P.M.S.

Introduction

The

Shataka Trayam or

Trishati of Bhartrihari is among the best known and most quoted works of Sanskrit literature. The perennial interest it has attracted in India is evident from its many old manuscripts scattered across this country. The famous scholar D.D. Kosambi, who compiled its present critical edition, put their number as 3000, at a very conservative estimate. This new translation into contemporary English, here presented, is the latest in a list that goes back almost a century and a half in time.

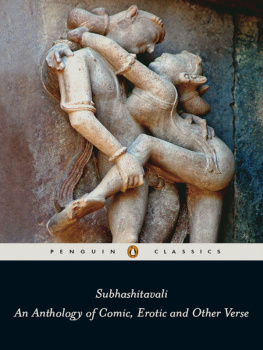

The works usual Sanskrit name, as given above, literally means three centuries, and indicates the numbers in its three components, each consisting of a hundred verses. All are subhashita or well said poetic epigrams. While the mood and thought of each lyrical, gnomic and mnemonic stanza is complete in itself, thus making an independent impact, their overall themes form a triad, and the whole is presented in three separate shataka s, each with its own title. The key words in these titles are Niti, Shringara and Vairagya respectively. They broadly reflect the politic, erotic and philosophic modes of thought and, in turn, focus on worldly life, pleasures in beauty, and a total abjuration of both. Some academics have also identified these elements with dharma, artha, kama and mokshathe four goals of human life in Indian thought.

In the present translation they have been rendered in brief as Life, Love and Renunciation. This work was described by its learned eighteenth-century Sanskrit commentator Ramachandra Budhendra as vidyavilasam or an elegant revel in knowledge; the description underlines its poetic aspect. To D.D. Kosambi, the crisp and polished stanzas reveal a great poet... few can exceed the force of his epigrams... and the finality with which a sentiment is rounded.

Many modern scholars have noted that this poetry manifests an inner tension and contradiction. The well-known Austrian Sanskritist M. Winternitz described this as an oscillation of the Indian mind between sensuousness and renunciation. These tensions have also been explained in social and ideological terms. Bhartriharis modern compiler, Kosambi, was both an eminent scholar and an ideologue who dedicated his critical edition of these poems to the memory of Marx, Engels and Lenin. He saw them as a physiognomy of a whole class, and noted their acute observation of human nature and distress experienced by a man of letters without some means of livelihood.

It is a poetry of frustration, he wrote, which provides at most an escape, but no solution, and the poet is unmistakably the Indian intellectual of his period, limited by caste and tradition in fields of activity, representing a cross-section of Indian intelligentsia of an age that has not yet passed away. Kosambis view received an appropriate comment from his own erstwhile colleague at Harvard, Sanskritist D.H.H. Ingalls. In his review of the formers critical edition, Ingalls wrote that the perception in it explains the mood but does not explain the expression. Beethoven too was a hanger-on at rich mens houses, and singularly frustrated. He added that the poetry of Bhartrihari remains beautiful and sometimes truly great.

As for the timeless human tensions it reflects, these would be clear to any reader of the present translation, though their underlying causes may be varied. From the poetry one must now turn to the poet. As with many ancient writers in Sanskrit, there is little definite information about Bhartrihari. His dates, times and personal details still fall in the realm of speculation. Kosambi outlined four theories on the subject, derived from different traditions about the name. In this theory, as well as in the fourthwhich describes him as the elder half-brother and predecessor of the legendary King Vikramaditya of Ujjainhe renounced the throne after discovering that his beloved wife was unfaithful to him.

The deep disenchantment this caused him is expressed in a well-known verse from the Kosambi compilation, included as the sixth in the Prologue of this translation. Commenting on all these theories, Kosambi opined that there is nothing to prove that the poet was other than a learned man, hungry and in distress. As for his dates, a recent study indicates the current consensus among scholars that Bhartrihari should be dated to 450500 CE . This new translation endeavours to present the verses of the Shataka Trayam in contemporary language for modern-day readers. Their Sanskrit originals are drawn from Kosambis definitive critical edition mentioned earlier. That savant stated that in preparing it he studied various versions as given in 377 different manuscripts, and noted in them a total of 852 individual stanzas.

To identify the 300 originals as far as possible, he divided these verses into three groups: the first comprised 200 stanzas generally found in all versions; the second, 152 stanzas not found in all versions; and the third, 500 stray verses from only single versions. In the first group, moreover, vv. 876 were under the heading Niti, vv. 77147 under Shringara, and vv. 148200 under Vairagya, while vv. 18 of his compilation are not under any single heading.

He also reproduced another 187 verses which he described as apocryphal and outside the compilation. The present translation includes all 200 verses of Kosambis first group, though their order has been altered slightly for better reading. To complete the totality of three centuries, other verses have been taken from the second and third groups, as also found in Subhashita Trishati, the eighteenth-century compilation by Ramachandra Budhendra that Kosambi considered about the best of its kind among those known. Their placement in this edition is also generally in line with that in Trishati. In addition, some popular verses found in both Kosambi and Budhendra have been included in the Prologue of this translation and the Miscellany at its end. Within each of the three main sections, sub-headings, mostly drawn from Budhendra, have been inserted for clarity. The bracketed numbers given at the end of each verse (right-hand bottom) are from the Kosambi compilation, added here for ready reference to the original text.

Translating the centuries of Bhartrihari has been a memorable experience for me. The verses are replete with succinct thoughts and sharp images. Their tone ranges from cynical to wishful, from erotic to didactic, from pensive to completely detached. Their expression is sometimes personal, at others all-embracing, and occasionally tongue-in-cheek. Their language is generally simple and clear. Some give vivid glimpses of the poets personality.