Andrew Osmond - Spirited Away

Here you can read online Andrew Osmond - Spirited Away full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Spirited Away

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Spirited Away: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Spirited Away" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Spirited Away — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Spirited Away" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

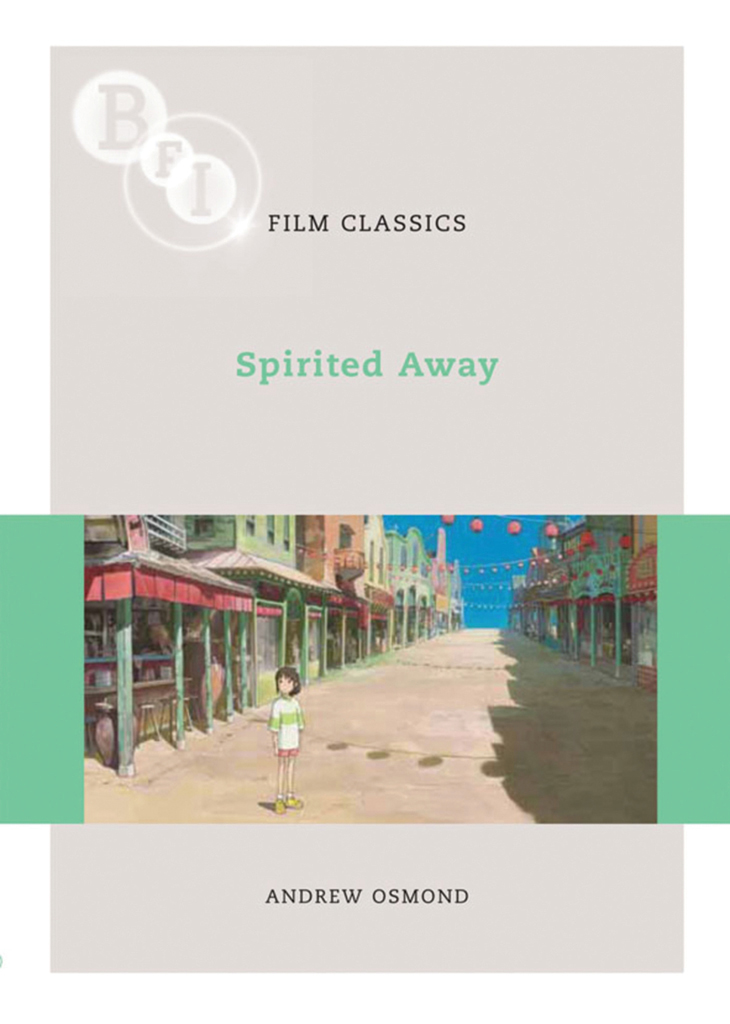

BFI Film Classics

The BFI Film Classics series introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the films classic status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the authors personal response to the film.

For a full list of titles in the series, please visit https://www.bloomsburys.com/uk/series/bfi-film-classics/

Contents

Since this book was fi rst published in 2008, many of the fi lms it mentions, especially those by Miyazaki, have become easy to access. For Anglophone readers interested in further research, I would enthusiastically recommend a superb documentary fi lm on Miyazaki, The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, directed by Mama Sunada in 2013. It is available on British DVD. Another documentary, Never- Ending Man, is available on American Blu-ray and may have a British edition by the time you read this.

There are also two hefty book collections of Miyazakis writings, published in excellent English translations by VIZ Media. The second book, Turning Point, contains interviews which are directly connected to Spirited Away. However, the fi rst book, Starting Point, gives a more rounded and compelling portrait of Miyazaki as an artist.

In summer 2019, Spirited Away had a vibrant new life on the big screen, when it fi nally had an offi cial cinema release in China, a territory which never offi cially screened the fi lm in the 2000s. While the fi lm benefi ted from the USChina trade war of the time, it was gratifying to see how well an eighteen-year-old fi lm could play to cinema audiences.

