The proboscis monkey has evolved a large nose that amplifies its calls to warn other monkeys of danger. These monkeys also swim to avoid predators.

When I was young, my parents enrolled me in a book club about nature. Each month a volume about an ecosystem or grouping of related animal species appeared in our mailbox. Most pages in each of the paperback volumes featured an empty box that readers were invited to fill with a photo of the correct animal. The volumes provided the photos in a grouping of separate pages of full-color photographs. It was my job to place each of the photographs in the correct empty box in the books pages.

I acquired book after book Life in the Everglades, Wildlife of Australia, Birds of Prey. I felt as if I were traveling the world, adding creature after creature to my list, as if I had encountered them on safaris and expeditions.

I spent much of my childhood with this zeal for the natural world. Yet it might have been my ninth-grade honors biology class that ignited my passion to be a naturalist. There, I peered through microscopes at my own eyelashes and then, adjusting the lens, at insect scales and skin cells. I handled tarantulas and hummingbirds encased in Plexiglas cubes and glass tubes. I listened to tapes of howler monkeys and whale songs. I puzzled my way through the taxonomic naming system that organizes the whole of the plant and animal kingdoms, memorizing each species, genus, family, order, class, and phylum. But most profoundly, these experiences created an unquenchable curiosity. They convinced me how tiny our human presence is when compared to the planets nearly immeasurable diversity.

Michael J. Rosen and his Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog live and explore in the Ohio foothills of the Appalachians.

Extreme Elegance

As an adult, I live on a 100-acre (40.5 ha) farm in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. I continually see how every creature, in its own competitive niche, has evolved ways to compete for territory and mates, and to eat and not be eaten.

