CONTENTS

1485 Victory at Bosworth for Henry Tudor sees him crowned King Henry VII of England.

1509 Henry VIII becomes King of England.

1533 Henry VIII divorces Queen Catherine of Aragon to marry Anne Boleyn.

1540 Henry VIII divorces Anne of Cleves and marries Catherine Howard.

1547 Henry VIII is succeeded by his son, Edward VI.

1558 Elizabeth I becomes Queen of England.

1560s Religious wars take place in Europe between Protestants and Catholics.

1580 Francis Drake and his crew return to England after sailing around the world.

1587 Mary Queen of Scots is executed.

1603 Elizabeth I dies and James VI of Scotland becomes James I of England.

1503 James IV of Scotland marries Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII.

1517 German priest Martin Luther sparks the Protestant Reformation.

1534 The Act of Supremacy makes Henry VIII head of the English Church.

1542 James V dies and his infant daughter becomes Mary Queen of Scots.

1553 Mary I becomes Englands queen.

1561 Mary Queen of Scots returns to Scotland from France.

1567 The future James VI of Scotland is born; his father Lord Darnley is murdered.

1586 The Babington Plot to murder Elizabeth I is uncovered.

1588 The English fleet defeat the Spanish Armada; Englands war with Spain lasts until 1603.

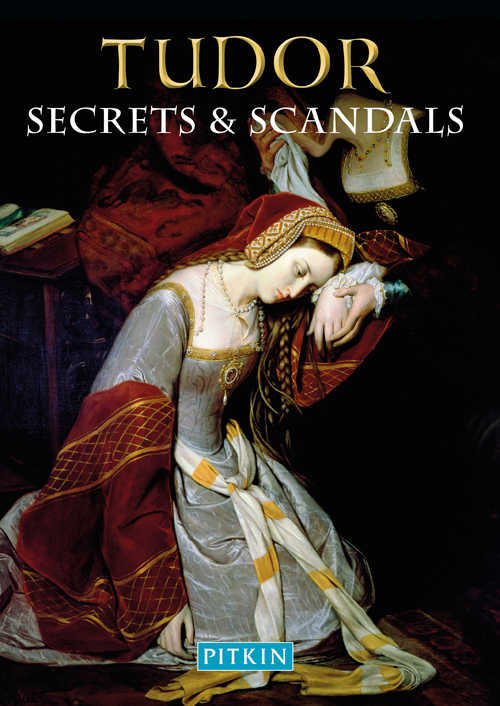

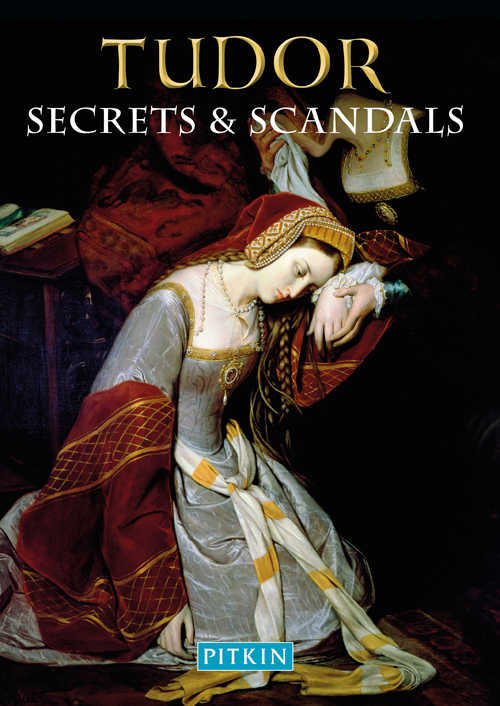

T he Tudors ruled England from 1485 until 1603, theirs an age of many secrets and frequent scandals. The rack and the gallows, the assassins knife, potions and poisons, backstairs intrigue, scheming lords and maligned mistresses, alchemy and magic, science and superstition, religious wars and buccaneering exploration on the high seas Tudor life was a heady brew, a vibrant time of adventure, change and danger, from the glittering court to the seamy underworld. The crowns of Tudor England and Stuart Scotland rested uneasily, and few close to the throne slept without cares. Todays heroes were often tomorrows villains, for scandal, treason, misplaced trust or a secret laid bare could tumble the highest to the block or the hangmans rope.

