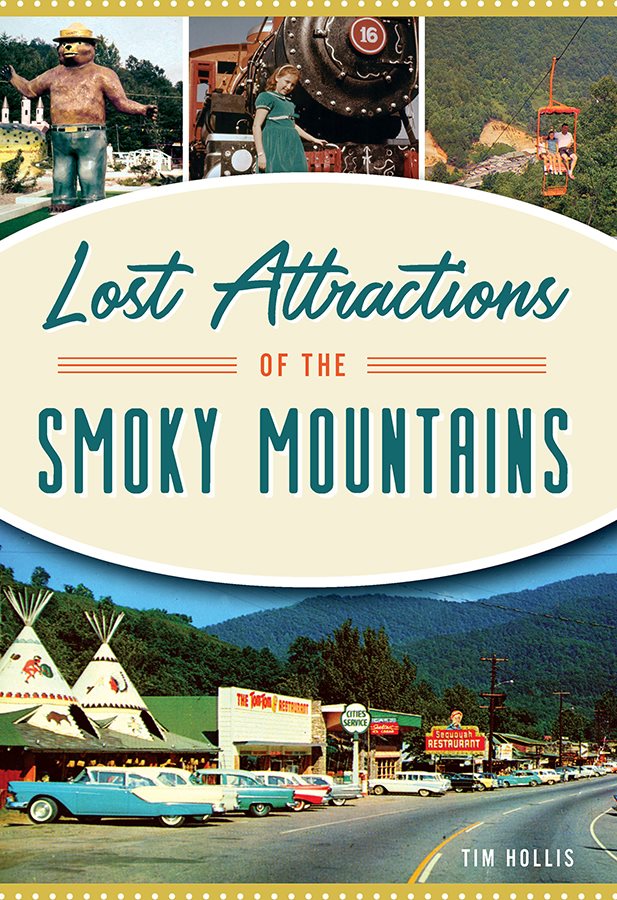

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by Tim Hollis

All rights reserved

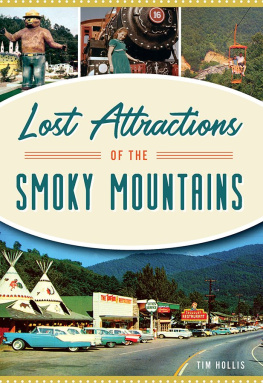

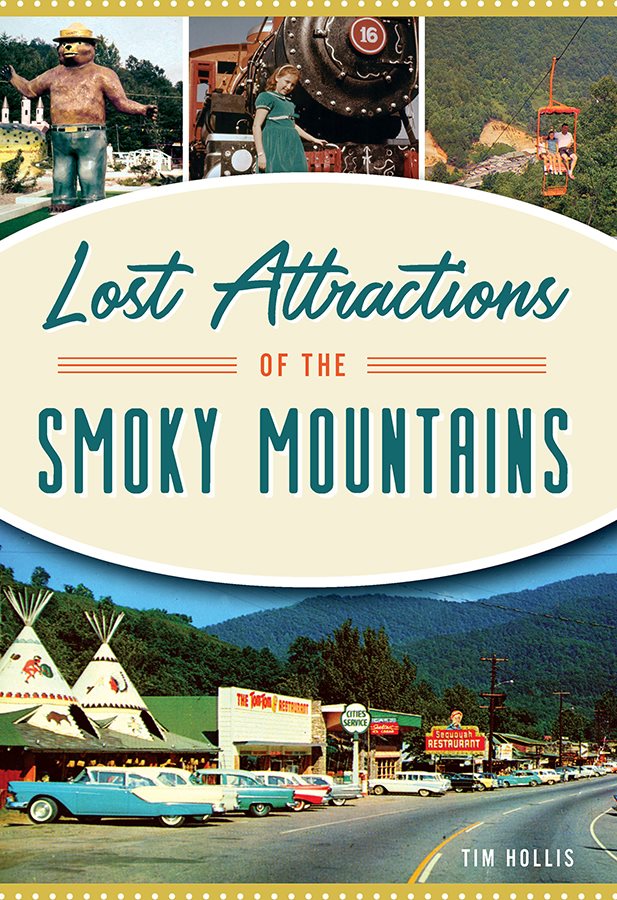

Front cover, top left: Becky Craddock collection; top center: Mitzi Soward collection; top right: authors collection; bottom: authors collection.

