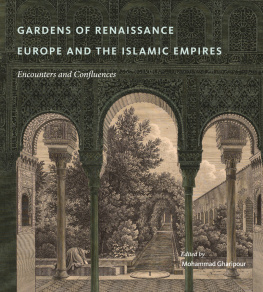

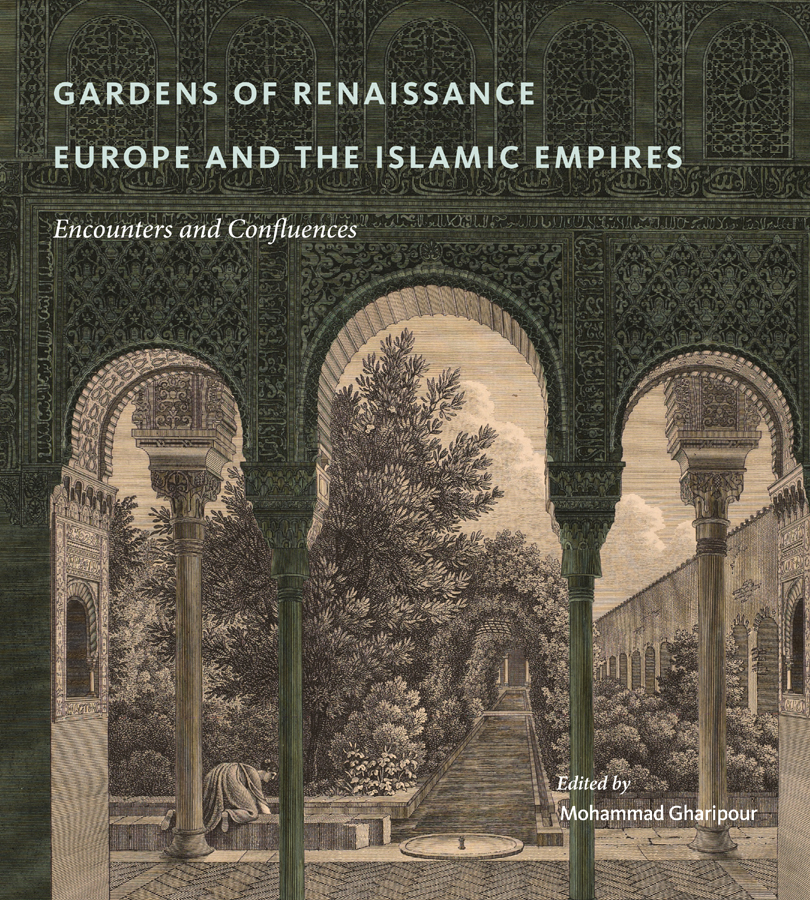

GARDENS OF RENAISSANCE EUROPE AND THE ISLAMIC EMPIRES

GARDENS OF RENAISSANCE EUROPE AND THE ISLAMIC EMPIRES

Encounters and Confluences

Edited by

Mohammad Gharipour

The Pennsylvania State University Press

University Park, Pennsylvania

The publication of this book was supported by the David R. Coffin Publication Grant of the Foundation for Landscape Studies.

The publication of this book was supported by a grant from the Barakat Trust.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gharipour, Mohammad, editor.

Title: Gardens of Renaissance Europe and the Islamic empires : encounters and confluences / Mohammad Gharipour, editor.

Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: A collection of essays exploring similarities between gardens and designed landscapes in Europe and the Islamic world after the fifteenth century. Essays identify possible direct or indirect influences and examine transcontinental mutual influences in garden designProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017005890 | ISBN 9780271077796 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: GardensEuropeHistory. | GardensEuropeDesignHistory. | GardensIslamic countriesHistory. | GardensIslamic countriesDesignHistory. | Gardens, EuropeanHistory. | Islamic gardensHistory. | Gardens, Renaissance.

Classification: LCC SB466.E9 G376 2017 | DDC 635.094dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017005890

Copyright 2017 The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Printed in Korea

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 168021003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI Z39.481992.