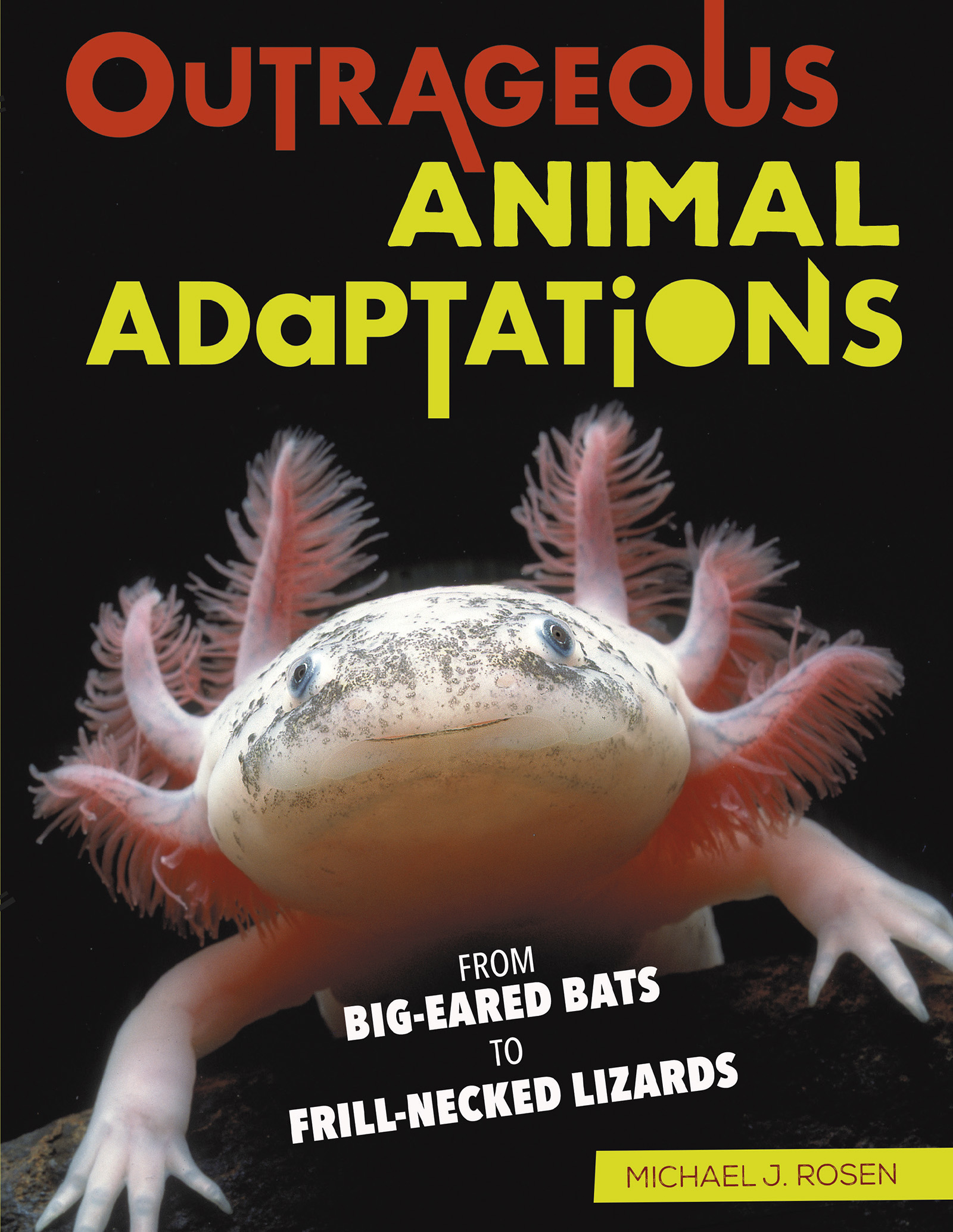

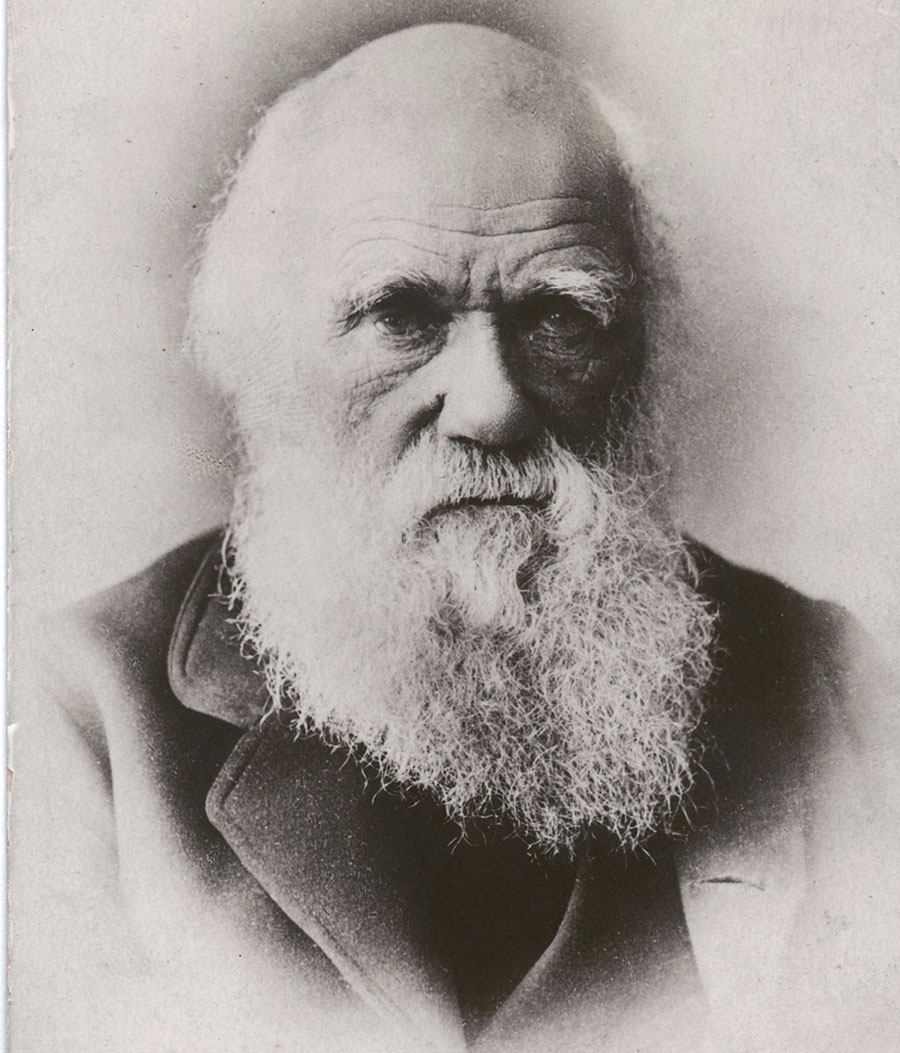

This book showcases animals whose survival strategies are among the planets most extreme. Every creature in the book proves how elegantly, over thousands of generations, a species can transformin size, shape, color, behavior, or sensory abilitiesto meet the challenges necessary to survive and ensure the future of its kind. In fields such as biology, chemistry, and math, the word elegant hardly means chic or smartly dressed. Rather, elegance refers to simplicity, concision, and a concepts ability to truly solve the problem it addresses. For example, when the nineteenth-century English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley read about Charles Darwins theory of evolution and natural selection, he reportedly commented, How extremely stupid not to have thought of that!

Charles Darwin publicly introduced his theory of evolution in 1858. The theory states that all of life is related. Complex creatures evolve from simple organisms over time through genetic mutation. The mutations that help organisms survive are preserved and passed to the next generation.

The axolotls mane of frilly gills and the naked mole rats squinty, buck-toothed face and the proboscis monkeys reddish honker may seem bizarre or outrageous. But each represents something simultaneously simple and yet decisive. Each feature or adaptation solves a particular predicament in a purposeful manner.

So even if you gasp or cringeor even furrow your brow in disgustas you read about the two dozen oddities featured here, I hope youll also marvel at their eleganceat the exquisite adaptations each remarkable survivor has evolved.

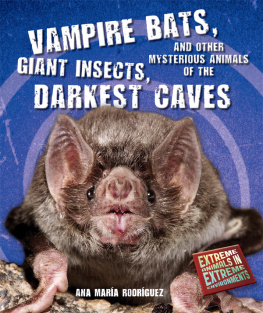

Townsends Big-Eared Bat

Life (Almost) without Gravity

(Corynorhinus townsendii)

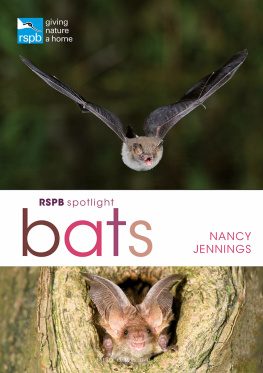

This big-eared bat flies with its ears extended forward. The large ears help funnel sound into the ear canal.