First published 2020

E-book edition 2020

ISBN 978.1.43966.961.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019956044

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.412.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

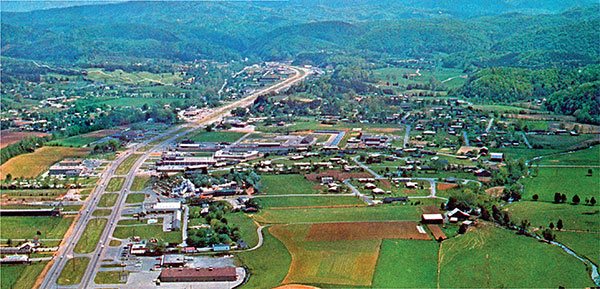

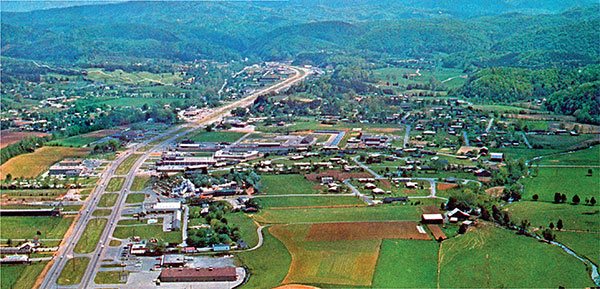

In the pages that follow, we will be seeing dozens of Great Smoky Mountains attractions that no longer exist. But the view captured in this incredible mid-1970s aerial of Pigeon Forge is also a sight that no longer exists. Note the comparatively barren roadside landscape of U.S. 441, looking south toward Gatlinburg and the mountains. Tiny motels abound, with only the concrete volcano of the Magic World theme park (lower center) hinting at the explosion of attractions yet to come. Authors collection.

Acknowledgements

Although most of the material you will see in the pages that follow originated in my own decades-long collection of memorabilia, credit must be given to the additional sources that enlivened the result. As you will notice in the credit lines for the photos, a number of them come from fellow tourism collectors and photographers: Shelia Atchley, Billy Baker, John Burgess, Becky Craddock, Bob Howard, Butch Hudson, Loren Jones, Joy Stout Jucker, Jeremy Kennedy, Brian McKnight, Mark Pedro, Warren Reed, Katie Sidwell, Mitzi Soward, Skylar Spake, Jerry Thompson and Cyndy Woller. We must also acknowledge the late photographer John Margolies, who bequeathed his personal archive to the Library of Congress with the amazing stipulation that no restrictions were to be imposed on its use by other authors and researchers.

