Praise for Delight in One Thousand Characters

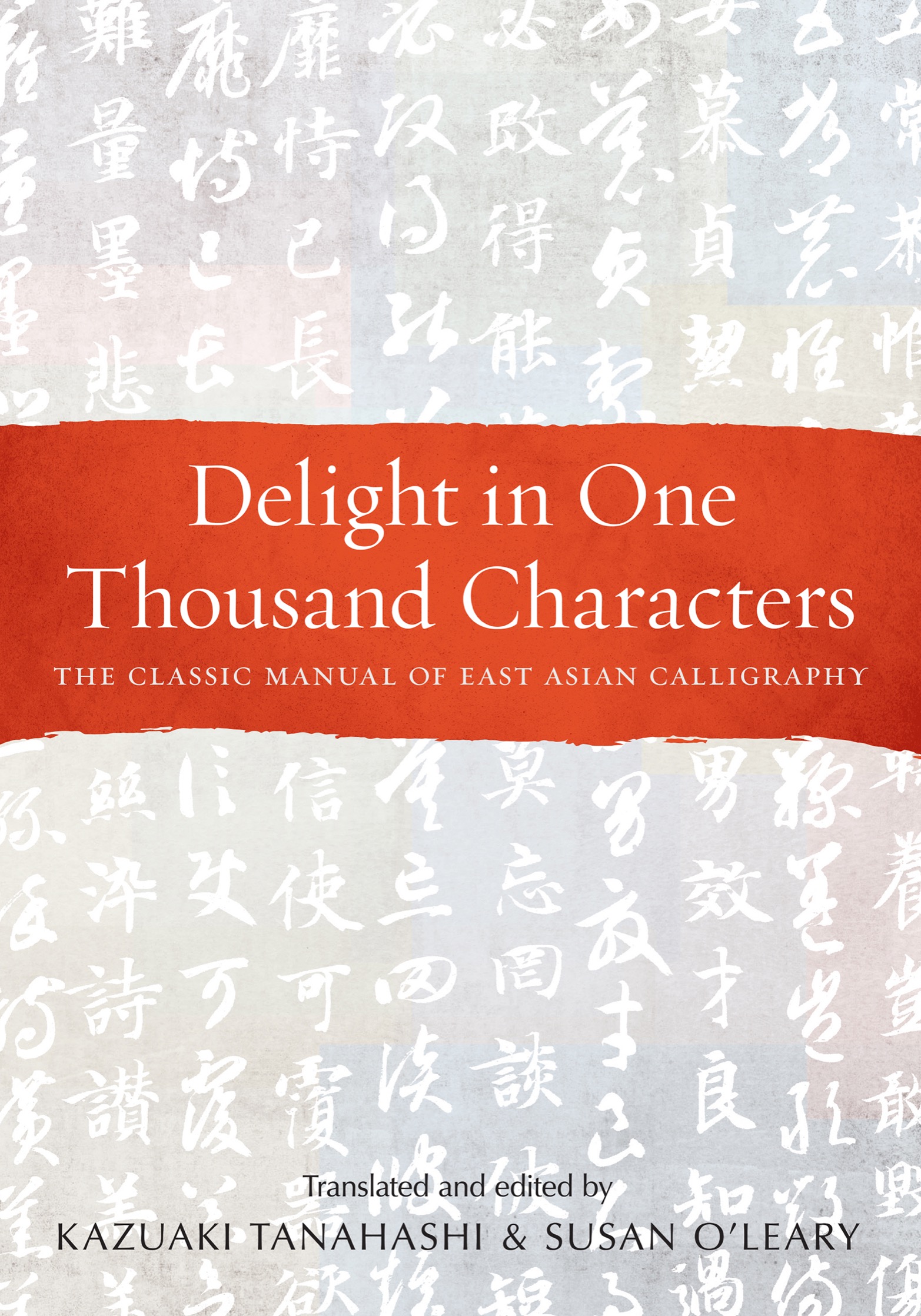

Written in the sixth century by Zhou Xingsi, the Thousand Character Essay (which is indeed exactly one thousand characters long) is both a shorthand compendium of ancient Chinese thought and the source for the standard handbook for writing Chinese characters. Kazuaki Tanahashis careful translation of this text (in collaboration with Susan OLeary) and his presentation of the classic sixth-century calligraphing of it by monk Zhiyong springs from his own lifelong practice of the art of the brush. For many decades hes produced stunning works of calligraphic art and offered workshops around the world, becoming in the process the leading exponent in the West of what might be called the philosophy of the brush. This volume reproduces the only extant complete copy of Zhiyongs brushwork, with details about forms and pronunciation in several languages. I am amazed by this book and will use it from now on as my source for writing and appreciating characters, Chinas great and enduring gift to the human family.