Many of these viewers, in fact, had seen Spirited Away already, as it had been widely pirated in China following its Japanese release. The South China Morning Post interviewed one Chinese woman going to see the fi lm in the cinema. Shed fi rst watched it as a high school student, with several friends squeezed in front of the computer screen, their minds captivated by 10-year-old Chihiros adventures in what appears to be an abandonedamusement park.

Lovers of animation may see a different pertinence in that park, the magic of the past sidelined in the present. As of writing, the traditionally animated feature is moribund in Hollywood. At least in the multiplex, computer-generated (CG) technology has supplanted fi lms such as Spirited Away, which use evocative drawings to create wonderlands and the Alices who explore them.

Such fi lms are still made in many other countries, however, and Ghibli itself supported one of the best, co-producing Michael Dudok de Wits French-animated The Red Turtle (2016). In this way, Ghibli helped the drawn cartoon feature retain a shadow cultural presence behind the high-tech mainstream, like an old bathhouse coming to life after dark.

Japan now makes the greatest number of traditionally animated cartoon features by far. As of writing, Ghibli is reportedly still in production but has not released an in-house fi lm in several years. As mentioned in this books last chapter, Miyazaki followed Spirited Away with the fi lms like Howls Moving Castle and Ponyo. His most recent release is 2013s The Wind Rises, which marginalises the fantasy whimsy of Spirited Away, while foregrounding the ethos of hard work which this book describes.

A growing number of other Japanese creators are also releasing well-crafted, self-contained animated films. Some feel like specifi c responses to Spirited Away. For example, Mamoru Hosodas 2015film The Boy and the Beast starts like Spirited Away, with another unhappy child whisked to a wonderland. However, the fi lm develops very differently, its story sloshing between the fantasy world and modern Tokyo.

This refl ects a trend in new Japanese animated features to show more of the modern world than Miyazaki would countenance. As of writing, the biggest Japanese blockbusters are by director Makoto Shinkai, a self-confessed Miyazaki fan. Shinkais animated fi lms Your Name (2016) and Weathering with You (2019) both involve traditional Japanese customs and beliefs, and journeys into magic worlds. However, the fi lms are also full of pop songs, fast cuts, city backdrops and social media, all alien to Miyazakis style.

Note

This book would not have been possible without the invaluable help and insights of Yuko Tojo and Ayako Yamashita. I am also indebted to Mike Arnold, Jonathan Clements, Benjamin Ettinger, Marc Hairston, Masumi Hanaoka and Ryoko Toyama. My special thanks to Rebecca Barden of BFI Publishing for giving this book the go-ahead. Finally, my deepest gratitude must go to my parents and family for their love and support.

