ALSO BY STEVEN WATTS

Mr. Playboy: Hugh Hefner and the American Dream

The Peoples Tycoon:

Henry Ford and the American Century

The Magic Kingdom:

Walt Disney and the American Way of Life

The Romance of Real Life:

Charles Brockden Brown and the Origins of American Culture

The Republic Reborn:

War and the Making of Liberal America, 17901820

Copyright 2013 Steven Watts

All of the photos are courtesy of Dale Carnegie & Associates, Inc., except for those of Carnegie and Frieda Offenbach, and Carnegie and Linda Offenbach, which are courtesy of Linda Polsby.

Production Editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Watts, Steven, 1952

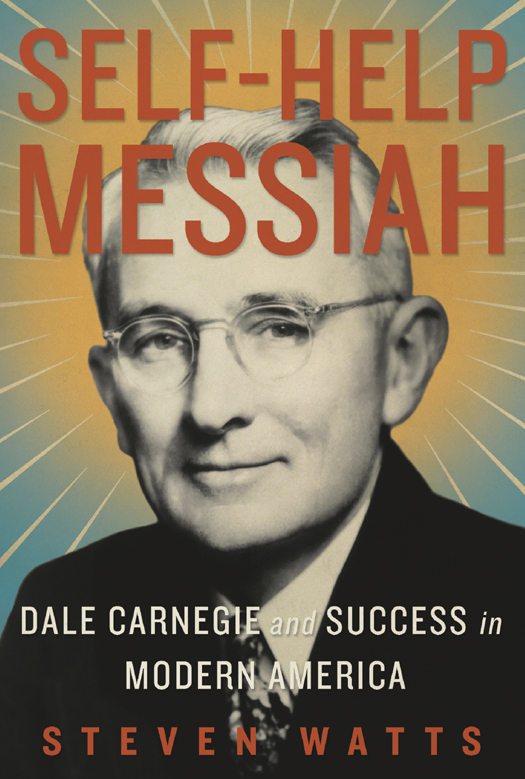

Self-help Messiah : Dale Carnegie and success in modern America / by Steven Watts.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-1-59051-503-7

1. Carnegie, Dale, 1888-1955. 2. Success. 3. Conduct of life. 4. TeachersUnited StatesBiography. 5. OratorsUnited StatesBiography.

6. Authors, American20th centuryBiography. I. Title.

CT275.C3114W37 2013

973.91092dc23

[B]

2013003227

v3.1

For all of my teachers, friends, and colleagues at the University of Missouri

Contents

Introduction

Helping Yourself in Modern America

O n a cold January evening in 1936, a great horde descended on the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York City. Three thousand people crammed into the grand ballroom and onto the balcony encircling it, while hundreds more stood shivering on the sidewalk outside, unable to find even standing room as the hotel staff frantically wedged the doors shut and hoped the fire marshal would not appear. The throng was responding to a series of full-page ads in the New York Sun that promised Increase Your Income, Learn to Speak Effectively, Prepare for Leadership.

Yet the crowd did not spring from the ranks of the working class or the desperately unemployed who were struggling to survive in the dark days of the Great Depression. It came from a more prosperous stratum, but one equally anxious about sliding into failureentrepreneurs, businessmen, shopkeepers, salesmen, middle managers, white-collar executives, professional men. As the audience listened attentively for the next hour, fifteen figures paraded before the single microphone on the stage and gave three-minute testimonials. Understanding the principles of human relations, the speakers proclaimed, had pointed them toward success. A druggist, a chain-store manager, an insurance man, a truck salesman, a dentist, an architect, a lawyer, a banker, and several others explained that learning how to deal with people had dramatically enhanced their careers and changed their lives.

After these endorsements, a short, trim man with steel-rimmed glasses, ramrod posture, and a sincere, soothing voice with a slight Midwestern twang took the stage. Dale Carnegie, creator of the self-improvement course being praised, admitted that he was gratified by the large audience. But, he added quickly, I have no doubt as to why you are here. You are not here because you are interested in me. You are here because you are interested in yourself and the solution to your problems. He assured the crowd that each listener could learn the techniques that had improved so many lives. Each could understand how to be a good listener, make people like them instantly, develop an enthusiastic attitude, handle difficult personal situations, and win others to their way of thinking. Each could be successful. Every student taking his course, he declared in conclusion, begins to get self-confidence. After all, why shouldnt theyand why shouldnt you? The throng leapt to its feet in thunderous applause and most of them rushed to tables at the back of the room to sign up for the class. In subsequent years, more than eight million students would graduate from the Dale Carnegie Course in Effective Speaking and Human Relations.

One year later, an even bigger event sent Carnegie rocketing to national fame. In January 1937, his book How to Win Friends and Influence People, which codified the lessons of the Carnegie Course, shot to the top of the best-seller list. It would go through seventeen editions its first year, and Leon Shimkin, Carnegies editor, sent him a somewhat dazed letter in March 1937, after the book had already sold a quarter of a million copies in only three months. If one year ago a friend of mine were to have told me that

At the heart of How to Win Friends lay a message that massive numbers of readers found irresistible: One could find success in the modern world by developing attractive personal traits, bolstering self-confidence, improving skills in human relations, getting people to like you, and adopting a psychological perspective in assessing and meeting human needs. Carnegie insisted that getting ahead in lifesecuring a better job, making more money, enjoying the esteem of your peerswas simply a matter of retooling your personality. With contagious enthusiasm, he promised that his advice book would help any individual to get out of a mental rut, think new thoughts, acquire new visions, new ambitions Win people to your way of thinking. Increase your influence, your prestige, your ability to get things done. Win new clients, new customers Handle complaints, avoid arguments, keep your human contacts smooth and pleasant Make the principles of psychology easy for you to apply in your daily contacts.

In such a fashion, Carnegie became one of the most popular and influential figures in modern American history. His message promoting sparkling personality, self-esteem, human relations, and psychological well-being resonated widely and deeply in society, attracting millions of acolytes and elevating him to a pinnacle of influence in shaping modern values. And his legacy was a lasting one.

So what explains Carnegies meteoric rise? Why did millions of ordinary citizens flock to his message of personality development, human relations, and success? Why was he able to become a major cultural figure in modern America? Answers to these questions lay partly embedded in a massive reorientation of American life in the early decades of the twentieth century, the remarkable era during which Carnegie labored and wrote. The United States found itself in the throes of rapid change as it transformed from a rural village republic to an urban society of jarring ethnic diversity, imposing bureaucratic structures, and bewildering social problems. From the 1880s to the 1920s, precisely the years of Carnegies youth and young manhood, the United States experienced not only massive industrialization, mass immigration, and the closing of the frontier but the rapid growth of a modern consumer economy. In contrast to a nineteenth-century landscape of vigorous market exchange regulated by an economic calculus of scarcity, the early twentieth century presented an expansive new world of material abundance where the purchase and accumulation of consumer goods became the new yardstick for measuring achievement.