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The period described as the Renaissance was a significant turning point in European history, an era of cultural and economic changes that shaped the identity of the West. This new identity was based in part on a revolutionary shift in knowledge about the world beyond Europe, when, during the process of constructing the other, and the subsequent evolving constructions of non-Western cultures, some civilizations were subcategorized under the homogenizing term Islamic. Engagement with these non-Western lands, generated by published accounts of European travel, opened new doors for cultural and economic exchanges. Strong political, commercial, and cultural relations between Europeans and three Islamic empiresthe Ottomans in Turkey, the Safavids in Persia, and the Mughals in Indiavastly enhanced European knowledge of Islamic gardens and architecture. Many travel narratives from this period describe cities, gardens, and buildings, often characterizing them as sites of social interaction. Drawings and sketches of Islamic cities and gardens in some of the accounts accelerated European interest in Islamic architecture. Intellectual and artistic exchanges beyond those undertaken by travelers, merchants, ambassadors, and missionaries also added to the reciprocal flow of ideas and concepts in terms of architectural and garden design.

The Renaissance was also an era of discovery for Europeans. As well as scientific discoveries and artistic innovations, an international network of trade, formed and established during the late Middle Ages, was utilized by European travelers. Their voyages had various purposes. While the Portuguese sought to establish new trade routes to India, the Moluccas, and Japan, the Venetians tried to maintain their control over the existing commercial channels.

World history, however, was written primarily by Western intellectuals, with an inbuilt tendency to marginalize Eastern history. The same trend is visible in the field of garden history, drafted by American and European historians in the last two centuries. In comparison to studies of European gardens, the field of Islamic gardens is relatively young and still underdeveloped, partly due to the dearth of research on literary and visual documents and the underresearch of archeological sites and objects. All of this necessitates a new perspective on gardens, offering a more balanced approach that appreciates the diversity of traditions without prioritizing a specific garden typology.

Such an approach requires an understanding of the concept of In either instance, cultural diffusion is a two-way street, and the culture of the dominant society is equally affected. This, in the long run, can lead the society to a multicultural environment where different cultures coexist and establish mutual interactions.

But how is this related to a discussion on garden design in Europe and the Muslim world? The study of Renaissance Europe indicates extensive connections with the Middle East and North Africa. Direct connections in trade and politics played a significant role in the development of gardens in both regions. However, while the Ottomans maintained a direct relationship with Europeans, especially the French, exchanging gardening concepts and plants, there are no documents confirming the official exchange of ideas between the Safavid and British courts. In other words, direct political relations did not necessarily result in influences or borrowings in garden design and horticulture. Nonetheless, it cannot be denied that printed travel accounts and sketches of gardens and urban landscapes must have familiarized European intellectuals with Eastern garden design. During this period, some simultaneous changes occurred in garden design in both Europe and Persia. The role of gardens within cities also grew in prominence, with a gradual shift in gardens from the private sphere toward an increasingly public function. As a natural consequence of this shift, gardens began to serve as the core of new urban plans and designs. This development not only established a new relationship between the garden and the city, but also emphasized the garden pavilion or villa as the focal point of city planning. Are such concurrent developments in European and Islamic gardens the result of concurrent political and social changes in both regions, or could these garden design traditions have mutually influenced one another?

About This Book

Although indebted to previous studies that focused on specific regions, this book aims to highlight transcontinental cultural, economical, and political relations in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Its main goal is to pinpoint similarities between gardens and designed landscapes in European and Islamic traditions, while identifying possible direct or indirect influences, and to examine transcontinental mutual influences in garden design after the fifteenth century between Europe and the Islamic world. Illustrating commonalities in design, development, and perceptions of gardens and nature more generally, this books chapters substantiate important parallels between the revolutionary developments in garden design in both regions, relating them to political, economic, and cultural changes within European and Middle Eastern societies.

CONTENTS

CONTENTS