Contents

List of Figures

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The Three Deaths of Cerro de San Pedro

The Three Deaths of Cerro de San Pedro

Four Centuries of Extractivism in a Small Mexican Mining Town

DAVIKEN STUDNICKI-GIZBERT

The University of North Carolina PressChapel Hilll

This book was published with the assistance of the Wells Fargo Fund for Excellence of the University of North Carolina Press.

2022 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Charis by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Studnicki-Gizbert, Daviken, author.

Title: The three deaths of Cerro de San Pedro : four centuries of extractivism in a small Mexican mining town / Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022031520 | ISBN 9781469671093 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469671109 (pbk. ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469671116 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Precious metal industriesMexicoCerro de San Pedro (San Luis Potos)History. | Gold mines and miningMexicoCerro de San Pedro (San Luis Potos)History. | Silver mines and miningMexicoCerro de San Pedro (San Luis Potos)History. | Mineral industriesSocial aspectsMexicoCerro de San Pedro (San Luis Potos)History. | Mineral industriesEnvironmental aspectsMexicoCerro de San Pedro (San Luis Potos)History. | Cerro de San Pedro (San Luis Potos, Mexico)History.

Classification: LCC HD9535.M63 C478 2022 | DDC 332.64/42097244dc23/eng/20220805

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022031520

Cover illustration: A. Stoicheff, Blasting at Cerro de San Pedro, February 2008. Courtesy of A. Stoicheff.

Para todos aquellos que han luchado

Por la vida en Cerro de San Pedro

y

al Coyote que me llev all.

