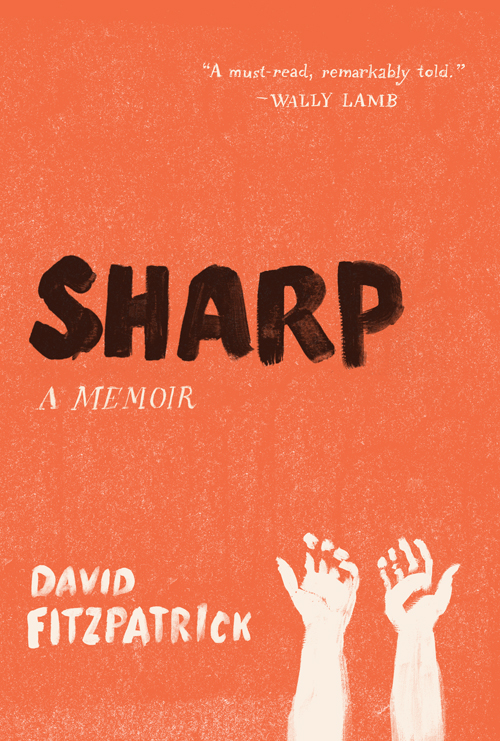

Fitzpatrick - Sharp: a Memoir

Here you can read online Fitzpatrick - Sharp: a Memoir full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York;US;United States, year: 2012, publisher: HarperCollins US;Harpercollins Publishing Aust, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Sharp: a Memoir

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins US;Harpercollins Publishing Aust

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- City:New York;US;United States

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sharp: a Memoir: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Sharp: a Memoir" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Sharp: a Memoir — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Sharp: a Memoir" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Sharp

A Memoir

David Fitzpatrick

For Amy and my Mom and Dad

This is a work of nonfiction. The events and experiences I have detailed herein are all true and have been faithfully rendered as I remember them. In some places, Ive changed the names, identities, and other specifics of individuals who have played a role in my life in order to protect their privacy and integrity, and especially to protect other patients I encountered over the years, who have a right to tell their own stories if they so choose.

The conversations I re-create come from my clear recollections of them, though they are not written to represent word-for-word documentations. Instead, Ive retold them in a way that evokes the real feeling and meaning of what was said, in keeping with the true essence, mood, and spirit of the exchanges.

Contents

W hen I try to find an exact point when life was steady, blessed, and good, I always land in the summer when I was twenty years old, on Marthas Vineyard. This was three years before mental illness began to eviscerate me and left me for dead. It was before I started to slash my own body with razor blades in a fury that at times seemed otherworldly. It was before my college roommates became monsters and before recreational drugs played such a prominent role in my life. In the simplest sense, it was a golden time with high school buddies and a semiperfect girl who strolled into my viewfinder with ease and a lightness that disarmed me and made me laugh out loud.

Really, a time to soar.

That summer makes me ache with its mixture of portent and joy. What on earth would I tell my twenty-year-old self today? I know Id want to explain the horrid facts; Id want to protect him and warn him of the tsunami bearing down on his skull, but Id also start with the basics. Id begin with the positive and tell him to squeeze his shining lady tight, to taste her until his jaw ached, to go hard, strong, and brave and suck the dew out of the remaining dawns. Id tell him to play, write, whistle, dance, and screw with abandon; to inhale the tanning oils on every luscious shoulder; to guzzle a few Rolling Rocks at dusk with friends on the Circuit Avenue porch; to gorge on watermelon and swallow the seeds; and to feel the ocean stinging his eyes and dive right back under. To bodysurf on South Beach until his fingers and toes are pruned and blue, until his chest aches. And then to count the different varieties of butterscotch reflecting off the Gay Head cliffs at sunset. Oh, to know it would soon crumble and slip through his handswhat would that do to his capacity for joy? How precious do the clear head, tight belly, and pumping thighs become during the three-mile morning jogs? Oh, how succulent is the rain pounding the steaming blacktop!