Norman Fischer, author of Selected Poems 19802013 and When You Greet Me I Bow: Notes and Reflections from a Life in Zen

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

2129 13th Street

Boulder, Colorado 80302

www.shambhala.com

2022 by Kazuaki Tanahashi and Susan OLeary

Cover calligraphy: Lines from the Ogawa Manuscript

Cover brushstroke: Kazuaki Tanahashi

Cover design: Kate E. White

Interior design: Steve Dyer

The Ogawa Manuscript is used with the permission of Masato Ogawa.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Shambhala Publications makes every effort to print on acid-free, recycled paper.

Shambhala Publications is distributed worldwide by Penguin Random House, Inc., and its subsidiaries.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tanahashi, Kazuaki, 1933 translator, editor. | OLeary, Susan, 1950 translator, editor. | Zhou, Xingsi, 521. Qian zi wen. English. | Zhiyong. Zhen cao Qian zi wen

Title: Delight in one thousand characters: the classic manual of East Asian calligraphy / translated and edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi and Susan OLeary.

Other titles: Delight in one thousand characters.

Description: Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala Publications, Inc., [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and indexes.

Identifiers: lccn 2020023378 | isbn 9781611808735 (trade paperback)

eISBN 9780834844384

Subjects: lcsh : Zhou, Xingsi, 521. Qian zi wen. | Zhiyong. Zhen cao Qian zi wen. | Chinese languageReaders.

