Also by Marilynne Robinson

Fiction

Gilead

Nonfiction

Mother Country

The Death of Adam

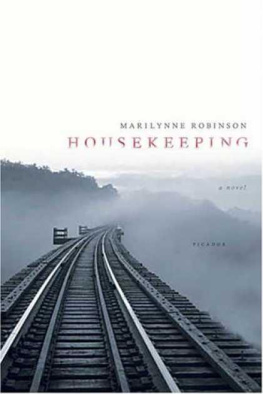

HOUSEKEEPING

HOUSEKEEPING

Marilynne Robinson

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

19 Union Square West, New York 10003

Copyright 1980 by Marilynne Robinson

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Originally published in 1981 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

This reissue, 2005

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Robinson, Marilynne.

Housekeeping / Marilynne Robinson.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-374-17313-5

ISBN-10: 0-374-17313-3

1. Eccentrics and eccentricitiesFiction. 2. MothersDeath-Fiction. 3. GirlsFiction. 4. AuntsFiction. I. Title.

PS 3568.03125 H6 1980

813'.54 19

80024061

www.fsgbooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my husband,

and for James and Joseph, Jody and Joel,

four wonderful boys

HOUSEKEEPING

My name is Ruth. I grew up with my younger sister, Lucille, under the care of my grandmother, Mrs. Sylvia Foster, and when she died, of her sisters-in-law, Misses Lily and Nona Foster, and when they fled, of her daughter, Mrs. Sylvia Fisher. Through all these generations of elders we lived in one house, my grandmothers house, built for her by her husband, Edmund Foster, an employee of the railroad, who escaped this world years before I entered it. It was he who put us down in this unlikely place. He had grown up in the Middle West, in a house dug out of the ground, with windows just at earth level and just at eye level, so that from without, the house was a mere mound, no more a human stronghold than a grave, and from within, the perfect horizontality of the world in that place foreshortened the view so severely that the horizon seemed to circumscribe the sod house and nothing more. So my grandfather began to read what he could find of travel literature, journals of expeditions to the mountains of Africa, to the Alps, the Andes, the Himalayas, the Rockies. He bought a box of colors and copied a magazine lithograph of a Japanese painting of Fujiyama. He painted many more mountains, none of them identifiable, if any of them were real. They were all suave cones or mounds, single or in heaps or clusters, green, brown, or white, depending on the season, but always snowcapped, these caps being pink, white, or gold, depending on the time of day. In one large painting he had put a bell-shaped mountain in the very foreground and covered it with meticulously painted trees, each of which stood out at right angles to the ground, where it grew exactly as the nap stands out on folded plush. Every tree bore bright fruit, and showy birds nested in the boughs, and every fruit and bird was plumb with the warp in the earth. Oversized beasts, spotted and striped, could be seen running unimpeded up the right side and un-hastened down the left. Whether the genius of this painting was ignorance or fancy I never could decide.

One spring my grandfather quit his subterraneous house, walked to the railroad, and took a train west. He told the ticket agent that he wanted to go to the mountains, and the man arranged to have him put off here, which may not have been a malign joke, or a joke at all, since there are mountains, uncountable mountains, and where there are not mountains there are hills. The terrain on which the town itself is built is relatively level, having once belonged to the lake. It seems there was a time when the dimensions of things modified themselves, leaving a number of puzzling margins, as between the mountains as they must have been and the mountains as they are now, or between the lake as it once was and the lake as it is now. Sometimes in the spring the old lake will return. One will open a cellar door to wading boots floating tallowy soles up and planks and buckets bumping at the threshold, the stairway gone from sight after the second step. The earth will brim, the soil will become mud and then silty water, and the grass will stand in chill water to its tips. Our house was at the edge of town on a little hill, so we rarely had more than a black pool in our cellar, with a few skeletal insects skidding around on it. A narrow pond would form in the orchard, water clear as air covering grass and black leaves and fallen branches, all around it black leaves and drenched grass and fallen branches, and on it, slight as an image in an eye, sky, clouds, trees, our hovering faces and our cold hands.

My grandfather had a job with the railroad by the time he reached his stop. It seems he was befriended by a conductor of more than ordinary influence. The job was not an especially good one. He was a watchman, or perhaps a signalman. At any rate, he went to work at nightfall and walked around until dawn, carrying a lamp. But he was a dutiful and industrious worker, and bound to rise. In no more than a decade he was supervising the loading and unloading of livestock and freight, and in another six years he was assistant to the stationmaster. He held this post for two years, when, as he was returning from some business in Spokane, his mortal and professional careers ended in a spectacular derailment.

Though it was reported in newspapers as far away as Denver and St. Paul, it was not, strictly speaking, spectacular, because no one saw it happen. The disaster took place midway through a moonless night. The train, which was black and sleek and elegant, and was called the Fireball, had pulled more than halfway across the bridge when the engine nosed over toward the lake and then the rest of the train slid after it into the water like a weasel sliding off a rock. A porter and a waiter who were standing at the railing at the rear of the caboose discussing personal matters (they were distantly related) survived, but they were not really witnesses in any sense, for the equally sound reasons that the darkness was impenetrable to any eye and that they had been standing at the end of the train looking back.

People came down to the waters edge, carrying lamps. Most of them stood on the shore, where in time they built a fire. But some of the taller boys and younger men walked out on the railroad bridge with ropes and lanterns. Two or three covered themselves with black grease and tied themselves up in rope harnesses, and the others lowered them down into the water at the place where the porter and the waiter thought the train must have disappeared. After two minutes timed on a stopwatch, the ropes were pulled in again and the divers walked stiff-legged up the pilings, were freed from their ropes and wrapped in blankets. The water was perilously cold.

Till it was dawn the divers swung down from the bridge and walked, or were dragged, up again. A suitcase, a seat cushion, and a lettuce were all they retrieved. Some of the divers remembered pushing past debris as they swam down into the water, but the debris must have sunk again, or drifted away in the dark. By the time they stopped hoping to find passengers, there was nothing else to be saved, no relics but three, and one of them perishable. They began to speculate that this was not after all the place where the train left the bridge. There were questions about how the train would move through the water. Would it sink like a stone despite its speed, or slide like an eel despite its weight? If it did leave the tracks here, perhaps it came to rest a hundred feet ahead. Or again it might have rolled or slid when it struck bottom, since the bridge pilings were set in the crest of a chain of flooded hills, which on one side formed the wall of a broad valley (there was another chain of hills twenty miles north, some of them islands) and on the other side fell away in cliffs. Apparently these hills were the bank of still another lake, and were made of some brittle stone which had been mined by the water and fallen sheerly away. If the train had gone over on the south side (the testimony of the porter and the waiter was that it had, but by this time they were credited very little) and had slid or rolled once or twice, it might have fallen again, farther and much longer.

Next page