The interior design and the cover design of this book are intended for and limited to the publishers first print edition of the book and related marketing display purposes. All other use of those designs without the publishers permission is prohibited.

Foreword

A Thousand Stitches is a gift from Constance OKeefe, the author, to Isako Imamura, the widow of Professor Shigeo Imamura (Shig). Shig and Isako had a great impact on Connies life, beginning when she was a graduate student working with Professor Imamura at Michigan State University. After graduation, Connie obtained a teaching position in Japan thanks to Professor Imamura. Thus began her lifelong love of Japan: the country, its people, its history, its language, and its culture.

When Shig died in 1998, Isako asked Connie and two of Shigs other graduate students (Stephanie Vandrick and me) to help her see his memoir published. Isako was committed to telling Shigs storyan anti-war story of a Nisei, Japanese American, who moved with his parents from San Francisco to Japan in 1932 at the age of ten. After serving in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II, Shig spent his life promoting peace through international education and cultural understanding. We three quickly agreed to help Isako and began work on what we called the Shig Project.

In 2001, Shig: The true story of an American Kamikaze: A memoir by Shigeo Imamura was published. Anyone who knew Shig hears his voice in his memoir, a straightforward recollection of his experiences. About this time and with Isakos blessings, Connie began working on a fictionalized version of Shigs story A Thousand Stitches . In the novel two stories are tied together by a senninbari , a belt of a thousand stitches made by a thousand female hands given by wives and sweethearts to Japanese men on their way to war as an amulet: one the main characters story, largely based on Shigs life, and the other a fictionalized story of his high school sweetheart who gave him a senninbari . Connies work began as an extension of the Shig Project. This time, however, she was not the coordinator of the project; rather she was the sole creator.

Connie threw herself into writing the novel with the same intellect, enthusiasm, patience, and attention to detail that she gave to all her work, professional and personal. Building on her extensive knowledge of Japan and its culture and her research for the memoir, she began. A voracious reader since childhood, she read anything she could get her hands on about World War IIera Japan, about fiction writing, and topics closely and peripherally related to the content of the novel. She researched every detail, amassing books on such topics as Japanese cranes, Japanese poetry, the Zero plane, memoirs of Japanese and U.S. soldiers, stories of Japanese civilians, and World War II history books. She joined and built writing communities, in person and online.

When she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2008, she had a draft of the novel and had already sent parts out to several people for comment. She continued to work on the novel as long as possible: checking details, adding and rearranging material, and polishing the prose. During times when she was feeling well, she would walk to the nearby public library several days a week to work there. She was committed to her dream of publishing the novel for Isako and telling Shigs story. She was able to complete the novel before her death on March 19, 2011. During her illness, she asked me if I would see that her novel was published. I was honored and quickly gave her my promise. We agreed that any profits from the novel would go to the Shigeo and Isako Imamura fellowships that Mrs. Imamura endowed: one at Michigan State University and the other at the University of San Francisco.

I am pleased that Connies dream and her gift to Isako are now a reality. In her acknowledgments, Connie graciously thanks many people and notes the joy she found working on the novel and the Shig Project. I add my thanks to those who knew and supported Connie. Also I thank the many, some of whom never met Connie, who have supported and encouraged me on this journey to fulfill my promise to her. With her request asking me to see her novel published, Connie gave me a wonderful gift. I am forever grateful to her for this and much more.

Johnnie Johnson Hafernik

January 8, 2014

Notes About Japanese

Names

When both names are used, Japanese names are presented Western style, with personal names first and family names second.

