All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

P.O. Box 703

Distributed by Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

The Language of Houses

How Buildings Speak to Us

Alison Lurie

Illustrations by Karen Sung

For my sister Jennifer

Contents

Chapter 1

What Buildings Say

A building is an inanimate object, but it is not an inarticulate one. Even the simplest house always makes a statement, one expressed in brick and stone and plaster, in wood and metal and glass, rather than in wordsbut no less loud and obvious. When we see a rusting trailer surrounded by weeds and derelict cars, or a brand-new mini-mansion with a high, spike-topped wall, we instantly get a message. In both of these cases, though in different accents, it is Stay Out of Here.

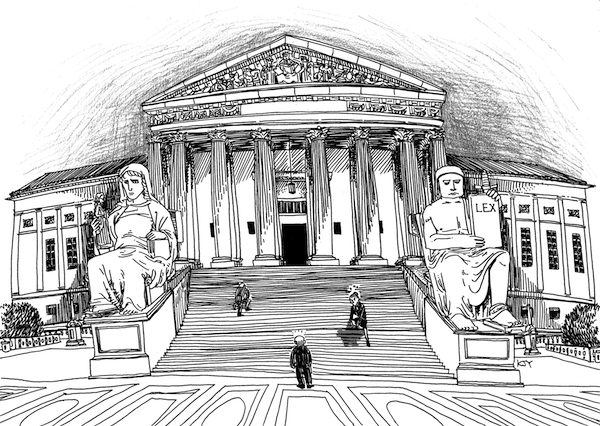

It is not only houses, of course, that communicate with us. All kinds of buildingschurches, museums, schools, hospitals, restaurants, hotels, stores, and officesspeak to us silently. Sometimes the statement is deliberate. A store or restaurant can be designed so that it welcomes mostly low-income or high-income customers; a church or temple can announce that God is a friendly neighbor, a stern judge, or a remote and inaccessible spirit. Buildings tell us what to think and how to act, though we may not register their messages consciously.

In this sense, architecture is a kind of language, one that most designers, builders, and decorators speak, sometimes fluently and sometimes clumsily, and that all of us hear. In many ways it is a more universal language than words, since it uses three-dimensional shapes, colors, and textures rather than words. We may be at a loss to understand what is said in most foreign languages, but almost every building conveys information, though we may not understand all of it. And, like spoken and written languages, architecture may be formal or casual, simple or complex.

FORMAL AND INFORMAL

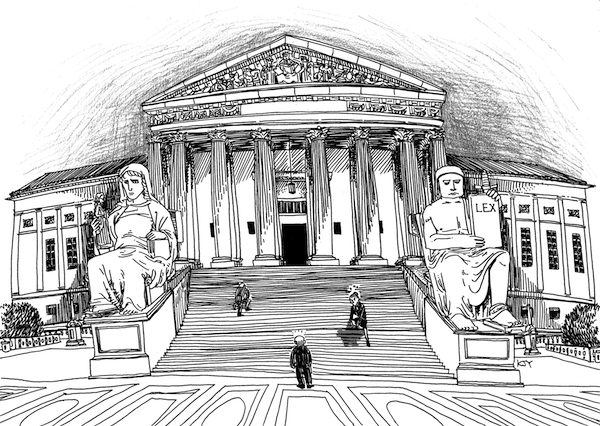

Formal speech is weighty, balanced, without hesitations, interruptions, or incomplete sentences: we hear it in a written and rehearsed political oration or public lecture. Formal public buildings, from an early Greek temple to the latest state capitol, have been carefully planned. They tend to be bilaterally symmetrical from a front or rear view: one side is a mirror image of the other. Any internal asymmetry (the placement of bathrooms and closets, for instance) is invisible from outside. Many grand private homes, including most great European and American mansions of the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, were bilaterally symmetrical. The formal regularity of their faades, both front and rear, suggested that what went on within them was equally formal and well regulated.