Contents

Illustrations

Figures

Historic bullion production in Mexico, 15212020,

The geology and mining of Cerro de San Pedro,

The coat of arms of San Luis Potos,

The colonial mining metabolism,

The open-pit heap-leach mine at Cerro de San Pedro,

Cycles of extractivism at Cerro de San Pedro,

Maps

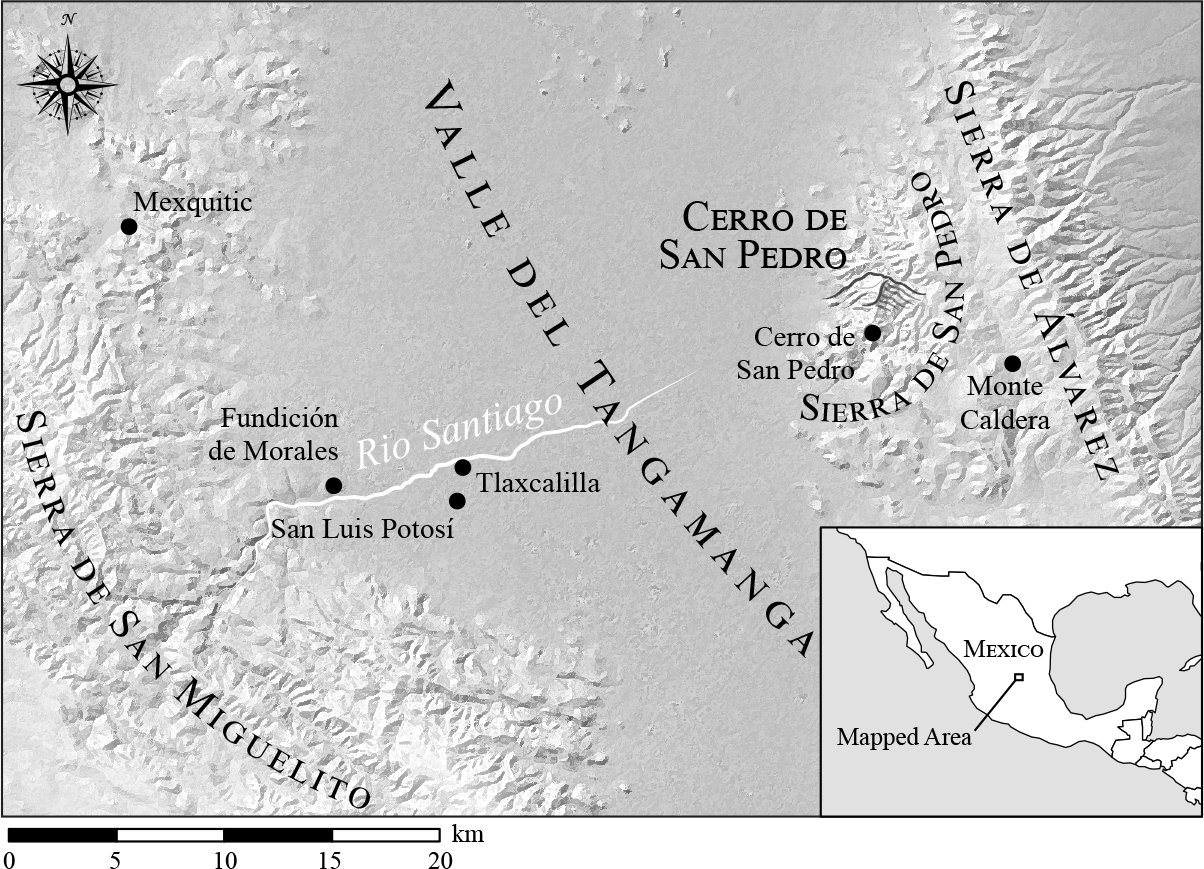

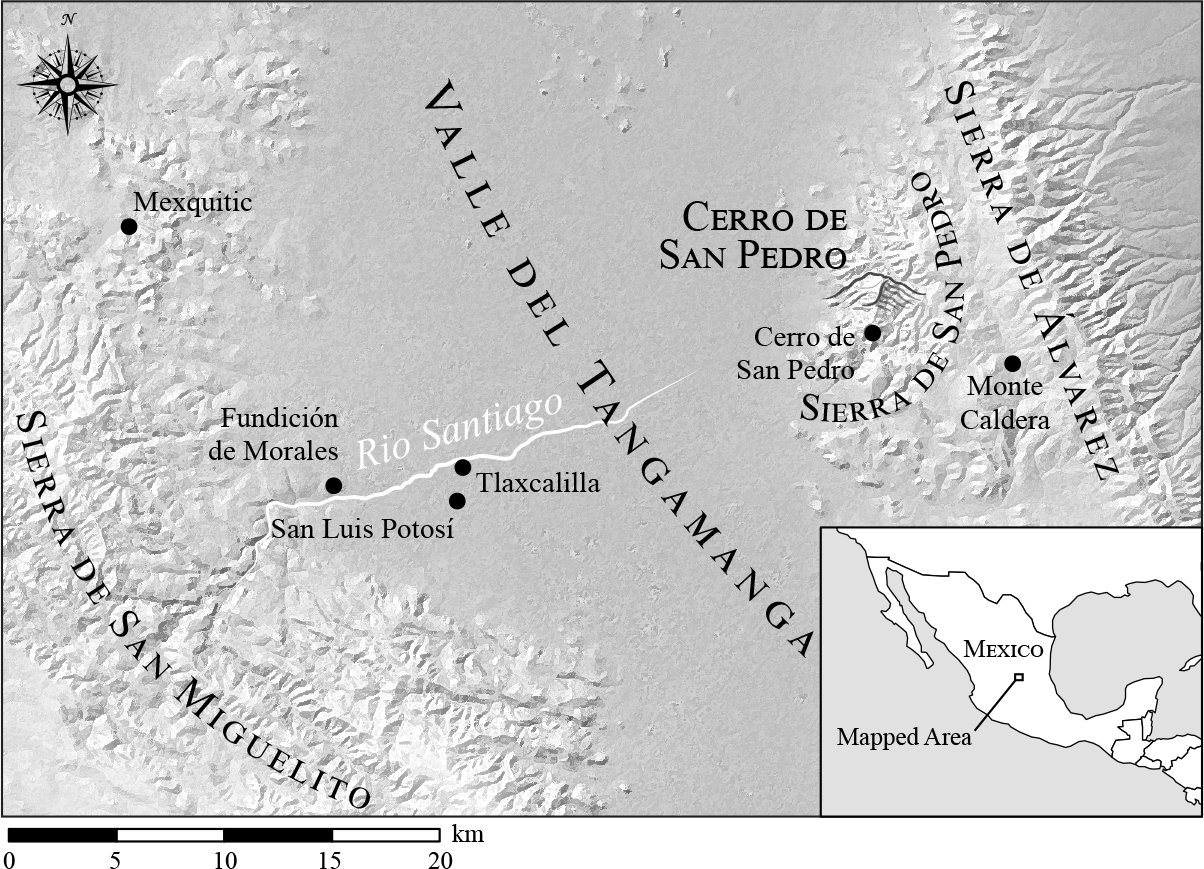

Cerro de San Pedro, S.L.P. and environs, x

New Spains northern mining frontier,

Ore processing at the Hacienda de Morales,

Industrial mining contamination study sites in Mexico,

MAP 1Cerro de San Pedro, S.L.P. and environs ( G. Wallace Cartography & GIS. Map by Geoffrey Wallace, 2021).

