Preface

Ralph Dickson was a gifted storyteller. (I use pseudonyms unless otherwise noted to protect the privacy of research participants.) He had lost his wife to cancer two months before I arrived in Okinawa, and while friends spoke fondly of him, no one volunteered to introduce him to me as a potential research participant. Struggling with grief and depression, he spent his evenings drinking at local bars and strumming his guitar. Friends from the village often had to help him home at night. When we finally met, it was at a dinner party hosted by a mutual friend. Learning of my research and interest in Okinawan history and culture, he invited my husband and me to join him on a bike tour of Yagaji Island the following weekend. Soon we were meeting on a regular basis, exploring historical sites in northern Okinawa on bicycle and in his beat-up Daihatsu pickup truck, while he spoke sentimentally of postwar Okinawa in his distinctive Oklahoma drawl.

Ralph had met his wife, Chiemi, at a village festival in Kin in 1967. He was unclear about her role at the gathering. Was she attending the festival with other town residents, or was she working at the club the Americans convened to after it began to rain? Upon inquiring, he was told, That one, she doesnt go out with anybody. She does her job, and she does what has to be done, but she doesnt date Okinawans or Japanese or Americans. She doesnt date, period. Despite the warning, he approached her. The two gradually developed a friendship, and in 1969, they moved in together. Eventually, they were married. In 1978, Ralph retired from the navy and took a civilian position on Camp Schwab. Chiemis uncle, a wealthy landowner and businessman, helped the couple buy land associated with a pineapple cannery he owned in Nakijin, and they moved into the top floor of the abandoned factory.

Visiting Ralphs home, one climbed a rusted steel staircase bolted to the outside of the building and then entered a drafty hallway with high unfinished ceilings. To the right, sliding Plexiglas doors hid tatami rooms used for sleeping. To the left, a door opened into a large room containing the family altar and a low table surrounded by floor cushions. The kitchen and makeshift bathroom remained unfinished. Ralphs house was considered strange by his American and Okinawan friends alike, and this seemed to add to the common perception of him as a strange individual, neither Okinawan nor American. Neighbors living in the vicinity were initially against the idea of having an American military man for a neighbor. But after twenty-two years, Ralph had become a fixture in the small mountain settlement, despite his continuing difficulty with Japanese.

RALPH: Its a nice place to live. Its quiet. Everybody knows everybody, and knows everybodys business, but they dont get too personal with you.

AUTHOR: So you dont feel like a gaijin [foreigner]?

RALPH: No, I feel just like one of them. I go on all the old-folks trips, and I belong to the local gate ball team. One time, the mayor of the settlement told me, Yeah, Ralph-san, youre a gaijin, but youre our gaijin.