Classification: lcc pl 1115 . d 45 2021 | ddc 495.1/86421dc23

lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020023378

a_prh_6.0_140788416_c0_r0

For Jim Roseberry

Love and high esteem

Contents

Chronologies of Ancient China

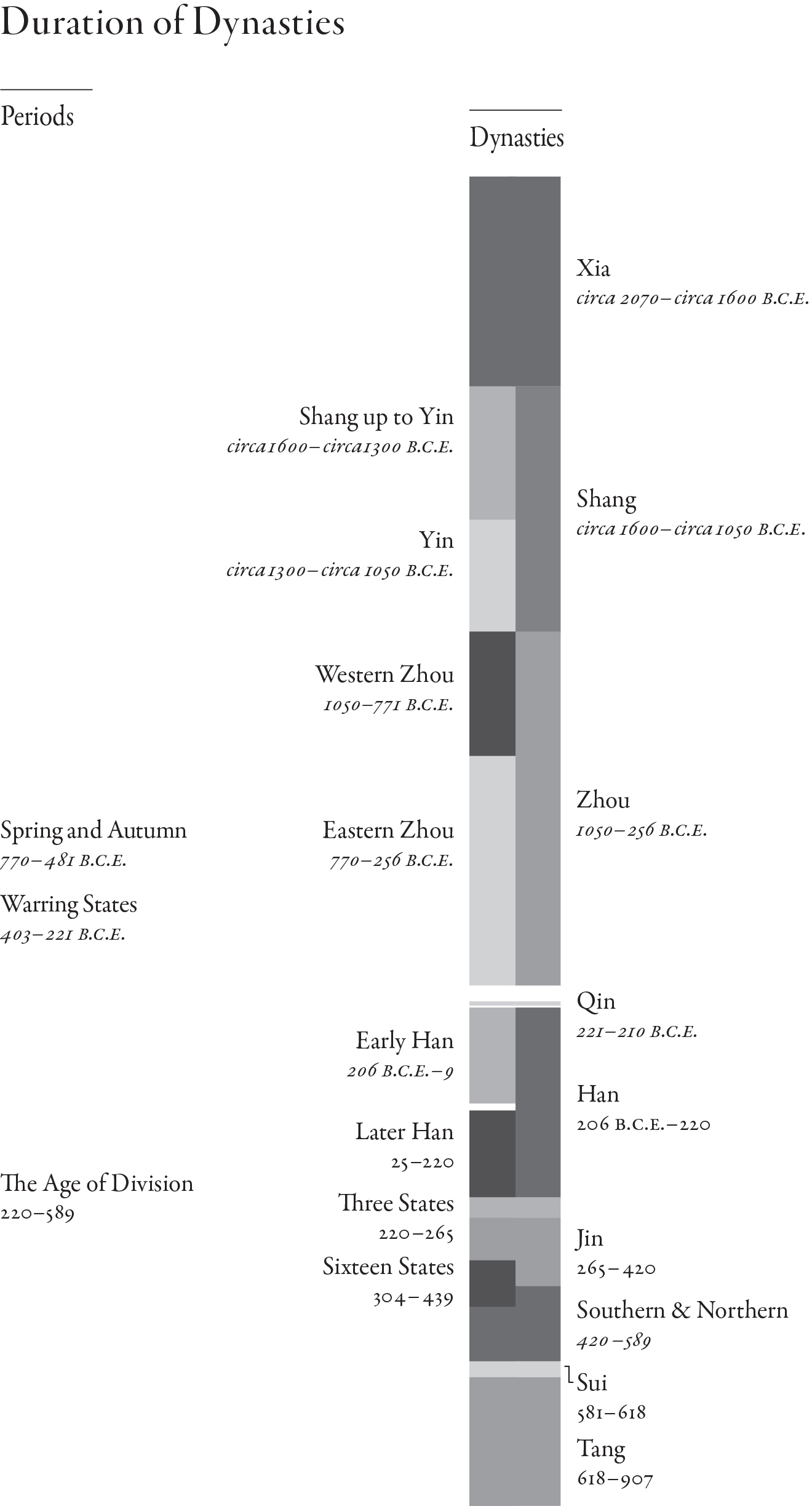

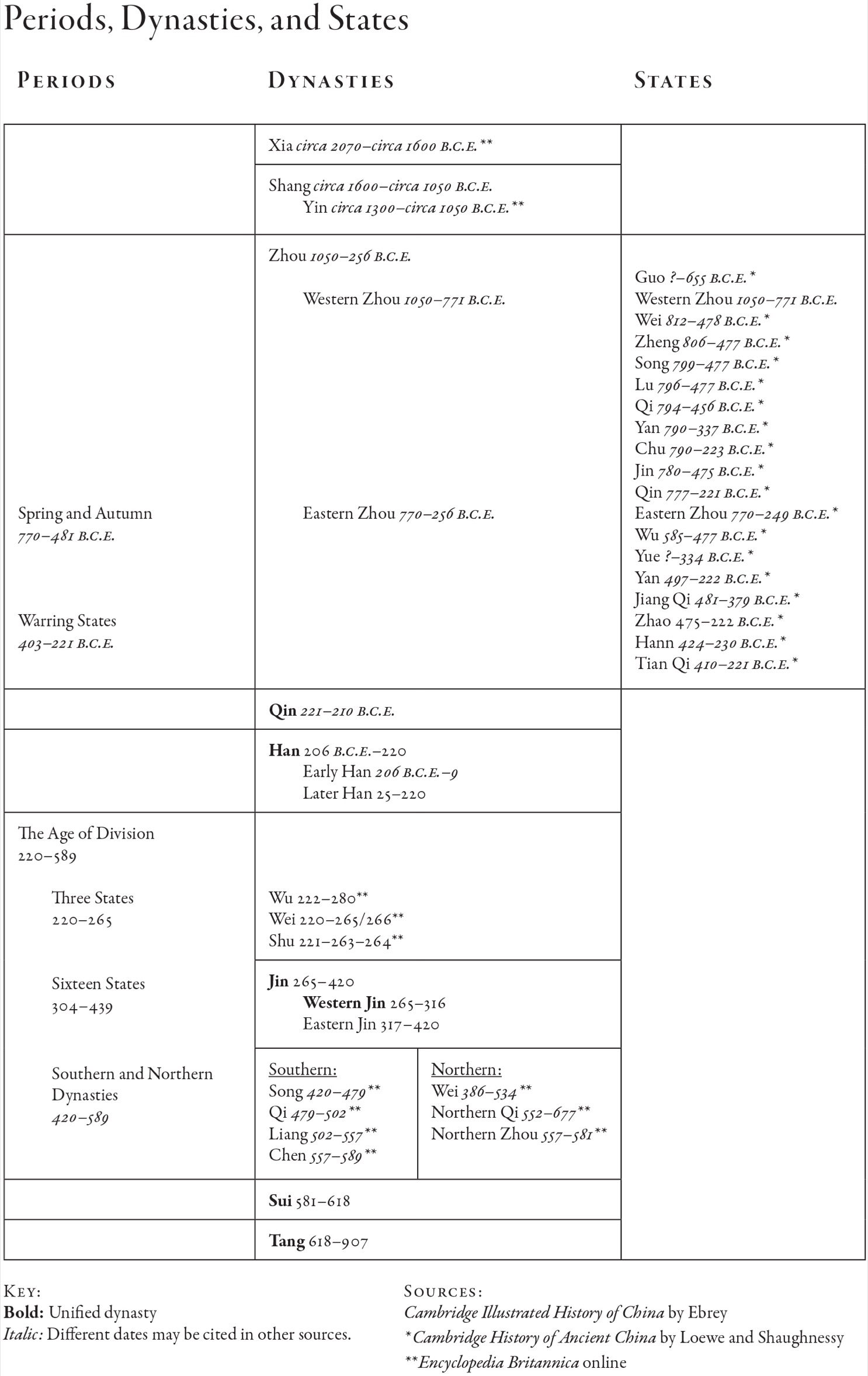

The purpose of these chronologies (located on ) is to help the reader situate the references in both Zhou Xingsis One Thousand Character Essay and our explications in the larger history of ancient China. As his and our references range from the Xia Dynasty to the Tang Dynasty, visual representations of these more than three thousand years could be helpful. The bar graph, Duration of Dynasties, shows the periods and dynasties in relation to one another and the relative amount of time dynasties lasted. Periods, Dynasties, and States, in including states of the Zhou Dynasty, goes to the level of detail in Zhou Xingsis text.

A common framework for studying ancient Chinese history is dynasties and periods. These categories sometimes are complimentary and sometimes overlap. A dynasty is a succession of rulers within the same family or lineage. A period has a broader meaning and is organized more around such aspects as political and cultural commonalities within a particular time frame. When there was dynastic stability, the time frames are referred to by the ruling dynasty and the categories of period and dynasty are collapsed into one.

The Xia Dynasty is a quasi-legendary first dynasty for which no documentary or archaeological evidence has been found. The first recorded dynasty is the Shang Dynasty, its latter part being referred to as the Yin Dynasty. As Zhou Xingsi used Yin instead of Shang, we include Yin in the chronology.

