Copyright 2023 by Dan Berger

Cover design by Ann Kirchner

Cover images The Laundry Room / stocksy.com; Good dreams - Studio / Shutterstock.com; Moremar / Shutterstock.com; Itsmesimon / Shutterstock.com

Cover copyright 2023 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: January 2023

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Berger, Dan, 1981- author.

Title: Stayed on freedom: the long history of black power through one familys journey / Dan Berger.

Description: New York: Basic Books, 2023. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022037502 | ISBN 9781541675360 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781541675377 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Black powerUnited StatesHistory20th century. | African AmericansPolitics and government20th century. | Simmons, Zoharah, 1944- | Simmons, Michael, 1945- | Simmons family. | African American political activistsBiography. | African American civil rights workersBiography. | Civil rights movementsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | African AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC E185.615 .B455 2023 | DDC 323.1196/073dc23/eng/20220823

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022037502

ISBNs: 9781541675360 (hardcover), 9781541675377 (ebook)

E3-20221208-JV-NF-ORI

For Aishah and Julian, catalysts of an ever-expanding freedom journey

Look. How lovely it is, this thing we have donetogether.

Toni Morrison

2000

Every student loves a guest speaker. And the history class I took my freshman year of college had some great ones. There was the Vietnam War veteran who became an anti-war leader, spied on and shot at by the government he once served. There was the folk singer who performed ballads of strife and struggle. It was the only class I looked forward to that semester.

The guest speaker who would most change my life was a professor. She was a new instructor at the University of Florida, having started there that year. She was not a history professor. In fact, she didnt even speak about her scholarship. Faith and marriage had given her the name Zoharah Simmons, though she was born Gwen Robinson. And thirty-five years previously, she had been a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Her involvement in the civil rights movement had led her to put a two-and-a-half-decade pause on her college studies.

Her hair braided and pulled back, bright red lipstick visible from halfway back in the lecture hall, she began to speak. I cannot, in all honesty, remember what she said that day. She probably mentioned that she had been raised by her grandmother, who had been raised by her grandmother, an enslaved woman. She might have mentioned her first political act: an unplanned sit-in on a Memphis bus she did as a teenager after white employers refused to hire her for the middle-class jobs she was raised to desire. Regardless of the specifics, more than twenty years later, I remember feeling enthralled. To my surprise, she was teaching in the Religion Departmenta field far removed from my interests at the time. Nevertheless, the following year, I enrolled in her Race, Religion, and Rebellion class. We read about the ways messianic faith and political protest comingled in African American history, from the nineteenth-century prophecies of abolitionists Nat Turner and David Walker to the ecumenical liberation theology of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and the larger civil rights movement. Along the way, Dr. Simmons revealed tidbits of her Baptist upbringing, her time in the Nation of Islam, and her embrace of Islamic mysticism.

Outside of class, Zoharahas she invited me to call herdrew on her movement history as a faculty advisor to the campus activism I was doing against racism and for worker rights. Zoharah introduced me to the concept of Black Power. Pointing to her time as one of the only woman project directors of Mississippi Freedom Summer, she described Black Power as a response to the feeling of inferiority and helplessness Black people expressed under segregation. She described the motivations plainly: Black people needed to see one another as leaders, thinkers, and doers. Such self-assured affirmations of power were necessary to do away with decades of segregation and terrorism. Whats more, she said in her lilting Tennessee accent, Black Power was a call for white people to confront racism at its source in institutions created and led by white people. Rather than division, Black Power pursued a coalitional strategy of organized constituencies pursuing social change.

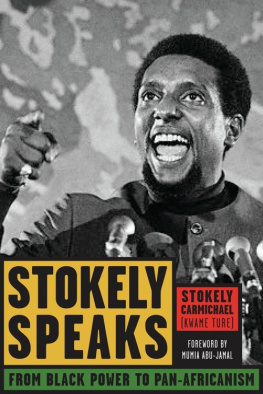

I was shook. As she explained it, Black Power offered a plan of actioneven for a white kid from the suburbs. I rushed to read what I could on the civil rights movement, disappointed to find that many historians associated Black Power with Stokely Carmichael or the Black Panther Party but dismissed the Atlanta Project of SNCC that Zoharah had codirected, where the call for Black Power originated, as an aberration. If her story was true, their story was at best incomplete.

That summer, I drove with several friends to Philadelphia to protest the Republican National Convention. We went to meetings at the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), a Quaker peace and justice organization whose headquarters was blocks from city hall. Before coming to the University of Florida, Zoharah had spent two decades on staff at the AFSC doing everything from investigating government surveillance to leading international human rights delegations. Her ex-husband, Michael, whom I would meet a few years later, still worked there. They came to the AFSC as part of a cohort of 1960s radicals who looked to make social change their avocationBlack Powers long march through various institutions and across the planet.

2010

Dan, what are you doing here? The smooth baritone voice inquired behind me. I was surprised, for I was coming out of my own apartment building, where I had lived for almost two years, so none of the residents would be startled by my presence. And my surprise grew when I saw who was asking. Michael?! I half-yelled, in bewildered delight. You live in Hungary! What are you doing here? We moved to the porch and began to catch up, Michael with a backward Kangol hat and unflappable soul aesthetic, puffing on a cigarillo.

Michael Simmons grew up in a two-bedroom house about four miles from my two-bedroom apartment in West Philadelphia, in a part of the city that some called Brewerytown but that he lovingly called Norf Philly. Michaels stepfather had recently passed away, and Michael was staying in the family home, as he always did when he was in town from Budapest. But today he was in West Philly paying a social visit: it turns out that my downstairs neighbors were his niece and nephew. Their Arabic names owed to the fact that their parents, Michaels brother and former sister-in-law, had been in the Nation of Islam. My ongoing connection to the Simmons family was larger than I realized.