T he Tudor dynasty seized the throne of England in 1485, when Henry, son of Edmund Tudor, became King Henry VII and ended the long Wars of the Roses. Yet in peace the new regime was insecure and the air thick with rumour and intrigue. Neither ally nor enemy could be trusted and there were many dark secrets the darkest surrounding the vanished Princes in the Tower, the young sons of Edward IV. The new kings crown rested uneasily, for dark secrets were hidden in the candlelit corridors of power.

SECRETS OF THE CAR PARK

The Tudor victor paid scant respect to his defeated rival: after Richard III lost his crown and his life in the Battle of Bosworth, his corpse was stripped and mutilated and buried in the priory of Grey Friars in Leicester. But the priory was destroyed in 1538 and it was long believed that the royal bones ended up in the river. However, in 2012 a grave was found by archaeologists, beneath a Leicester car park, and DNA evidence (from the lineage of Richards sister) confirmed the remains as those of Richard III. Forensic evidence indicated he had one shoulder higher than the other, hence his nickname crookback, and also how he died, one of several battlefield blows slicing off part of his skull. Richard was given a royal reburial, but his reputation remains contentious.

The bones of Richard III, discovered in a car park in Leicester University of Leicester.

Henry VII, the first of the Tudor monarchs of England (painting c .1626).

HENRY AND THE PRETENDERS

Having seized the crown in battle, Henry feared Yorkist counter-revolution. Edward IVs sons (the Princes in the Tower) had disappeared and Richard IIIs only son had died aged 10 in 1484. The late kings nephew Warwick (son of the executed Duke of Clarence) was locked away. When a bakers son of the same age called Lambert Simnel appeared pretending to be Warwick escaped to Ireland, Henry displayed the real Warwick briefly in London to scotch the rumours. Simnel was crowned Edward VI in Dublin and with a small army crossed to England, to be defeated in June 1487 near Newark. Henry scornfully sent the failed pretender to work, first in the kitchens, then as a falconer.

Ten years later another Warwick appeared; Ralph Wilford was executed in February 1499, along with the friar who had taught him to impersonate Warwick. A more serious threat was posed by the Fleming Perkin Warbeck, claiming to be one of the Princes in the Tower and calling himself Richard IV. After Warbecks armed uprising in 1495 fizzled out, he was treated surprisingly gently, kept under house arrest at court until 1498, when he tried to escape. He was put in the stocks and forced to confess. A second escape plan in 1499, involving the hapless Warwick, was a gamble too far, and in November that year Perkin Warbeck was hanged at Tyburn. Warwicks short, unhappy life as a royal prisoner ended weeks later, also on the scaffold.

ROYAL LADIES

Young, highborn women were sent to court to advance their social standing and attract wealthy husbands. A maid of honour was young and single; a lady in waiting usually married and sometimes rich in her own right (such as Bess of Hardwick). Court ladies provided companionship and back office help for the queen and diversion for the king and his courtiers. Some secretly, or openly, became royal mistresses.

The murder of the two Princes in the Tower.

HENRY AND CATHERINE

The open secret of royal success was to remove rivals and sire sons, preferably with a spouse who brought diplomatic gains to the marriage bed. Henry VIIs eldest son Prince Arthur married Spains Princess Catherine of Aragon in 1501 a useful match but Arthur died a year later. Spain demanded the repayment of Catherines dowry, but Henry, ever parsimonious, kept the money: he considered marrying the princess himself, since his wife Elizabeth of York died in 1503, but instead he betrothed her to his younger son Henry, then 11.

Arthur, Prince of Wales, son of Henry VII. Drawing from the north window of Jesus Chapel, Priory Church, Great Malvern.

Henry VIII became king in 1509 and married Catherine. There seemed to be no scandals or secrets: the young king was handsome, talented, full of promise. Civil war memories were fading, the murky past rewritten in a politically correct pro-Tudor light. While Henry dreamed of military glory, his pressing need was a son. Great was his joy when Catherine became pregnant, but the infant (a boy born on New Years Day 1511) died within two months. Four more pregnancies produced only one healthy child, a daughter, the future Queen Mary I.

Next page