Id tell the younger me to hang on and not give up. Id tell him so much more, of course. Id sit him down and ease his mind. Id give him details, to keep him from falling into the well, into the snake pit, but there are things I dont think hed be able to take in. Who is ready to hear that he wont be capable of articulating malaiseor that hell carve himself up brutally and after half a decade spent bleeding, the illness, the hospitalizations, and the inertia will become addictive and almost rote? Nor could he comprehend that his overly sedated, bloated, and numbed body would morph into that of a professional mental patient, just another circuit rider jumping from one institution to the next?

When the obliterating wave finally released me in 2006, what remained was a forty-one-year-old man who was fragmented, extremely timid, and certain of only a few things, one of which was how to describe my experience of illness. Ive read that Winston Churchill called it a black dog, others an enveloping fog or an avalanche of anguish, but Id be a lot more vague and general about it and say it was an inhuman darker force that felt worse than death.

Id call it the terror.

M y mother once told me about the first time her own mother was carried away by aides in white uniforms. I was six when they grabbed Nannie at the top of the stairs in Somerville, she said. As she left in the ambulance, she was screaming, My throat is burning, its on fire, my throat is on fire!

Ill never forget it, my mother said. She also told me about her older sister and how she, too, was institutionalized and had a couple of breakdowns while she was growing up. My mother, a young teen then, took a trolley car from Somerville to the Brighton mental ward to visit her sister. The hospital was set way back behind huge bushes and inside, up long, winding stairs. She found her sister on the eighth floor studying the traffic and trees from her barred window.

She was dressed up in a black hat and gray veil and was wearing these delicate white gloves, as if shed be going shopping at any moment. My mother stopped in her telling then and took a breath. She was ranting, lost, she said. The only thing I could do was sit with her, hold her hand. And so thats what I didthats what I had to offer.

My mother is the only one of her siblings not to have been hospitalized.

My family tree is spiked with mental illness. Its loaded with souls whove done their institutional timeaunts, uncles, grandmother, etc. Our clan is an unusually close group of facesloving, supportive, truly good people. And weve taken our psychic bruises. Emotional struggle wasnt discussed muchI know thats not unusual for Irish Catholicsbut we kept things especially hushed. Once in a while we picked up whispered facts involving several nervous breakdowns and institutionalizations. A grandmothers history of electric shock and numerous hospitalizations, one uncle running away from the pack and never wanting contact again, another who was bipolar and was treated with electric shock, and a great-great-grandfather who lived up on a hill away from his kids and wife in Ireland. His loyal wife brought meals to him each day.

My dad lost his sister to postpartum suicide when I was in sixth grade. (The child was born safely and was healthy, but my aunt died of an overdose of medication.) I remember sleeping over at her boyfriends apartment on the Lexington Green. This was in 1976, a few years before she married. Our whole clan had gathered to celebrate the Bicentennial. I ended up wetting the boyfriends pull-out couch, and I was so ashamed. But my aunt came over to me with a big grin that morning, her cheeks flushed and dimples blazing. She said, Dont you worry, mister, I wont breathe a word of it to any newspaper. In a few years, she said, kissing me on the nose, the girls in Guilford will be lining up to take you anywaythey wont care if you breathe fire, theyll just want to gobble up your smile.

She looked so beautiful that morning, that whole day, really. I couldnt ever imagine her with tears; it just didnt fit into my young brain. I assumed my aunt would zoom her way through life with rosy cheeks and marvelous dimples.

Depression also hit my father, a rock of rocks throughout my life. He struggled with it in his thirties, though he never spoke of it until later. The only example of sadness I remember from my dad is the morning after my brother Ted died, one day after he was born. I was seven, and my father rushed into our kitchen with tears and a fatigued, unshaven face. I pray youll never learn what its like to lose a child, he wept, slamming cabinets. That glimpse of anguish was the first time Id seen my father as vulnerable, and it shocked and frightened me. I obsessed about my fathers expression and his words and worried that one day I, too, would fragment in the same way.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Sharp: a Memoir»

Look at similar books to Sharp: a Memoir. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Sharp: a Memoir and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.