The Zhou Dynasty was divided by feudal states or regional powers, Western Zhou and later Eastern Zhou in central China more prominent among them. These states were sometimes at war with one another and rose to prominence or were subsumed by inner or outer powers. Thus, for instance, the Yue state came to an end when conquered by Chu in 334 b.c.e . This ongoing change is why the dates given for the Zhou states do not correlate exactly with the dates for the dynasty and periods. Similarly, the dates for Northern Qi do not correspond exactly with the dates for Southern and Northern Dynasties.

There were also periods of instability between some dynasties, as, for instance, from the end of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty in 256 b.c.e . to the unification of China by Qin in 221 b.c.e . These are shown by empty white space in the bar graph.

Finally, different scholars give different dates for ancient Chinese periods and dynasties. When there is accord as to dates, we give them in regular script. When there is not accord, dates are given in italics.

Preface

Susan OLeary

Soil is not yellow. it is ochre .

On an autumn visit to my home, Kaz was sitting at my kitchen table, keeping me company as I cooked dinner, and was talking about the fourth ideograph of the One Thousand Character Essay, . It had been translated as yellow in the English texts Kaz was using that week to teach a calligraphy workshop on the work of the sixth-century Chinese monk Zhiyong.

In parts of China, the earth is an orangish-yellow, but it is not yellow.

This was the first intimation I had that Kaz was thinking of writing a book on Zhiyongs calligraphy.

It was Kaz the translator, precise about each word and each meaning. Kaz the calligrapher, enjoying the grace of Zhiyongs elegant brushing and the resonance between Zhiyongs formal and cursive scripts. Kaz the scholar, with his knowledge of the vocabulary, history, philosophy, and beliefs of China in early Common Era centuries. And as we moved into work on this book, it was Kaz the teacher, generous and focused in his intention to both share the history of the One Thousand Character Essay