Buildings that look symmetrical only from in front are more common. The town hall and the library, as well as the classic Southern mansion, Cape Cod cottage, or Colonial Revival house, with their central doorways flanked by identical windows, all suggest formality, especially when there is a front walk with matching trees or flower beds on either side. Seeing such a building, we assume (not always correctly) that life inside it will be well ordered and perhaps rather conventional. Often, however, in the back of these structures there will be uneven additionsas well as sheds, garages, porches, and decksthat suggest a more complex private life.

Informal speech is colloquial, often impetuous, and fragmentary. Informal architecture also usually seems casual and unplannedas if it just grew, which is often the case. Most people who buy a house eventually make alterations if they can afford it. As a result, over the years the original structure of a building may have been altered many times. Wings may have been extended, a bay window pushed out, a porch added or removed. Most buildings dont stand still over time: they grow and shrink; different tenants move in, and as they do, meanings change. When my grown son and I went to look at my parents former summer house on the ocean in Maine, we were sad and even rather angry to see that the big screened porch where we all used to sit had been enclosed and turned into just another room. The house was larger and more impressive now, but less open and welcoming.

SIMPLE AND COMPLEX

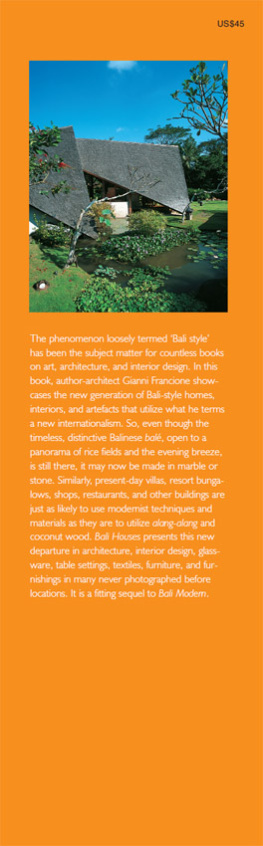

Like speech, architecture can be simple or complex. Simple speech favors short words and sentences, with few adjectives and adverbs and similes. Simple architecture, too, is largely unadorned. The basic nineteenth-century American farmhouse, shotgun cabin, or little country church recalls the simple songs and ballads of an earlier time and the traditionally laconic speech of the frontier. Their minimalism may have been unplanned, the result of a shortage of money and time, or it may have been consciously chosen, like Shaker architecture. Today, the deliberate choice of simple construction is common among people who favor a back-to-the-land or green lifestyle; occasionally, however, their apparently basic buildings have in fact been expensive to build and heat and light, though the hope is always that they will save money over time as well as reducing the strain on our natural resources. Some owners may also try to create the look of a supposedly simpler and more authentic past in their brand-new houses. They use old bricks and boards that in fact cost more than new ones, and may even have fresh paint scratched and scraped to create a distressed look.

In most of Europe and America there seems to have always been an instinctive propensity toward constructing simple rectangular buildings with sloping roofs that shed rain and snow easily. This basic pattern even appears in childrens drawings. The French architectural historian Gaston Bachelard speaks of the picture so often drawn by children, and known to psychologists as the Happy House. It is usually a square one- or two-story home with a peaked roof, a central door, and two or more symmetrically placed windows. There is often a chimney from which smoke rises, implying that the building is warm and inhabited. Frequently the Happy House is surrounded by simple lollipop-shaped trees and/or outsize flowers, and a big round yellow sun shines in the sky, which is indicated by a strip of bright blue at the top of the drawing.

Unhappy or disturbed children will sometimes produce a version of this picture in which the strip of sky is black, and there is no sun. Their houses often have no windows, or only black squares, implying that nobody can see in or out; bad things presumably go on in such a building. In extreme cases, the Happy House may collapse entirely. The New York Times, in an article about the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, reported that many children who had lived through the storm drew not an entire house but simply a triangle representing its roof and attic, possibly the only part that remained above water: windows and stick figures sometimes appeared inside this triangle.