I am truly grateful to the New York Public Librarys Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers for providing the space, time, and resources as I embarked on this project, with special thanks to Jean Strouse and Adriana Nova. My thanks to my editor, Jonathan Galassi, for his belief in this story, and for his encouragement, patience, and wisdom. Thank you to Gena Hamshaw, for her attentiveness, advice, and friendship throughout the process; to Wah-Ming Chang, for her special efforts on behalf of this book; and to my wonderful agent, Sarah Chalfant, for her help in shaping this idea and for finding a good home for it.

For those conversations, which directly and indirectly helped me through the process, thank you: Carol Munter, Jim Kincaid, Jennifer Egan, Farai Chideya, Maceo Senna, and my newfound aunts, Carla Latty and Crescentia Sugar Coutinho.

Thank you to Catholic Week and Catholic Charities for providing much needed materials.

I am ever grateful to Betty Jean Foy and Yvonne Jones, who welcomed me into their homes and were my guides on my trip to Alabama, offering me invaluable information about our family history. Thank you to Willie Maryland at the Alabama StateArchives, the late, great Odessa Redding, Dr. Norman C. Francis of Xavier University, and Xavier University of Louisiana archives.

Thank you to my husband who was at the other desk writing as I wrote this, and whose love and support sustained me as I struggled to tell this story.

To my father, who shared his life stories with me and included me in his own investigation into the truth of his origins, this story in so many ways belongs to you. Thank you for understandingas one writer to anotherthat we all have our own truth to tell.

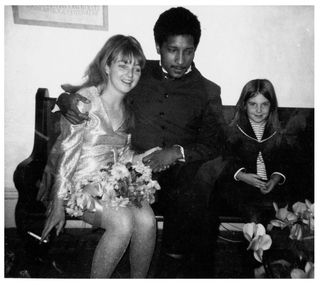

In 1975 my mother left my father for the last time. We fled to Guilford, Connecticut. It was a rich town, but we rented an apartment in a tenement that the towns residents referred to only as the welfare house. The backyard was a heap of dead cars. We lived on the second floor. Below us lived the towns other nonwhite residents, a Korean war bride and her two half-Italian sons. Beside them lived an obese white woman and her teenage son.

I dont know if we were officially hiding out from my father thereor if he knew where we were all that time. In my memory it seems that a long time passed before we saw him again, long enough for me to forget him. And I remember the day he reappeared. I was five, and I heard the doorbell ring. I raced in bare feet to see who was there. I saw, at the bottom of the dimly lit stairwell, a man. His face was hidden in the shadows, but I could make out black curls, light brown skin.

Hi, baby, he called up to me.

I stared back.

Dont you know who I am?

I shook my head.

You dont know who I am?

I knew and I didnt know. I had memories of the man at the bottom of the stairwell, both good and badbut I could not say who he was. I only knew that I had known him, back there in the city, and the sight of him now made me uneasy.

My mother emerged behind me in a housedress. I heard a sound in her throata gasp or a sighwhen she saw whom I was talking to.

See that? the man shouted up at her. See what youve done? She doesnt even know who I am. My own child doesnt recognize me.

I began to cry, perhaps recalling now all that we had fled. My mother shushed me. Its your father, she said, gathering me into her arms. I turned to watch him come toward us up the stairs.

Thirty years later, and hes still asking me that question. Dont you know who I am?

T here is always that momentfragile, briefwhen I see my father coming toward me from a distance, and I am happy. Particularly in odd places, far from home, like the time he came to visit me at the artists colony in New Hampshire. Id been there a few weeks already and had bonded with the other colonists in that fast and furious way friendships can form in isolation. At an artists colony you live in a bubble, separate from past and present and future. So it felt odd, a little bit intrusive, to have a person from my outside life come visit. But when my father called and asked if he could pop in one afternoonit was only a few hours drive from Rhode Island, where he livedI felt a wave of homesickness and agreed to see him.

I remember sitting and waiting for him in the common room in front of the big picture window surrounded by a crowd of other colonists. It was midday, prime work-time, but as I sat there waitingand my father was late, very late, as usualpeople trickled in one by one, until a small crowd had formed around me. I hear youre waiting for your father, more than one remarked as they settled onto the couch beside me. And itstruck me at some point that they were waiting to see my father too. It was curious to me that they would want to meet him. I wondered why they would not prefer to be working in their cabins, the way theyd come here to do.

As I watched the snow fall slowly outside the window, a thought crept into my mind. I wondered if they were gathered around me out of that old racial curiosity. I thought perhaps they wanted to see if it was true, if somebody who looked so like one of them could really have a black father. It was that old fault line again, and I felt alien from the colonists whom Id grown to feel were my friends over the past weeks. I felt what Id felt so many times in my life, that I was a specimen. And I wanted them all to go away so I could wait for my father in private.

And then I saw his blue pickup truck pull up in the driveway outside, and I said, rising, Thats him. Hes here. The group around me became quiet, and they all stared out the picture window as he stepped out of his pickup truck in a trench coat, a hat on his head, and made his way across the gravel to the white farmhouse where we waited. I saw him through their eyes, and I felt a surge of pride as I watched him walking through the snow. Pride that he was my father.

My father is handsomeon his good days, even now, when he has not been drinking or eating too much, he is strikingly handsome. A hush fell over the group as they watched him approach. He came through the door, and I felt the eyes of the others on us as I rose to greet him. I hugged him hello, and I remember I made a show of being more affectionate toward him than I would have been if we were unobserved. I felt the need to perform our closeness. In that embrace I wanted to show that I was with him, not them. No matter how friendly Id been toward them the past few weeks, they did not know the real me.

After the embrace I turned around and introduced him to them, and for a moment everything was perfect. He had not revealed himself. He was just a mysterious, handsome black man in snappy clothes, a mystery manthe paper-doll hero out of a Sidney Poitier moviewho had shown up in New Hampshire to visit his writer daughter. And if I could freeze it there, in that moment of him nodding his head hello, he would be the perfect fatherthe father of my childhood daydreams. That was what he was to the crowd of white faces who stared at us. I imagined I had gone from being just one of the other colonists to being something far more interesting because of this man by my side.

After theyd all said hello, I shuttled him out the door, saying I wanted to show him my studio. I needed us to disappear quickly before he could do anything to ruin the picture.