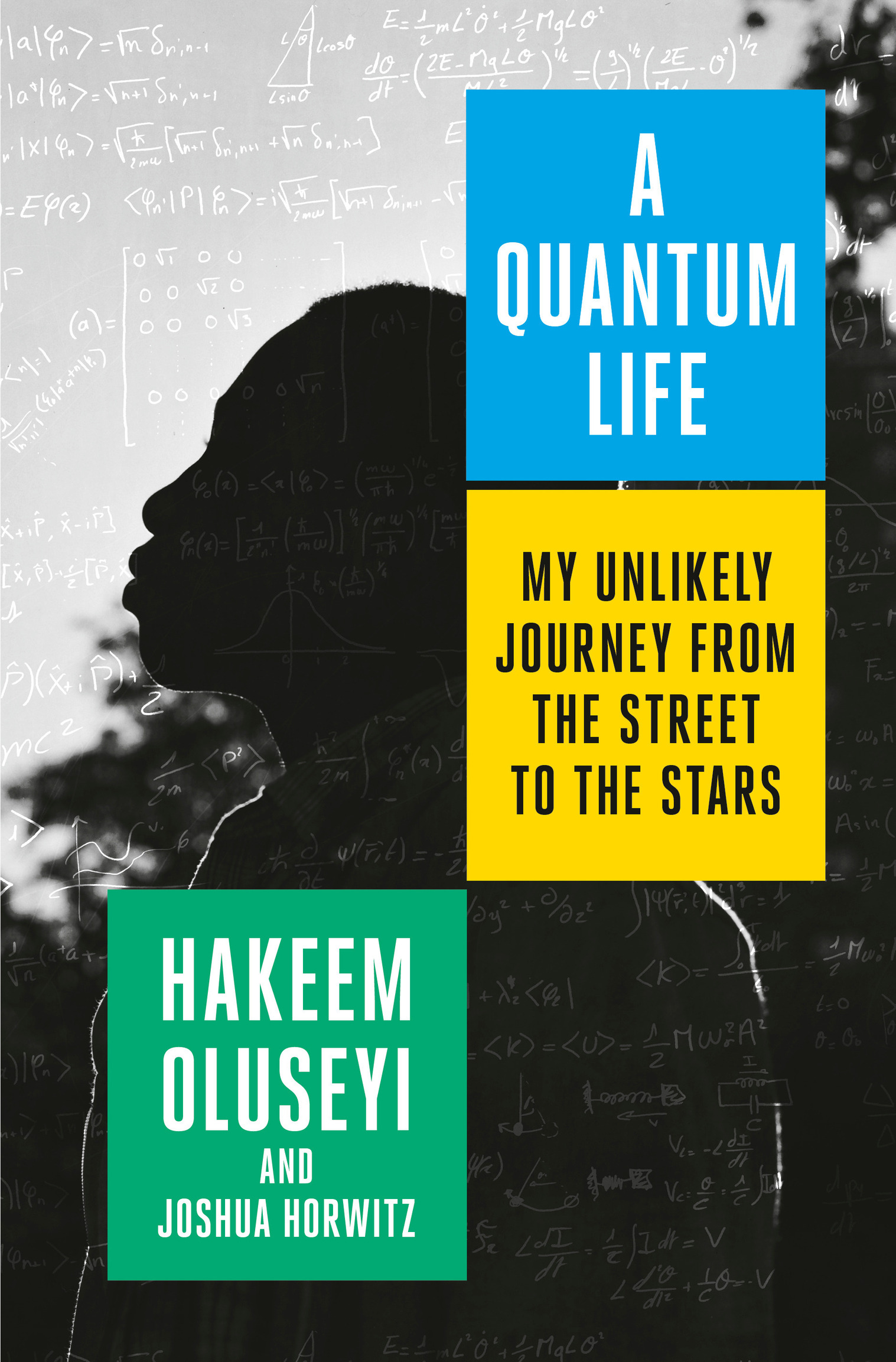

As Ive looked back over my early life, Ive come to recognize that when it comes to personal reminiscence, time and space can bend to conform to the demands of the heart. Nonetheless, after consulting with others who were present at many of the events in this story, Ive re-created scenes and dialogue to the best of my ability. I have changed the names of some of the characters to disguise their identities. While re-creating dialogue, Ive chosen not to reprise the form of address my friends and I used daily growing up: calling dudes niggas and girls bitches and hos. I dont want to normalize self-hate speech for yet another generation of young Black men and women. Otherwise, this memoir is my best effort to truthfully tell the story of my coming of age as a young scientist, and as a young man.

Prologue

S ome years back, a magazine profiled my transformation from James Plummer Jr., a nerdy kid from some of Americas most deeply scarred urban ghettos, to Hakeem Oluseyi, sole Black physicist inside the Science Mission Directorate at NASA. The article ran with the tagline The Gangsta Physicist. The handle stuck, and it followed me wherever I went. I understood that it was an eye-catching tag, that it could open doors and young minds that my science degrees alone could not. But over time I grew to resent it. Gangsta Physicist didnt describe the totality of who I was, how far I traveled, or how hard I worked to get there.