Preface

The following book was seeded in a conversation with my close friend and colleague Juan Carlos Ruiz Guadalajara in early December 2001. We were sitting on the steps in front of the Church of San Nicols, enjoying the view across its plaza and the small village of Cerro de San Pedro. It was my first visit. The day had been spent wandering around, taking in the quiet scenes of life within the semi-ruins of this old Mexican mining town, absorbing its atmosphere. Evening was coming on. The winds were picking up and rustling the mesquites that seemed to be everywhere colonizing the villages abandoned places. So there we sat, looking out over the plaza to the tower and dome of the parish church of San Pedro, and behind it two Cerros, two mounts (not quite mountains but far more than hills). Looming before us was the Cerro Barreno, its shaded face murky and dun-green, its skyline a smooth bend against the blue desert sky, broken up, here and there, by the black silhouettes of some yuccas. To the immediate right of the Barreno and still catching some of that setting sun was the Cerro de San Pedro, loftier, broader. To the left, now looking down-valley, the distant lights of San Luis Potos are coming on through the city haze.

Juan Carlos had moved to San Luis Potos a year or so earlier, and he began to fill me in. Cerro San Pedro was the center and pivot of the local story. It had been settled in the late sixteenth century at the end of the war between the Chichimecas and Spanish. Thousands of people had poured into the area: Tarascos, Otom, Nahuas, Kongolese, Basques, Portuguese, Castilians, Andalusians. They had all come for the mines of Cerro de San Pedro. The mining boom gave rise to the city of San Luis Potos at the center of the valley, a city of indigenous barrios, a city of churches and convents, and now, over four centuries later, a city close to a million strong, sprawling across the Tangamanga valley, beautiful but also dusty, polluted, saturnine.

He also filled me in on the contemporary scene. A Canadian mining corporation had arrived to develop an open-pit gold and silver mine. It planned to raze the mountain of Cerro de San Pedro, engulf the two churches, and bury whatever remained of the village. That helped explain the graffiti spotted on the way inFuera Minera San Xavier!; Que Viva Cerro de San Pedro!; Neo-colonialismo. For Juan Carlos it was a provocation and an outrage. All this history destroyed. The death of Cerro de San Pedro, the cradle of the city and of the entire region, all so that some small group of foreign investors could reap a decades worth of dividends. And there was worse. The mine itself would consume massive amounts of cyanide and water, the former deadly, and the second, vital. In a dry city already facing failing supplies, he thought it unconscionable that a foreign corporation would put the valleys water at such risk. People had been fighting the project for years now. Up to that moment in late 2001, the company had still not been able to break ground and was running five years late. How long this stalemate would last was uncertain. The companys officers had recently met with Mexican president Zedillo in Toronto to work things out. If the Mexican government green-lighted operations, Juan Carlos and others felt that this would be the last mine. Given the scale and intensity of its devastation, the open-pit mine would finish the place off for good. Looking over to the Cerro de San Pedro, quiet and somehow watchful, the mountain seemed to pose itself as a riddle, one about how mining could give life to a place only to destroy it.

______

In less time than it has taken to write this book, the Cerro de San Pedro has been removed. It was shattered, dismantled, and then carted some five kilometers away to a leaching pad and refining plant that filched out the microscopic particles of gold and silver that it once contained. Half of the neighboring Cerro Barreno is also gone now. Its once clean arc of a skyline has been cut down to a ragged edge. Most of the town of Cerro de San Pedro has survived, barely. It currently perches on the edge of a steep pit hundreds of meters deep.

It took Minera San Xavierthe Mexican public limited company held by a succession of Canadian corporationstwelve years to reduce the mountain and gain its treasures. This is a remarkably short period of time given the scale of the task, but in the contemporary world of transnational mining, Minera San Xavier was well behind schedule. It had once announced the beginning of operations for 1996 and promised to be done within ten years. As it turned out, the social resistance to its operations stopped its advance for a decade. Work only began (June 2006) when it should have ended.