Cut copy

The charge levelled at Roy Lichtenstein in the Life magazine article, Is He the Worst Artist in the US? (1964), was that he was no more than a copyist, that his paintings of blown-up comic strips, cheap ads and reproductions are tedious copies of the banal. While the comic-book paintings remain the most notable of his legacy, they are but a small number of works in an oeuvre that spanned fifty years.

To understand Lichtensteins significance, one has to observe the material complexities of his production. While attention to colour was an early occupation, Lichtenstein was ultimately obsessed with form. Despite the starkness of many works, he created a distinctive iconography based on connections between mass culture and the history of art. Rather than being empty duplicates of the original sources, in sampling mustard on bread (Mustard on White 1963, Tate) and Mondrian grids (Non-Objective I 1964, The Eli and Edythe L. Broad Collection, Los Angeles), his work forged a radical ambiguity in which prosaic objects and iconic artworks were reborn. I really dont think that art can be gross and over-simplified and remain art, said Lichtenstein in an interview with John Coplans in 1972, I mean, it must have some subtleties, and it must yield to aesthetic unity, otherwise its not art.

Drawing by seeing

Roy Fox Lichtenstein was born on 27 October 1923, at the Flower Hospital in New York City. His father, Milton, was a real-estate broker who specialised in managing garages and parking structures. Although there was no obvious artistic precedent in terms of the visual arts, his mother Beatrice was a gifted amateur pianist. Lichtensteins fascination with jazz, which began during secondary school at the Franklin School for Boys, where he played piano, clarinet and flute in a small band, was born of his mothers influence. He also sought out live jazz concerts at Staples on 57th Street, Manhattan, and the Apollo Theater in Harlem. Coinciding with this embrace of jazz, Lichtenstein enrolled in Saturday morning watercolour classes at Parsons School of Design, where he painted still lifes and flower arrangements. These classes encouraged him to paint figurative watercolours of Belgrade Lakes in Maine, where he spent two summers.

After graduating from secondary school he attended Reginald Marshs painting class at the Art Students League in New York, where he studied life drawing and Renaissance techniques, such as glazing and underpainting. Marsh espoused a view of art that rejected the European avant-garde art of futurism and cubism, and instead promoted a sentimental realist tradition of depicting American culture: Coney Island in the sun, bourgeois women at the opera, towering cityscapes. Initial attempts by Lichtenstein to assimilate Marshs approach to art, with sketches of bright beaches and boxing matches while at the Art Students League, gave way to a frustration at his teachers anti-European reflex. He had been captivated by Pablo Picasso since the age of fourteen, after purchasing his first art book, Thomas Cravens Modern Art: The Men, the Movements,the Meaning (1934), in which he encountered a reproduction of Girl Before a Mirror 1932. Guernica 1937 also made a strong impact on Lichtenstein, when it was shown at The Museum of Modern Art in 1939 to raise funds for refugees of the Spanish Civil War. Admiration for Picasso, whose work would have an impact on Lichtensteins later paintings, particularly seen in Femme au Chapeau 1962 (Collection of Martin Z. Margulies, Miami) and Frolic 1977 (Private Collection), was at odds with Marshs conservative realism.

In September 1940, with the encouragement of his parents, Lichtenstein left the Art Students League and enrolled in the School of Fine Arts at Ohio State University, one of the few institutions to offer studio degree courses. Here he encountered Hoyt Leon Sherman, an influential teacher who taught a class in drawing based

Americana and abstract expressionism

Between 1943 and 1945, during the Second World War, Lichtenstein undertook active service in the US Army, and was deployed to France, Belgium and Germany. During infantry training at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, in 1944, he enlarged cartoons by William H. Mauldin for Stars and Stripes, the Army newspaper, an early indication of the process he would explore in the 1960s. After being discharged from duty he returned to Ohio State University, completed his BFA degree under the GI Bill, and began work there as a teacher in the School of Fine Arts. The following years, 19461950, were a period of prolific experimentation, during which he produced paintings in the style of Georges Braque, Paul Klee and Picasso, many featuring abstract figures with disproportionate limbs. Few of these works survive. His first group exhibition, in 1948, which included several paintings of this period, was at the Ten Thirty Gallery in Cleveland, Ohio. Here he met gallery assistant Isabel Wilson, whom he married the following year.

