NAPOLEON IN EGYPT

CONTENTS

To Matthias

MAPS

Routes taken by Napoleons fleet and Nelsons squadron

Alexandria

Lower Egypt

Battle of the Pyramids Cairo

Battle of the Nile

Upper Egypt

Syrian Campaign

Siege of Acre

Battle of Mount Tabor

Battle of Aboukir

AUTHORS NOTE

Napoleon was of course merely General Bonaparte at the time of his invasion of Egypt. However, he remains for the most part better remembered in history as Napoleon. In accord with this popular conception, I have referred to him as Napoleon throughout (as indeed he did himself in his third-person memoirs of this period).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Once again, I am particularly glad to acknowledge the meticulous and perceptive editing of Jrg Hensgen of Jonathan Cape. I am also indebted to Will Sulkin of Jonathan Cape, who believed in the idea of Napoleon in Egypt and encouraged it. However, none of this could have come about but for my indefatigable agent, Julian Alexander of LAW, who as ever played such a leading role in the conception of this book.

Europe is a molehill.... Everything here is worn out.... tiny Europe has not enough to offer. We must set off for the Orient; that is where all the greatest glory is to be achieved.

Napoleon

The time I spent in Egypt was the most delightful of my life because it was the most ideal.

Napoleon

I saw the way to achieve all my dreams.... I would found a religion, I saw myself marching on the way to Asia, mounted on an elephant, a turban on my head, and in my hand a new Koran that I would have composed to suit my needs. In my enterprises I would have combined the experiences of the two worlds, exploiting the realm of all history for my own profit.

Napoleon

PROLOGUE:

THE SONG OF DEPARTURE

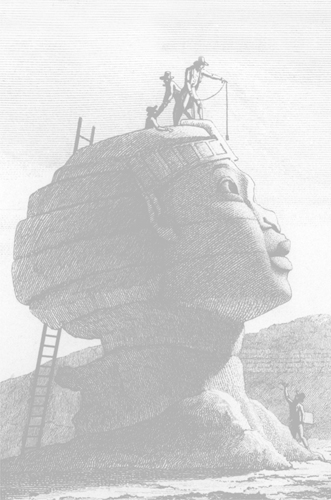

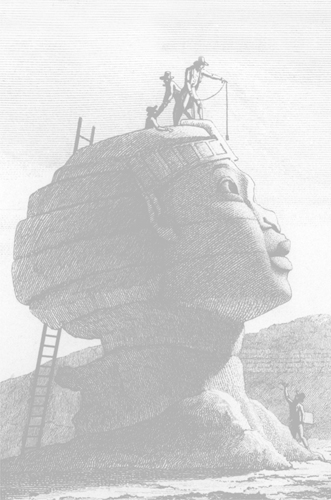

The invasion of Egypt by Napoleon in the summer of 1798 was the first great seaborne invasion of the modern era. At the time, it may well have been the largest ever launched in the Western worldat least on a par with Xerxes vast Persian fleet which attacked Athens at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC, and certainly double the size of the sixteenth-century Spanish Armada which attempted to invade Elizabethan England. Yet unlike these predecessors, Napoleons invasion involved a long sea voyage of almost 2,000 miles. His armada consisted of 335 ships, ranging from towering battleships and fast frigates to lowly transports, from those bearing a cargo of just forty tons to those carrying over 400 tons. Each of these ships carried full crews, and in all the fleet was loaded with 1,200 horses, 171 field guns and an official roll-call of 35,000 soldiers. In fact, the number of soldiers was almost certainly nearer 40,000: Napoleon exploited the opportunity provided by four separate main embarkation portsToulon and Marseilles in France, Genoa and Civitavecchia in Italyto surreptitiously increase the quota allowed him by the five-man Directory which ruled revolutionary France at the time.

Yet these were not the only unofficial additions to the expedition: as many as 300 women are also thought to have traveled aboard the fleet. A good number of these would have been the washerwomen and seamstresses who normally accompanied the French army at this time, but there were certainly many others smuggled aboard, contrary to Napoleons orders. These were mainly the wives of junior and middle-ranking army officers, who were hustled up the gangways dressed in officers uniform, their figures disguised by cloaks, their tresses swept up under military caps. As we shall see, these women would prove more than mere supernumeraries, and two in particular would achieve fame: one as Egypts new Cleopatra, the other spiritedly opposing a Napoleonic insult to women.

It took little time for Napoleon to become aware that these extra women had been smuggled aboard: he always made it his business to be well supplied with intelligence by spies, as much amongst his own ranks as amongst the enemy. Far from disconcerting him, this discovery meant he felt less compunction about initiating his own covert plan for female company. As arranged, after four days at sea he dispatched the frigate Pomone to collect his wife Josephine from Naplesa mission which proved fruitless because Josephine had capriciously decided not to travel to southern Italy.

After the convoys from the separate ports had combined at sea and begun sailing for the eastern Mediterranean, the invasion armada swelled to cover almost five square miles, often reduced to traveling at the stately speed of one knot. Each afternoon all soldiers were paraded for inspection on the wide decks of the ships of the line. Military bands, their brass instruments glinting in the June sunlight, played stirring marches, while Napoleon watched from the bridge of the aptly named flagship LOrient.

Napoleon cut a surprisingly unimpressive figure at this early stage in his career. He was thin as a rake and only five foot three inches tall. His gaunt, hard-eyed features, sullen in repose, were framed by long sideburns and lank shoulder-length hair. He was just twenty-eight years old. Yet this was very much a young mans expedition, and some of his generals were even younger. Promotion came fast to men of ability in the revolutionary army, and their sallow-skinned young Corsican leader was an inspiration to both his officers and his men. He had already conducted a brilliant campaign in Italy, putting the powerful Austrians to flight and defeating the pope. The men of the Army of Italy were all too willing to follow their leader on this expedition into the unknown. To improve morale, Napoleon encouraged the soldiers parading on deck to sing patriotic songs, and each afternoon their voices would ring out across the sunlit Mediterranean, taken up by other soldiers from ship to ship through the fleet. Their favorites were La Marseillaise and the stirring Chant du Dpart (Song of Departure):

Inspiring victory leads us through all barriers,

Liberty guides the footsteps of us warriors,

And from the north to the Midi we all

Hear the war-like trumpets call.

Tremble you enemies of France,

Our blood stirred with pride we advance.

The sovereign people are victorious,

All true patriots call on us:

A Frenchman must never ask why

For his country he must live or die!

Napoleon himself was a bad sailor, and in order to overcome seasickness he had ordered a special bed with casters attached to its legs to be installed in his cabin. This was intended to compensate for the rolling of the sea, and astonishingly it appears to have worked. Napoleon spent much of the voyage in bed, drawing up his plans for the invasion; this was his opportunity to emulate his hero, Alexander the Great. As he had confided to his secretary Bourrienne, prior to departure: Europe is a molehill.... Everything here is worn out. My glory is slipping from my grasp, tiny Europe has not enough to offer. We must set off for the Orient; that is where all the greatest glory is to be achieved. Napoleons choice of words here was particularly revealing: he spoke of the Orient, not just Egypt. Although the Directory was under the impression that he intended to invade Egypt, Napoleon harbored dreams of following in the footsteps of Alexander the Great, and marching all the way to India. When he had revealed to the Directory this extension to his plans, they had reluctantly assented to it, for the most part because they did not believe in it: this was merely the fantasy of a man intoxicated by ambition, and would prove impossible on the ground. In fact, as we shall see, Napoleon had already made detailed plans for the realization of this Oriental fantasy.

Next page