Thank you for downloading this Touchstone eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Touchstone and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

We hope you enjoyed reading this Touchstone eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Touchstone and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Touchstone

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2013 by Stephanie Davis

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Touchstone Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Touchstone hardcover edition April 2013

TOUCHSTONE and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Ruth Lee-Mui

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Davis, Steph.

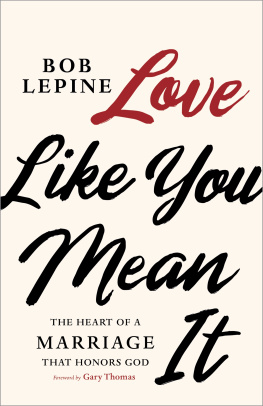

Learning to fly / Steph Davis.

p. cm.

1. Davis, Steph. 2. Women mountaineersUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

GV199.92.D38A3 2013

796.522092dc23

[B] 2012029998

ISBN 978-1-4516-5205-5

ISBN 978-1-4516-5207-9 (ebook)

for Fletch

I want to push myself to my limits, and if things dont work out, then I can give up. But I will do everything I can until the bitter end. That is how I live.

HARUKI MURAKAMI

So Ive started out for God knows where

I guess Ill know when I get there.

TOM PETTY

Contents

The Roan Plateau of Colorado

F alling into dead air felt nothing like I thought it would. Id spent much of my life trying not to think about it. It was my worst nightmare. After twenty years of going up rock faces and mountains, the idea of free-falling through the air was essentially x-ed out in my brain. Because you cant think about falling when youre climbing, or you wont go climbing anymore. In the few instances during my climbing career when my mind had flicked there, Id yanked it right back. I figured if the big fall ever came, it would all be over, wham , just like that. Id slip off. Id start falling. A stab of panic. Then somehow I would just disappear or everything would go black or something. And that would be it. The end.

As it turns out, nothing could be further from the truth. You know youre falling for every millisecond of time your body is dropping through the air. You see the wall rushing past, the colors of the rock streak by, the ground coming at you. You see trees getting bigger, small rocks grow into giant boulders. Your brain knows exactly whats happening and where youre going: directly to the ground, faster and faster as you fall until you reach terminal speed, 120 miles per hour. And each of those milliseconds feels as long and full as some years.

Between my feet, a small runnel trickled toward the edge and scattered into clear, round droplets that cascaded into the air. The edge was square, like the front of a counter. I looked at my boots, coming right up to the end of the flat limestone, and then down past them. The wall dropped six hundred feet to meet a gray talus slope. The small rocks poured down to steep, rugged gullies and ravines, a thousand more feet rendered tiny by distance. The shift between the big view and the closeup view was disorienting, like refocusing a camera lens. I felt almost mesmerized and slightly vertiginous, watching the sparkling water balls drop out in space. I jumped.

Chapter 1

Falling

The Perrine Bridge, Twin Falls, Idaho

Ive been a rock climber for twenty years. So for two decades, Ive been motivated by fear or pride, or both, not to fall. I would have picked myself as the second-least-likely person I know to ever go skydiving. The first being my mom.

First of all, Im not a thrill seeker. Second, like any serious climber, Im inherently cheap, and skydiving is expensive. Third, I dont prefer being scared. Falling, loud wind, cold air, hitting the ground hard... these are all things I also dont usually go out looking for. In the few years before the summer of 2007, I had become friends with several skydivers and base jumpers, and we all knew it would be a cold day in hell before Id be sitting in a jump plane or standing at the edge of a cliff with them.

Its funny, though, how many times the thing you are least likely to do is what you find yourself doing. Or at least thats how it is for me. I grew up a studious, aspiring concert pianist with a masters degree in literature, then subsequently dropped out of law school to live in a truck and become a professional climber, so Ive learned not to rule anything out.

Salt flats of the Great Salt Lake, Utah John Evans

My husband and I met in our early twenties, when we were both living out of cars and climbing as much as possible, waiting tables sporadically to sustain the traditional spartan, road-tripping existence of the climbing bum. Over the next twelve years, we traveled together, split up, reunited, climbed huge walls and mountains with ropes and without ropes, lived in vehicles, tents, and snow caves, and finally got married. We grew up together wildly and freely, challenging each other all along the way. Our life was pure adventure and self-invention, and nothing about it was safe.

I grew up in various suburbias in Illinois, Maryland, and New Jersey with one older brother and a cat, and my parents could never get their heads around my transformation from a model student into an itinerant climber. Though my ascents had quickly blossomed from basic outings into major ascents of big walls and peaks in Yosemite, Baffin Island, Pakistan, Patagonia, and Kyrgyzstan, they couldnt get comfortable with my non-usual lifestyle and nontraditional choices, even as climbing began to develop into a career. At the end of the day, I was still usually eating out of a camping pot, pulling a paycheck that must have seemed like a joke to someone whod had every reason to bank on a lawyer daughter to match the doctor son.

To a climber, it looked like the dream lifemarried to my longtime partner, climbing big routes around the world, sponsored by a major outdoor-clothing company and a few other equipment manufacturers. And then, in 2006, my husband climbed a famous sandstone arch in a Utah National Park and a media uproar erupted in the outdoor world. It was just a hunk of sandy, crumbly sandstone, less than a hundred feet tall, surrounded by hundreds of miles of other, better rocks to climb, hardly a five-star route. But its shape made it a tourist attraction, and the Park Service had even glued and cemented it to hold it together and chiseled out steps in the slabs leading up to it. The Park Service was first annoyed by the climb and the media focus, then out for blood, and the media whipped up as much controversy as could be invented out of the situation.

Next page