| skirt! is an attitude spirited, independent, outspoken, serious, playful and irreverent, sometimes controversial, always passionate. |

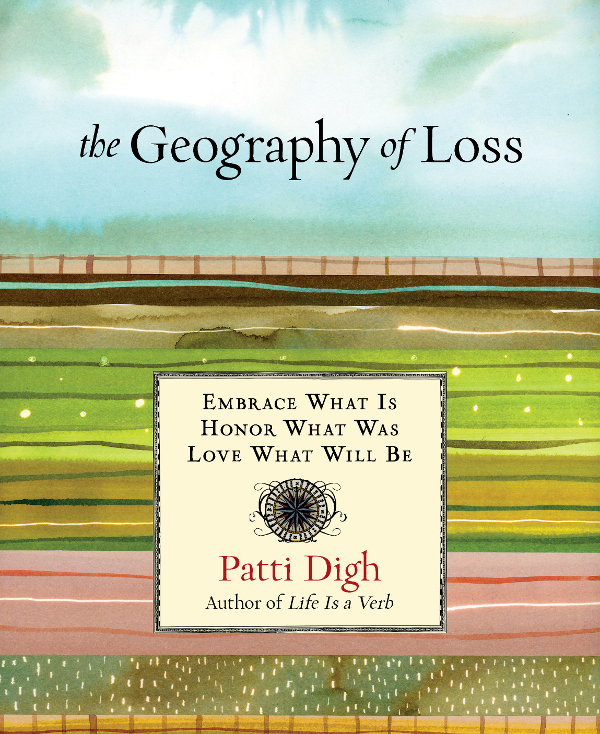

Copyright 2014 by Patti Digh

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

skirt! is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press

skirt! is a registered trademark of Morris Publishing Group, LLC, and is used with express permission.

Text design: Sheryl Kober

Layout: Maggie Peterson

Project editor: Ellen Urban

Ellen Bass, The Thing Is from Mules of Love. Copyright 2002 by Ellen Bass. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, Inc., on behalf of BOA Editions Ltd., www.boaeditions.org

Jane Kenyon, Otherwise from Collected Poems. Copyright 2005 by The Estate of Jane Kenyon. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, Inc., on behalf of Graywolf Press, www.graywolfpress.org

Pride from Hovering at a Low Altitude: The Collected Poetry of Dahlia Ravikovich by Dahlia Ravikovitch, translated by Chana Bloch and Chana Kronfeld. Copyright 2009 by Chana Block, Chana Kronfeld, and Ido Kalir. English translation copyright 2009 by Chana Bloch and Chana Kronfeld. Used by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Digh, Patti.

The geography of loss : embrace what is, honor what was, love what will be / by Patti Digh.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-4930-0414-0 (epub)

1. Loss (Psychology) 2. Grief. 3. Self-help techniques. I. Title.

BF575.G7D545 2013

155.93dc23

2013030991

For all of us who have been broken open.

The Thing Is

To love life, to love it even

when you have no stomach for it

and everything youve held dear

crumbles like burnt paper in your hands,

your throat filled with the silt of it.

When grief sits with you, its tropical heat

thickening the air, heavy as water

more fit for gills than lungs;

when grief weights you like your own flesh

only more of it, an obesity of grief,

you think, How can a body withstand this?

Then you hold life like a face

between your palms, a plain face,

no charming smile, no violet eyes,

and you say, yes, I will take you

I will love you, again.

Ellen Bass

Once there were brook trout in the streams in the mountains. You could see them standing in the amber current where the white edges of their fins wimpled softly in the flow. They smelled of moss in your hand. Polished and muscular and torsional. On their backs were vermiculate patterns that were maps of the world in its becoming. Maps and mazes. Of a thing which could not be put back. Not be made right again. In the deep glens where they lived all things were older than man and they hummed of mystery.

CORMAC MCCARTHY, The Road

Not until we are lost do we begin to understand ourselves.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

I hear the sound of paper tearing, ripping.

It is the sound of an old map being torn, an opening created for me to walk through.

I am suddenly thrust into a new landscape, a new map.

I feel I am drowning, though the new landscape is barren, hot, arid, scorching.

I am lost here. And alone, or so I believe.

We have all felt this. Someone we love has betrayed us, a kind of death. Or weve betrayed someone. Or our child has been arrested. Or weve lost our job. Or a friend has slept with our husband. Or weve slept with our husbands friend. Or we have experienced a heart attack and suddenly feel horribly mortal. Or a lover has died. Death itself, gone, gone.

Our eyes feel swollen in the new air. We have no familiar landmarks to guide from. They have disappearedall of them, gone. People have become strange to us. We hate them as they stand in the comfortable landscape weve just left.

And as we stand in this new desert, it is hard to imagine that others in our livesand in the worldare still standing on the edge of a brilliant, beautiful river, lush and full of what now look like superficialities to us. They go onhow is this possible? They keep arguing about petty things, they keep making appointments as if the planet hasnt tilted on its axis, they keep eating dinner like nothing happened. The anniversariesa week, a month, a year, a decadepass by without their noticing. How is this possible?

I remember first being in this barren desert when both my beloved grandfathers died within a week of each other; I was nine years old. And there again ten years later when my father lay in an intensive care unit after a seventh heart attack and suffocated in his own blood, his heart muscle a pile of mush unable to pump it out. As hard as it was to imagine that he was goneand how unfair to him that he was only fifty-threeit was more unfathomable that the world kept right on turning the next morning while my eyes were scorched to the point I had to go to the ophthalmologist for an emergency appointment before the funeral to get artificial tears, mine were so gone.

Men go abroad to wonder at the heights of mountains, at the huge waves of the sea, at the long courses of the rivers, at the vast compass of the ocean, at the circular motions of the stars, and they pass by themselves without wondering.

SAINT AUGUSTINE

So I was standing thereor, more accurately, crawling thereat the edge of this new barren land. Nothing to hold on to, no familiar landmarks by which to gauge my location, just knowing he was gone, gone, and unable to reconcile that reality with the fact that I knew deep inside me, even at that age, that he wasnt gone and never would be, in a much deeper sense. But what I wanted then was him, the him I knew and could see and who cooked me pancakes and made me laugh. And that him was irretrievably gone.

I remember the sound of my mother throwing up in the intensive care waiting room bathroom as the news became clear to us. I will never forget that sound, that very human, visceral reaction to loss in an alien environment, one too public and too antiseptic and too divorced from real life. The real loss would show itself at home, in the chair at the dinner table that would be forever empty. Her vomiting in that waiting room bathroom was to me then, and now, a full expression of the ways in which our body rejects loss, pushing it out of us like an alien food, something spoiled, curdling inside us.

Next page