In the early 1950s Lichtenstein began to focus on distinctly American subject matter, particularly the frontier, as evident in the works Death of Jane McCrea 1951 and George Washington Crossing the Delaware 1952. The inclination to render aspects of American history was an attempt to make sense of his earlier education at the Art Students League under Reginald Marsh. He also painted several self-portraits as a medieval knight, which were shown together with Despite this minor encouragement in the press, however, sales were poor and as a result he struggled to support his young family, which by 1956 included two infant sons. Reprieve came the following year when he accepted a position as Assistant Professor of Art at the State University of New York at Oswego, where he abandoned American-themed work and embraced abstract expressionism, the style then predominant in New York. When the abstract work was shown at Condon Riley Gallery, Manhattan, in 1959, it received little attention and Lichtenstein grew increasingly frustrated.

Growing despondent in his studio, he produced a series of drawings said to be in response to Willem de Koonings Woman III 19523 (Private Collection), in which a roughly animated figure materialises from a mess of colour.

Pop art?

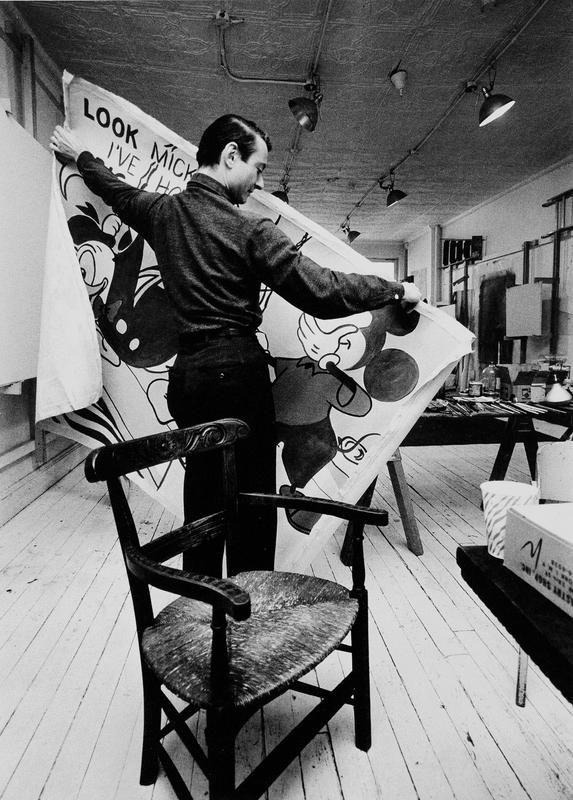

The early 1960s was an especially innovative period for Lichtenstein. Having found an elemental source for his work in comics, he began to develop an industrial painting technique, which combined flat-print areas of solid colour with Benday dots. These are named after American artist and inventor Benjamin Day, who first generated dots when adapting pen drawings for commercial illustration in the late nineteenth century. Lichtenstein says of the process: I am nominally copying, but I am really restating the copied thing in other terms. In doing that, the original acquires a totally different texture. It isnt thick or thin brushstrokes, its dots and flat colors and unyielding lines.

Look Mickey was drawn directly on to canvas with pencil and painted in oil, and differs only slightly from the original source; pencil marks of the initial sketch are clearly visible. The Benday dots, produced using a handmade metal screen and scrub brush, are painted equidistant in two carefully defined areas, Mickeys face and Donalds eyes. Confining the Benday dots to such small areas creates The result is a peculiarly modernist brand of popular art, where the girls outline is compressed to the point where figuration almost disappears and a jigsaw of stark, colourful shapes emerges in its place.