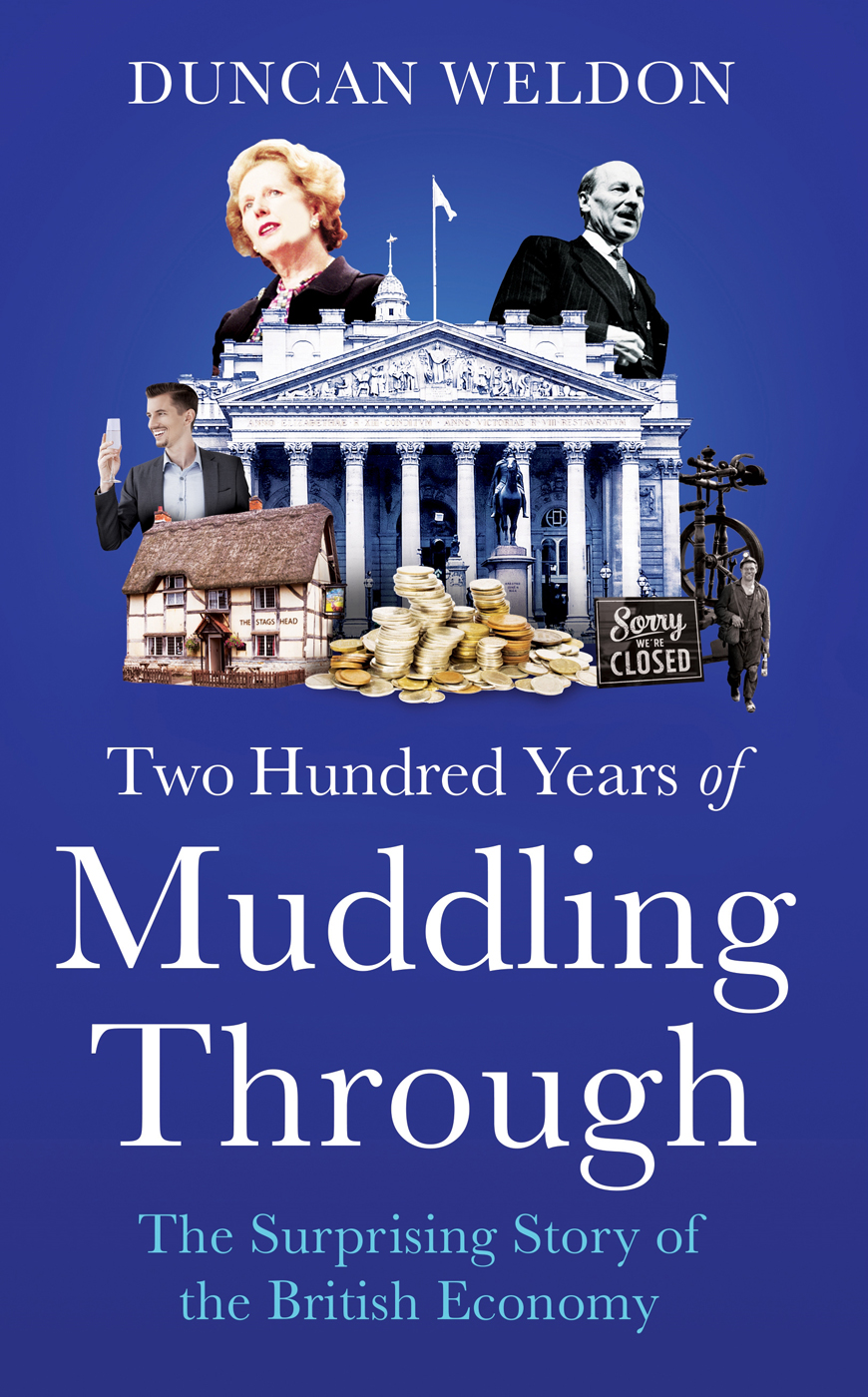

Duncan Weldon - Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through

Here you can read online Duncan Weldon - Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Little, Brown Book Group, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through

- Author:

- Publisher:Little, Brown Book Group

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Published by Little, Brown

ISBN: 978-1-4087-1315-0

Copyright Duncan Weldon 2021

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Little, Brown

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.littlebrown.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

For Julia, Louise and Josie

Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-elected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.

Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

There is a very famous, and very old, Irish joke about a man asked for directions by a tourist and responding Well, if I was you, I wouldnt start from here. While the joke may not have people rolling in the aisles it is a pithier way of expressing what Marx said. Both are making the same point: people do not get to choose where they begin, and that insight, whilst simple, is too often forgotten when discussing the economy and politics.

This is a book about how the British economy got to where it is today. The economy on the eve of the COVID-19 recession was strangely paradoxical: at the same time both one of the worlds most successful and one of Europes laggards. In terms of GDP per head Britain is a world leader but productivity levels (even before the last decade) are abysmally low compared to its advanced economy peers. The country contains some of the EUs richest areas but also some which are more akin to southern Europe than to Germany or France. It is really not too much of an exaggeration to describe the UK, in economic terms, as Portugal but with Singapore in the bottom corner.