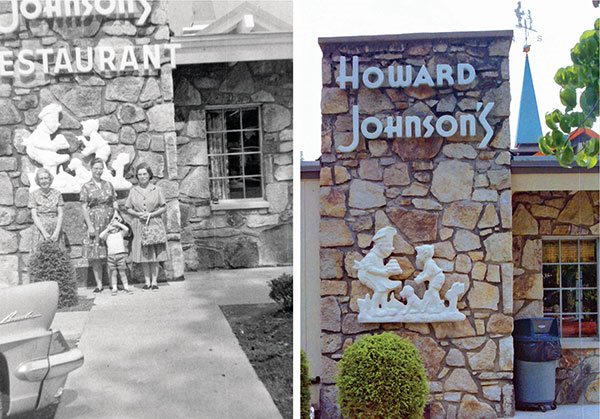

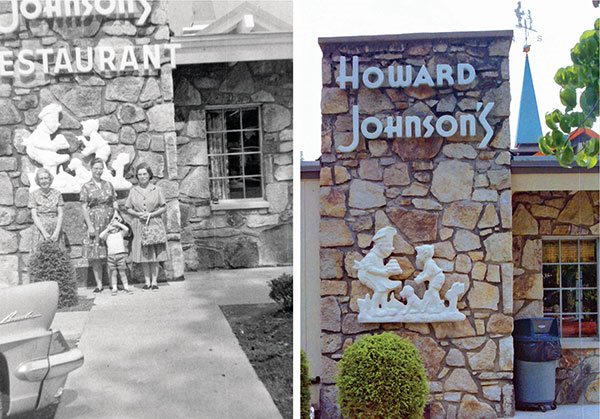

The authors first visit to the Smokies was at age three in August 1966. In the left-hand photo, you can see him and his family when the world was still in glorious black and white, having lunch at Gatlinburgs Howard Johnsons restaurant. The right-hand photo was taken in 1985, at which time Simple Simon and the Pieman were still hanging at HoJos as if nineteen years had not passed. Both, authors collection.

Introduction

Welcome, friends, to the latest volume in the ongoing Lost Attractions series. For those who are new in this neighborhood, perhaps it would be best to begin by explaining the title. Just what is a lost attraction of the Great Smoky Mountains, anyway? Well, it is very simple. A lost attraction can be any type of tourism-related businessroadside attraction, motel, restaurant or otherthat no longer exists. Casually flipping through the pages, one may conceivably run across an image and comment, Hey, that place is still there! That would bring us to the secondary definition: a business that has changed radically over the years and no longer resembles its depiction in vintage photos and postcards, even though technically it may still be operating. Everything clear now?

My own personal connection to the Smokies goes back to when I was three years old. Apparently, by that time my parents had decided that I was old enough to withstand the environment of a road trip, and for reasons that are now unknown to me, they chose the Smokies as our initial destination. Judging from the photos my dad shot with his trusty 35mm camera on the trip, it appears that we saw Gatlinburg only by passing through it, spending most of our time on the other side of the mountains in Cherokee. Maybe the fact that my mom always loved Western movies had something to do with it, but considering how badly she hated any kind of vacation trip that meant leaving home and her beloved cats, I doubt that Cherokees appropriation of the customs and costumes of the Plains Indians had any influence on our itinerary.

Looking back through the lens of history, what is really bizarre is to realize that at the time of our visit (August 1966), Smokies tourism was only about thirty-five years old. The geographical isolation of the mountain country had ensured that hardy farmers had been scraping out a living in the valleys of the Smokies for centuries with very little contact with the larger outside world. For the well-to-do people in Knoxville, the nearest city of any size, the communities of Sevier Countyincluding Gatlinburg, Pigeon Forge and Seviervilleseemed to be quaint reminders of a bygone day. It was this thinking that prompted the Pi Beta Phi sorority to establish a school in Gatlinburg in 1912, first, to help educate the uneducated, and second, to establish an arts and crafts program to preserve the way the mountaineers had been doing things all along.

Craftsof the mountain variety on the Tennessee side and Native American on the North Carolina sidedrew some tourists into the isolated region, but it was when the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was established in bits and pieces between 1934 and 1940 that the tourism industry really got started. Improved roads, allowing access to the new national park, had a lot to do with it, and by the time World War II and its travel restrictions were over, the region was ready for success. Now, lets pile into our Chevrolet and see what the USA once had to offer in those formerly sleepy Smoky Mountain communities.

CHAPTER ONE

Hillbillies and Indians and Bears, Oh My

We will begin our tour of the Smokies lost, if not completely forgotten, attractions with the most logical ones: the places that made at least an attempt to tie themselves to the regions native culture. On the Tennessee side of the mountains, that translated into bears and hillbillies; crossing the national park via U.S. 441 brought tourists into an alternative universe where bears remained but their human counterparts were Native Americansnot always, however, the ones who had occupied that land for hundreds of years.

The attractions and other businesses that employed these stereotypes were among the first to spring up once the area had discovered that there was gold in them thar touristers. While handicrafts were the initial draw on both sides of the mountains, it did not take long for business owners to latch on to the depiction of mountaineers and American Indians as portrayed in motion pictures, animated cartoons and comic strips. Bears were yet another matter. As we shall see, they were often depicted in their natural state, but even more frequently they were caricatured into a cartoony form that would have been quite at home with Yogi and Smokey and their fellow ursine celebrities. Turn the page, and you will begin to see what we mean.

Next page