Connections are being made, they are beginning to 'fit together' and find a common purpose:

'Maybe,' [Josie] said, 'we've got a sort of chance now. Maybe we could start, well, mending things after all that breaking. If - if we stopped being afraid of being a step-family, that is.' She folded her right hand over her wedding ring. 'I know I'm not your mother. I never will be. You've got a mother. But I could be your friend, I could be your supporter, your sponsor. Couldn't I? Sometimes hard things turn out better because you've had to make an effort to overcome them.' She stopped. 'Sorry,' she said. 'I don't want to lecture you.' She took her hands off the table and put them in her lap. 'I really just want to say that we may be a different kind of family, but we don't have to be worse. Do we?' (Troiiope, 1998: 277)

Trollope's story raises a number of pertinent questions. What does it mean to 'be a family'? Do people in step-families see themselves as making a different kind of family? Is individual happiness in a couple relationship prioritised at the expense of responsibilities towards children? Can a step-parent ever be regarded as the same as a biological mother or father? What do people in stepfamilies do to try to make step-family life work? It is these and similar issues that this book seeks to explore. It is concerned with how biological and stepparents themselves make sense of parenting, both within and between households, and within the wider social context. It looks at how people create, understand and experience their parenting and family lives. It reveals how these understandings are rooted in a strong moral sense of responsibility, but that what such responsibility constitutes varies according to gender and social class. In this focus, then, the book goes to the heart of academic, political and popular debates, and professional concerns, about the nature of contemporary family life and parenting.