Adaptations

This bat uses its huge ears for echolocation. The bat makes a series of high-pitched sounds and listens for the sounds to bounce back from the environment. This allows the bat to figure out where things are. The ears also help the bat lift off into flight and regulate its body temperature.

Sure, you say, bats have some amazing traits. For example, the tube-lipped nectar bats tongue is one and a half times longer than its entire body. Its so long it retracts all the way into its rib cageand may take the prize for the battiest body part. But the length of the ears of the Townsends big-eared bat, at 1.5 inches (3.8 cm), is one-third of this little critters body length. And far from clumsy, these pinnae, or outer ears, are surprisingly useful.

During an evening hunt, this insectivore (insect eater) is all ears. The pinnae can extend completely forward or lay back along the bats body. Using echolocation, the bat tracks its prey. When sound waves bounce off a moth or other tasty morsel, the bats satellite-dish ears pick up the sounds again. Then the bats brain can pinpoint the preys size and course of flight by comparing the information that each ear gathers. For instance, a louder echo bounce back means a larger insect is reflecting the sound. If the left ear reports the echo first, that means make a left for the next bite!

When the bats arent hunting, theyre hanging. Hanging upside down offers a bat an advantage. Roosting in high places, theyre out of reach from many predators. Theres plenty of unoccupied real estate for hanging under a bridge or on the craggy ceiling of a cave too. To help the bats inverted lifestyle, each foot has evolved a locking tendon to keep the bats toes in a gripping position. When the bat is hanging upside down, its own weight causes its toes to close around whatever the bats holding onto. The tendon locks into place so the bat can relax rather than continually contracting its muscles to hold tight.