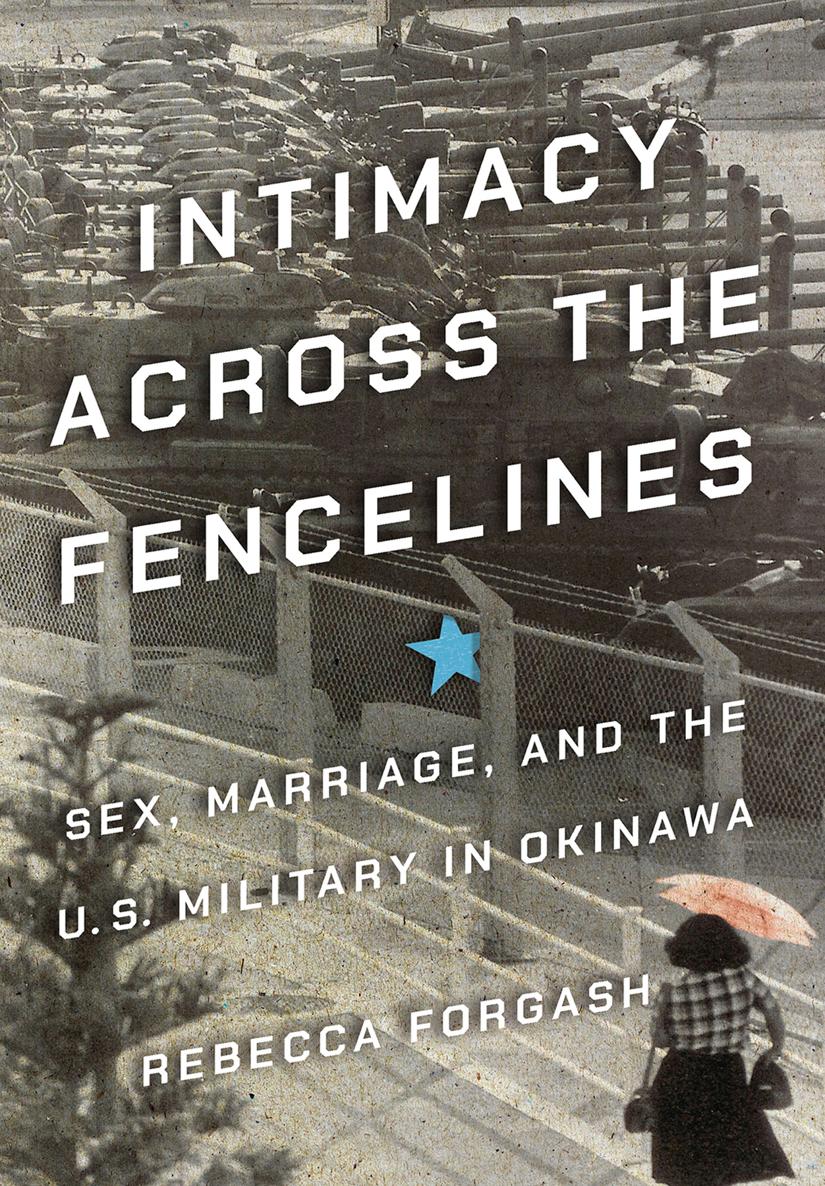

Ralphs stories of living across Okinawas military fencelines for thirty years were fascinating. What was his and Chiemis life like, given the conspicuous nature of intimate relationships between U.S. military men and Okinawan women? What sacrifices had each made, and what benefits did they enjoy due to their relationship? Did Okinawan family and neighbors truly perceive Ralph as one of them, as he believed? This is a book of stories, stories of men and women like Ralph and Chiemi, living in unusual, hybrid, and often difficult circumstances due to their symbolic association with war and American empire. Their stories reflect the larger historical, economic, and social contexts of postwar and postreversion Okinawa, but the stories also structure that reality, rendering it identifiable, understandable, and livable. They are therefore a powerful window on the experiences of men and women in Okinawa at a variety of levels.

My own interest in intimate interactions and relationships between Okinawan women and U.S. military men began nearly twenty years ago. At the time, I had little firsthand knowledge of military life, although a respected uncle previously stationed in Okinawa had shared intriguing stories about living off base, participating in community festivals, and swimming and shelling on isolated beaches. Such idyllic-sounding experiences contrasted sharply with the darker images of U.S. military occupation I had encountered while researching a masters thesis on the U.S. military presence in Haiti during the early twentieth century. The dissonance sparked my interest in the history of U.S. expansion, the variety of experiences of U.S. military personnel abroad, and the views of local people in communities that surround U.S. bases. Inspired by my uncles stories, I took a teaching position at a language school in Japans Hiroshima Prefecture. My employers were an international married couple, an American man and his Japanese wife. Borrowing the capital from her parents, they had opened two successful English language schools. The husband contributed a foreign face, an American accent, and seemingly boundless enthusiasm, while the wife ran the business and handled communications with students and their families. For her, I became a confidant and interpreter of the often-mystifying behaviors of her American husband. Through whispered conversations, I learned of the excitement, confusion, and tension that pervade intimate relationships between American men and Japanese women. When their marriage broke up, I heard about the whole painful ordeal.

Developing a research proposal to study intimate international relationships, I decided on Okinawa as a field site, with an estimated twenty-seven thousand U.S. troops and consistently high rates of international marriage. Like residents of Hiroshima, Okinawans had suffered unimaginable losses during World War II. Colonized by Japan during the late nineteenth century, sacrificed in order to forestall an American invasion of the homeland, and host today to more than 70 percent of the U.S. military installations in Japan, Okinawa is at the center of the U.S.-Japan security alliance and the antiwar and antibase peace movements. Against this backdrop, sexual and romantic intimacy between local people and U.S. military personnel is unavoidably political.

The individuals appearing in this book are diverse, reflecting the heterogeneous makeup of their communities of origin and their communities of residence, whether small villages on Okinawas Motobu peninsula, large military housing areas in central Okinawa, or the transnational community of U.S. military personnel and families, moving back and forth between duty stations in Japan, Hawaii, California, Virginia, and North Carolina. Their stories are also varied, expressed through distinctive speech patterns, colorful turns of phrase, details mentioned versus those left out, and emotions conveyed through tone, emphasis, or silence. I have been drawn to the richly detailed content and delivery of these stories. I worry that I might not be able to do them justice. At the end of nearly twenty years of research and writing, I hope that readers will look beyond the weaknesses of my writing and perspective to appreciate the power and richness of these stories and their narrators.