Orthography and Transliteration

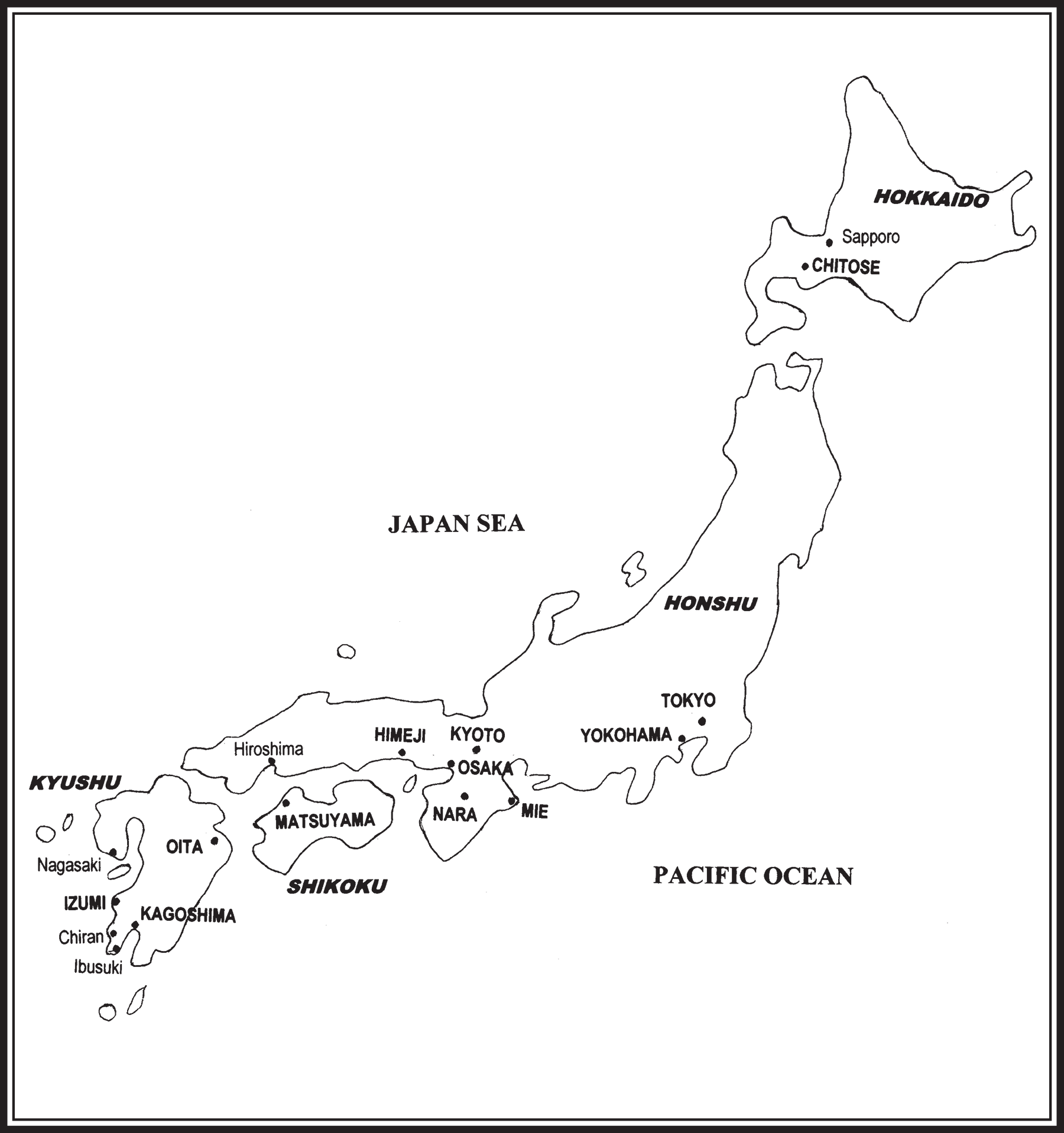

Many Japanese words have long vowels. Various conventions are used to indicate them, with macrons being the most typical. However, that convention is abandoned for very common words such as Tky and saka, which are typically written merely as Tokyo and Osaka. This text takes the same liberties with all Japanese words with long vowels, and numerous personal and place names, most notably the names of the men of the Miyazawa family: Shtar, Tetsutar, and Gentar, appear in the text without any indication of their long vowels. Other personal names (some real, some imaginary, and some mythical) that have lost their macrons in the text include tomo (Tabito, Yakamochi, and Fumimochi) Natsume Sseki, Kkai, Matsuo Bash, Akiko Sat, Sabur Miyakawa, Masao Kat, Amaterasu mikami. Names of places and institutions (some real and some imaginary) that have suffered the same fate include: Hryji Temple, Hokkaid, Honsh, Kysh, the Rykys, Ch University, Kydai (Kyoto University), Tdai (Tokyo University), Kei (University), Tzawa (University Hospital), kaid. The Manysh, Japans great eighth century compilation of famous poems, is another victim, and is referred to in the text simply as the Manyoshu. Other words that are missing long vowels in the text include shch , Shint, tokk, It, Dki no Sakura, tokk, aka-gera.

The sound written with n in Japanese is pronounced m before bilabials such as b and p. Thus, the Tokyo neighborhood, Shinbashi is often rendered in English as Shimbashi (as it is typically pronounced). In this work, words with this combination are therefore transliterated using an m rather than n. Hence, kempeitai rather than kenpeitai, and mompe rather than monpe.

A Note About Aircraft

This story uses the Japanese names for aircraft. The Model 93 Intermediate Trainer (Kugisho Navy Type 93 Intermediate Trainer (K5Y)), the Model 96 fighter (Mitsubishi Navy Type 96 Carrier Fighter (A5M)), and the Zero (Mitsubishi Navy Type 0 Carrier Fighter (A6M)), were, respectively, code-named Willow, Claude, and Zeke by the Allies.