Copyright 2014 Margaret Willes

Published with acknowledgement to the Marc Fitch Fund.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of pictures reproduced in this book. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful to be notified of corrections for future editions.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Adobe Caslon Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Willes, Margaret.

The gardens of the British working class / Margaret Willes.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-18784-7 (alk. paper)

1. GardensGreat BritainHistory. 2. GardeningGreat BritainHistory. 3. Working classDwellingsGreat BritainHistory. I. Title.

SB451.36.G7W54 2014

635dc23

2013041145

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

I Poplar Cottage at the Weald and Downland Museum. The cottage, brought from Washington in Sussex, dates from the early to mid-seventeenth century and probably belonged to a landless husbandman. The garden has been recreated to show how it was given over to practical plants, cultivated in beds separated by narrow paths, which would be used in the kitchen, the medicine chest, and for dyeing and brewing.

II Bayleaf Farmstead at the Weald and Downland Museum. This timber-framed hall house, dating from the 1540s, was brought from Chiddingstone in Kent. It would originally have been the home of a yeoman farmer. Its extensive garden of vegetables, herbs and fruit is protected by a fence of intertwined hazel branches.

III Bee skeps of plaited straw in the garden of Bayleaf Farmstead. Hives are depicted in early gardening books, such as Thomas Hill's Gardeners Labyrinth, standing in shelters like this to protect them from the wind and rain.

IV The back garden of a seventeenth-century house from the Sussex village of Walderton, which is now at the Weald and Downland Museum. In the centre is one of the beds for the cultivation of vegetables and salad herbs, while the wooden planks on the right protect a bed for the cultivation of pompions, or pumpkins.

V Sir Bernard de Gomme's plan, in ink and watercolour, of the citadel and town of Plymouth in Devon in 1672. On the outskirts of the town, gardens are shown; some of them were clearly detached grounds.

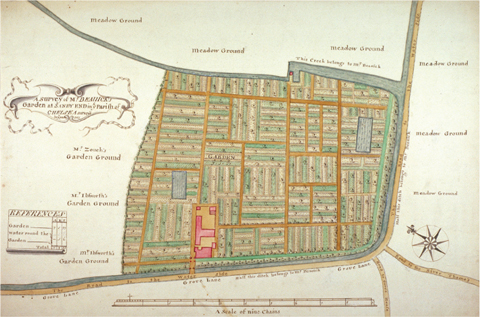

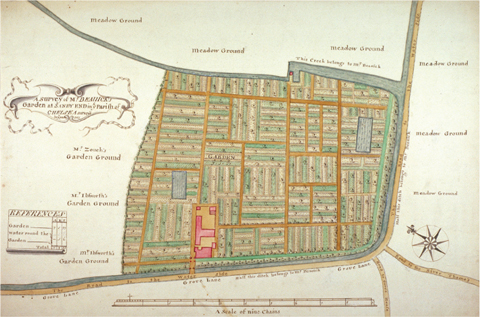

VI Mr Beawick's market garden near Grove Lane in Chelsea, from a survey made in 1744. The garden was just over seven acres in area, laid out in strips with walkways and two dipping pools. The locality was particularly favourable for market gardening, with sandy soil and a surrounding creek to supply water.

VII Watercolour by C.H. Mathews of Kingsland Road in Hackney. The artist painted the picture in 1852, but it shows how the area would have looked at the beginning of the nineteenth century when the market gardens, on the right, were giving way to terraces of houses constructed with the bricks being manufactured on the left.

VIII A watercolour by George Johann Scharf of Unity Place in Woolwich, 1825. The tiny front gardens are enclosed behind picket fences, and pots of flowers are shown at some of the windows. Estate agents would now describe these as bijou urban cottages; in the Regency period they would have been the homes of the artisans and lower middle classes.

IX King's Cross, London: The Great Dust-Heap, next to Battle Bridge and the Smallpox Hospital, a watercolour by E.H. Dixon, 1837. The heap, which evokes the enterprise of the Golden Dustman in Charles Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, was finally removed in 1848 to make way for the railway terminus of King's Cross. Allotments can be seen cheek by jowl with the rubbish.

X Three different varieties of pansies, from Joseph Harrison's Floricultural Cabinet, from about 1835. Pansies had become the object of interest to florists, who developed the heart-shaped flower of the wild pansy, or heartsease, into an increasingly stylised circular form.

XI The dahlia made its first appearance in British gardens in the early nineteenth century and proved a sensational success. The ideal for florists was the ball shape, with a sphere of geometrically arranged petals. These were known as show dahlias or fancy dahlias. This chromolithograph made around 1870 shows the Dr Frampton dahlia.

XII A gardener scything in a grand formal garden in the 1860s.

XIII A cottage garden depicted in a watercolour by Myles Birket Foster. Unlike similar images from the Victorian period, this has no romantic connotations, showing an elderly lady tending her vegetable patch, with washing drying over a dilapidated fence.

Next page