As a bookish kid, I was an easy target in Watts, Houstons Third Ward, and the Ninth Ward of New Orleans. My gangbanger older cousins taught me the rules of the street by the time I was six: who you could look at in the eyes and who you couldnt, how to tell if the dude walking toward you was Crip or Blood, friend or foe. I developed a sixth sense, what I thought of as my dark vision, that let me see all the dirt in my hood: where a deal was going down and where the undercover heat was hiding. The scariest time was after sunset, when the predators came out in force.

I was intrigued by the wider universe, including the night sky. But I couldnt see many stars from the streets where I grew up, what with the big-city lights and the smog. And for the sake of my own survival, I didnt want to be caught staring off into space. Celestial navigation wasnt going to help me find my way home without getting beat up or shaken down. By my early teens, Id adopted a thug persona, walking and talking tough, carrying a gun for protection. But I never joined a gang, and no matter how hard Id tried to straddle the gangsta-nerd divide, I was still mostly a science geek play-acting a thug.

Looking back at my boyhood in the 1970s, I see a frightened child who lived like a feral animal, surviving day by day on hustle and hope. I had a different nickname in those days. They called me The Professor because by the time I was ten years old, I was reading every book I could get my hands on. If anyone had told me Id grow up to be an actual professor at MIT, UC Berkeley, and the University of Cape Town, I wouldnt have believed them. In my hood, that kind of daydreaming was more likely to get you jacked than help you find your next meal or a safe place to sleep indoors.

By any odds and most calculations, I should not be here writing this book. But here I am. Ive learned that no matter how unlikely, anything you imagine for yourself is within the realm of possibility. Its a proven fact of physics. In quantum mechanics, the most improbable of outcomes is called quantum tunneling. If you try to walk through a wall, in all likelihood the wall will win. But theres an infinitesimally small probability that you will find a pathway through the wall. My life has been an oscillating pattern of passing through walls, then walking into the next one and bouncing hard in the opposite direction. Im living proof that our lives are ruled by the laws of quantum, rather than deterministic, physics.

I dont believe in fate, whether written in the stars or anywhere else. I wasnt destined to find a path through the heaviest hoods in America to an elite career in astrophysics. It could have gone either way for me. At any of a dozen junctures in my life, I could have turned left or right, a gun could have gone off in my hand or in someone elses.

My youth traversed a multiverse of possibilities. In one universe, James Plummer Jr. got shot during a drug deal gone bad and died in the streets of Jackson, Mississippi. In another, nonparallel universe, he found his way to a PhD physics program, learned to design rocket-launched telescopes that could photograph the suns invisible light spectrum, and became Professor Hakeem Oluseyi.

None of those namesJames, Hakeem, Professor, Gangsta Physicistforetold my journey through the multiverse. But they remind me, like star trails across the night sky, of the limitless possibilities in this quantum life.

Washington, D.C., 2021

If I told you that a flower bloomed in a dark room, would you trust it?

Kendrick Lamar, Poetic Justice

1

1971: NEW ORLEANS EAST

I was four years old when my family busted apart. What I remember most about that last night together was all the fussing and fighting. When the noise woke us up, my older sister, Bridgette, and I lay in our bed and listened. Bridgette, who was ten, held my hand and tried to soothe me back to sleep. But the shouting just got louder.

I dont know who started the ruckus. Mama and Daddy were always getting into it about this or that, but that night was meaner than usual. It sounded like either Mama had been stepping out on him, like Daddy said, or else that was a filthy lie, like Mama said. By the time Bridgette and I stuck our heads out of our bedroom to look, theyd been hissing and hollering for half an hour.

Just then, Mama picked up a heavy glass ashtray full of butts and threw it at Daddys head. He ducked and the ashtray hit the wall hard. Thats when Daddy punched her. He used to be an amateur boxer, and a pretty good one, according to Aunt Middy. But Id never seen Daddy take a swing at Mama. That night, he hit her square across the side of the head. She dropped like a sock puppet. As soon as she went down, Daddy kneeled beside her and started crying and apologizing and petting her up, saying sweetheart this and sweetheart that.

But Mama always kept score, and she would always rather get even than make up. Daddy begged her to come to bed, but Mama just turned away from him and shook her head no. Bridgette led me to our bedroom and sang me a lazy-voice lullaby to help me get back to sleep. Mama had other ideas. Later that night, when Daddy was sleeping, she fetched a can of lighter fluid from the barbecue and sprayed it on her side of the bed. When she touched her Zippo to the mattress, Daddy thought hed woke up in hell, which I guess he had.

![Johnson - This boy: [a memoir of a childhood]](/uploads/posts/book/185323/thumbs/johnson-this-boy-a-memoir-of-a-childhood.jpg)