Economic history helps to explain how that happened. If this book has one theme, it is that path dependency matters.

Path dependency is perhaps best thought of as the idea that the route one took to arrive somewhere is just as important as the destination. In the social sciences (and especially in economic history) this notion can be crucial. Or, to put it another way, the past and history matter and sometimes in ways which, like the man advising the tourist, are not especially helpful in the present.

The idea has been widely applied in technological history and perhaps the most famous example that many economists instinctively reach for is the design of the standard QWERTY keyboard.

As traditionally told, the story runs something like this. When the typewriter was first invented in the 1860s, by Milwaukee-based printer and newspaper man Christopher Latham Sholes, he naturally laid out the keys in alphabetical order, and whilst that may look odd to modern eyes it intuitively makes a lot more sense than starting with the Q and then moving on to the W the E and the R.

But his early models suffered from mechanical problems and a tendency to jam if keys that lay next to each other were hit in rapid succession. So by the time he filed his patent in 1878 Sholes had rearranged the layout to get round this problem. Keys likely to be hit one after the other regularly were placed at opposite ends of the keyboard, and whilst this slowed down typing speed, that was a feature not a bug of the design. The whole point was to slow the process and prevent the expensive machines from constantly jamming.

Sholes went into business with gun manufacturer Remington, which given the end of the US Civil War in 1865, was presumably looking for new lines of business. By 1893 the five largest typewriter makers had all adopted the QWERTY standard and history was set in place.

Of course a modern computer does not suffer from the same mechanical faults as a nineteenth-century typewriter. Indeed, the argument goes, those mechanical faults had actually been eliminated on typewriters by the 1920s.

In 1936 August Dvorak patented an alternative layout, which in tests by the US Navy in 1944 (at a time when the ability to produce reports rapidly really mattered) apparently led to quicker typing. But despite a better design being available and despite the original rationale for the adoption of QWERTY no longer holding, it is still the industry benchmark.

By coming to market first the QWERTY board established a standard. Individual typists, who had trained on a QWERTY, were reluctant to switch to a new layout, and manufacturers, seeing no demand for alternatives, were happy to keep putting them out. The less efficient technology became baked in.

Or that is how the traditional story goes, anyway. And it serves very well indeed to demonstrate a practical application of the idea of path dependency. Sadly, like many good stories, it may not be entirely true: the Dvorak system has its sceptics. But whatever the actual truth of most economists favourite example of the phenomenon, it remains very useful. And path dependency can be applied far more widely than in just technological history.

It certainly appears in what might be termed economic geography. Ever since Adam Smith, economists have long noted the tendency for businesses to cluster. If, say, a thriving printing industry has developed in any one town or city it makes sense for other printers to open their businesses in the same place the local labour market will contain skilled printers and the necessary suppliers of paper and ink will already be available. The reason why the particular industry originally grew up in that locale maybe because of the presence of a certain skillset in the local jobs market, the availability of certain raw materials or something else entirely may matter less than the fact that it happened.

One reason why the American publishing industry has historically been centred on New York is simply because it was where the fast boats arrived from the United Kingdom in the nineteenth century. This meant that the most recent Charles Dickens novels (in his day a writer with as much box office potential in the US as in Britain) hit New York first, where the local printers showing a very poor regard for intellectual property rights would pirate and reprint the text for the American market. (Concerns about the cross-border enforcement of copyright rules are truly nothing new.) Cross-Atlantic shipping schedules no longer have any relevance for the industry, but, having established itself in New York, once it was there it was there.

A depressing 2015 study by the think tank Centre for Cities looked at the growth and performance of British cities between 1911 and 2011. One important conclusion was that the proportion of knowledge workers in a citys workforce was a significant determinant of a citys prospects in 2011. And the single most important factor explaining the number of knowledge workers in 2011 was how many knowledge workers had been present in 1911. The reason, the authors reckon, that Wigan did not have a booming tech centre in 2011 was that it was an industrial mill town in 1911. Central Manchester by contrast already had a core of highly skilled service sector workers a century before. History matters.

Another example is what some economists term hysteresis effects. Derived from the Greek for that which comes later, hysteresis effects are simple effects which persist well after the initial catalyst or cause is gone. The two most common examples cited are in the labour market and international trade. It may be for example that a rise in the value of the pound makes certain British exports uncompetitive overseas and the firms in this industry respond by cutting back production and jobs. However if, a few years later, the pound falls in value and British exports are once again internationally competitive then production and employment may not return to their old levels. During the period of a highly priced pound and increased unemployment, British workers may have seen their skills degrade and other, foreign, firms may have taken up their market share. A rising pound thus may increase unemployment in one sector but the pound returning to its original level not eliminate the effect. This was the case in the mid- to late 1980s when a strong pound acted as catalyst to the decline of British manufacturing jobs. The weaker pound of the early 1990s failed to spur re-employment.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through»

Look at similar books to Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.