Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by Bruce D. Heald, PhD

All rights reserved

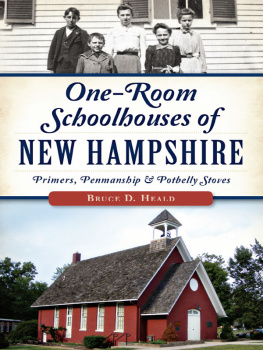

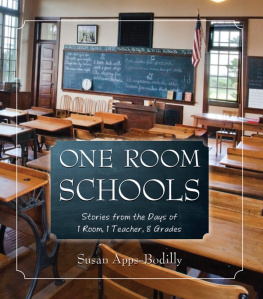

Front cover, top: Bog School in Campton, New Hampshire. Photo courtesy of the New Hampshire Historical Society; bottom: Little Red Schoolhouse. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, contributor Joscinklin.

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62585.054.6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Heald, Bruce D., 1935

One-room schoolhouses of New Hampshire : primers, penmanship & potbelly stoves / Bruce D. Heald ; foreword by Steve Taylor.

pages cm -- (Landmarks)

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-523-3 (paperback)

1. Rural schools--New Hampshire. 2. Public schools--New Hampshire. I. Title.

LB1567.H43 2014

371.009173409742--dc23

2014022663

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Foreword

Few aspects of New Hampshire history engender as much nostalgia and curiosity as the district schools, which in their heyday numbered in the thousands and were extremely important parts of community life in addition to their primary roles as providers of basic elementary education to the states young people.

In this work, we find a carefully researched account of how the state and its people struggled to build an educational system that would serve every child, a radical New World idea that, as it spread throughout colonial America, would become a vital element in the eventual success and strength of our democratic society.

Bruce Heald captures both the nuts and bolts of the district school system and the broader cultural and philosophical issues that surrounded the institution as it evolved over nearly three centuries of time. We will recognize many concerns that prevailed long ago in the continual debates that mark educational policymaking at the local and state levels in New Hampshire today.

As the number of people who can count attendance at a one- or two-room district school as part of their lifes story continues to decline, this volume affords us a solid record of how these schools came to be, how they functioned and what their enduring legacy is. As a product of New Hampshire district schools, I greatly value this bringing together of facts and data heretofore scattered across the states landscape.

STEPHEN H. TAYLOR

Meriden, New Hampshire

Acknowledgements

Norman Alkinson; Ashland Historical Society; George Bush; Colbrook Academy; Concord Public School; Lorenca Consuelo; Coos County Teachers Association; Craydon Village School; Farmington Historical Society; James M. Greenwood; Deborah Herrington; Frank A. Hill, Holderness Historical Society; Roger Kelley; Laconia Historical Society; Lee Historical Society; Littleton Historical Society; Meredith Historical Society; Ruth Moulton; Moultonborough Historical Society; New Hampshire Grange; New Hampshire legislature; North Parsonsfield, Maine Historical Society; Hobart Pillsbury; Plymouth State University; William F. Robinson; Dr. Charles C. Rounds; Sandwich Historical Society; Frank N. Scott; Jonathan Smith; and Stephen Taylor.

Introduction

Learning was widespread in colonial New Hampshire. Colonial New England Protestants used the Bible faithfully in their early education for the preparation of the moral salvation of the youth.

Parents and communities know well that proper formation in the educational development is most essential in preparing sons and daughters for a productive, successful life. Most important was good citizenship, the proper preparation in the three Rs and the general principals of law, commerce, money and government.

Daniel Webster wrote the following regarding childhood education practices in the New World: For America in her infancy to adopt the maxims of the Old World would be to stamp the wrinkles of old age upon the bloom of youth, and to plant the seed of decay in a vigorous cradlelet the first word he lisps be Washington. The national character is not yet formed.

Historian/author Lorenca Consuelo Rosal presented the state of childrens educations when America was first settled: When the first European settlers arrived in New Hampshire, there were no teachers to instruct their children. Most settlers did not see a need for such instruction. Timbering, fishing, farming, building, sawmilling, candle making, spinning, weaving and sewing were the only skills needed for survival. These skills could be taught at home.

The basic education took place in the district school, which was organized, supervised and financed via local taxation, tuition and what other revenue was available through local and state aid. The district system had become prevalent in New Hampshire during the second half of the eighteenth century. This growth was most apparent as population dispersed outward from towns and outlying neighborhoods demanded control over their schools.

The schools were identified in the local school (town) reports by numbers only, due to the multiplicity of school district numbers, which were assigned to neighborhood schools in each town. The district school was often too small to accommodate the increasing number of scholars who attended during the winter months, when farm work slackened. The location for the district school was most often too small and undesirable. In some instances, old schools in a district were replaced by new buildings, and sometimes, a district formed a union with another town.

Within the one-room grammar school, childrens home life diversityvariance in the availability of supplies, parents support salaries and parents working conditionschallenged our teachers. Most teachers attempted to group the children into classes based on the level of supplies that were available from home. Thus, each child would bring to school whatever the family happened to have, which were often books that had been passed down by his or her parents.

In the face of these challenges, many teachers did well, but others performed quite poorly. There was no possible way to generalize about the success of teachers in the rural schools of our early Republic. The teacher made memorization the students major task. The young scholars studied at their desks in preparation for rote recitation in front of the master. Repetitive drilling and a little physical discipline constituted their entire elementary education.

The teachers of the district school were examined in most academic disciplines, as well as other branches that were prescribed by the district school committee or superintending committee; these could possibly include the study of surveying, algebra, geometry, bookkeeping, philosophy, chemistry, or any of them and other suitable studies. Teachers proposing to teach in such schools were examined in those branches in addition to those required of other supervising teachers.

New Hampshire district schools were closely tied to their communities. Inexpensive and under tight controls, they satisfied communities desires for elementary education.

Next page