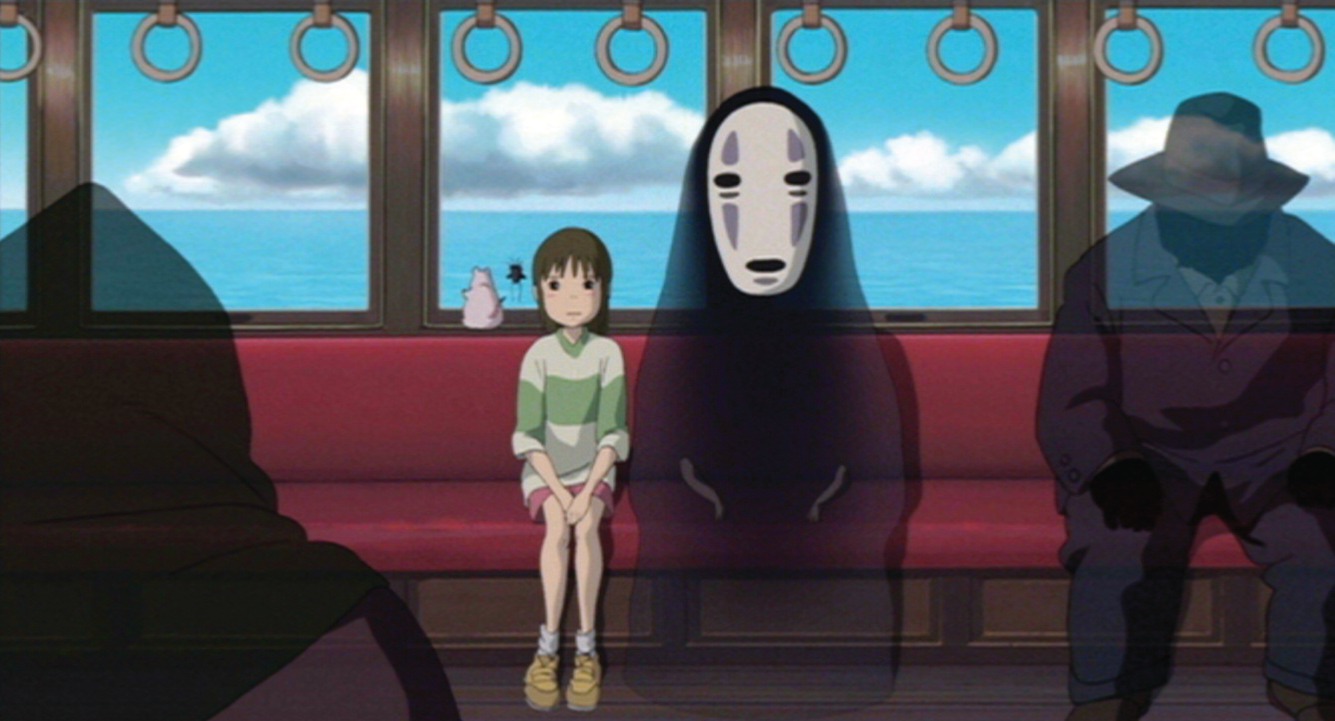

A little girl sits on a train. But this is no normal train; it passes over a flat sea dotted with houses, roads and platforms that poke up from nowhere. The other passengers are shadow-silhouettes. The girl has three companions: a tall black phantom with a Japanese Noh mask and no face, a large white mouse and a fly-like bug with a yellow beak. The child has the grave, determined expression of a weathered adventurer in a childrens story; Alice in Wonderland, perhaps, or The Wizard of Oz. The train stops at a platform, orphaned at sea, where most of the passengers disembark, but the girl and her friends stay on board. As the train moves off, another girl, a silhouette, stands before the platform picket fence and gazes facelessly after.

This is a scene from Spirited Away, the remarkable Japanese animated film directed by Hayao Miyazaki, which has beguiled critics and audiences ever since its release in Japan in 2001. A mysterious, dreamlike cartoon fantasy, it was received differently at home and abroad. In Japan, Spirited Away (or Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi, to give its Japanese name) was a popular blockbuster, the highest-grossing film ever released in the country. In most Western countries, including Britain, Spirited Away was a much-praised but modestly performing film, with an indeterminate, semi-arthouse status. It shared the Golden Bear at the 2002 Berlin Film Festival; the next year it won the Best Animated Feature Academy Award.

On the train

Given the critical and festival plaudits, its ironic that Spirited Away had opened in Japan just as the computer-animated Shrek was breaking records in America. At that time, everyone seemed to be talking about how cartoons were busting out of the childrens ghetto, following the lead of The Simpsons. Western animated films were praised for including split-level, dual-response jokes and references, many designed to fly over childrens heads. Spirited Away stood out because of its lack of obvious split-level humour and also because its most obvious inspirations (to Westerners) werent cartoons or comics but childrens books, especially Alice in Wonderland.

When asked, Miyazaki allowed that Alice might have been an indirect influence, while his supervising animator Masashi Ando indicated that the book inspired one of the main character designs (of the witch character, Yubaba). Miyazaki also specified that he made the film, For the people who used to be ten years old, and the people who are going to be ten years old.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Spirited Away»

Look at similar books to Spirited Away. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Spirited Away and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.