Table of Contents

Introduction

We can't prevent the birds of sorrow from landing on our shoulder.

We can prevent them nesting in our hair.

Old Chinese proverb

This book was written to help adults who care for or work with children who have been bereaved or who are facing the death of someone close to them.

I acknowledge that some of the adults may also be bereaved and are having to cope with their own grief as well as supporting their children. Other adults, maybe professionals working with children, may find that the child's grief awakens unresolved grief within themselves. Others' response may be that they don't know what to say and therefore say nothing, leaving both themselves and the bereaved child feeling isolated.

Fear and feelings of inadequacy can stop adults from helping their children come to terms with the fact that loss and bereavement are an inevitable part of our lives. Death is still a taboo subject in our society and, while not wanting to go back to Victorian times when death and mourning was very public, I feel it is so important that we help our children both face and cope with such a powerful event in their lives.

This is not an academic tome but a straightforward explanation of how children might feel and behave and the issues that might be involved. It offers practical advice and strategies to help you to help children confront and deal with troubled feelings. No one need be an expert in these matters - the reader does not need professional knowledge, but merely compassion and a desire to help.

Each person's grief and how they express it is individual to them. Other factors such as developmental stage, culture, belief, experience and nurture also come into the equation. When you read this, please take into account how you feel about a strategy or an approach and consider how suitable you feel it is for the child you are with.

Grief brings change. A grief resolved - that is, fully experienced and expressed - can be integrated into a person's life experience and help them treasure fond memories and move on. It can enable that person to have an increased understanding and compassion for others and take life as it is, with all its sorrows and joys.

Finally, nobody is perfect and we can only do our best. Just open your heart to your child, and show that you care and are alongside them at this difficult time.

CHAPTER 1

Talking with Children when Someone Dies

Give sorrow words

The grief that does not speak

whispers the o'er fraught heart,

and bids it break.

Macbeth, William Shakespeare

Accepting a child as a bereaved person

The most important point for adults to realise is that children do grieve, whatever their age. Some adults may recognise this but believe that they are 'protecting' them by not discussing such a powerful topic.

Adults who set out to protect children from the realities of death may:

- not talk about the death;

- not show any emotion in front of the child;

- pretend that all is normal;

- make sure that the child is not present at or involved in any ritual.

'When my grandfather died I was only five and remember being told to go and play in the garden. I sat on my swing thinking about my grandfather, feeling that I mustn't cry and wondering why I was excluded from all the support that was going on indoors with the adults.'

(Adult dealing with unresolved grief)

This kind of behaviour confuses children and is very likely to make them feel excluded. Even years after a death, adults can feel angry about being excluded:

- 'Why was I sent to my friend's house when my mum died and had her funeral? I never had time to say goodbye.'

- 'If I had known that my sister was so ill, I would have wanted to go and see her more.'

Children will pick up on what is not being said or done, and will take their cue from the adults around them.

Children who feel excluded from a family bereavement may:

- not cry in front of the family;

- bottle up feelings;

- feel unable to ask pertinent questions;

- feel excluded and confused;

- imagine far worse things.

Guy Perkins' poem, 'Small Talk' reproduced below deals with this issue very effectively. He describes normal events happening around a grieving child who wants to be able to talk about his or her grief.

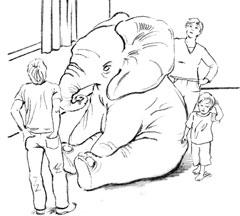

Describing grief as like an elephant in the room, which everyone is aware of but is trying to ignore, has become a common image since the publication of Terry Kettering's poem 'Elephant in the Room'.

'It helps to know why someone in the family is sad or worried. If you don't know, then you think that you're to blame or that it is worse than you thought. I felt so alone when my grandma died as no one spoke about it to me. Conversation stopped when I went into a room and no one talked to me about it or asked me how I felt.'

(Girl, aged 12)

Children who grieve alone or who bottle up feelings when someone significant to them dies will almost certainly have to deal with unresolved grief at a later time. Adults need to realise that children will naturally be upset, will need to be allowed to grieve and helped to express and deal with it, and must be part of the bereavement process.

Small Talk

Your knock wakes me and Tabby,

You give us both a pat.

The telly's on for breakfast,

The cat sits on the mat.

This horrid thing inside me

Is growing awfully fat.

You never say her name now

And all I hear is chat.

Small talk.

My friends at school are wary,

My teachers cut me slack.

They don't know what to say,

So I sit right at the back.

The thing inside weighs heavy

With questions I can't ask.

I walk around the playground

Voices shouting at my mask.

Small talk.

This ache inside my stomach

Is tearing me apart.

This monster of unknowing

Lies clamped around my heart.

Oh PLEASE just let me ask you,

I know you're also sore.

You raise your head, it's time for bed,

You squeeze a smile and feed me more

Small talk.

Guy Perkins

Breaking the news

Who?

Breaking the news of a death in the family should preferably be carried out by the adult or adults who are emotionally closest to the child. However, it is possible that in some situations this person is so grief stricken that some other close relative or friend may be the right person to talk to the child.

Where?

If possible, take the child to a quiet place where you will be undisturbed and comfortable. Sit yourself and the child down before you speak.

How?

Make sure you are as composed as possible and that you have the child's full attention. The exact words you use will depend on the stage of development of the child, the circumstances of the death and your relationship with the child, but start by saying you have some sad news you must tell them.

- Be as honest and open as possible and try not to use euphemisms - 'gone to sleep', 'passed away', 'lost' - that may confuse the child. Be direct and say that the person has died/is dying.

- Allow time and be prepared for a variety of reactions. If you have the opportunity, convey to the child that there is no set or 'correct' way to react.

- Children may be shocked or show disbelief. They may cry or be full of despair. Some may be quiet and stunned. Others may show what might seem inappropriate reactions, such as saying 'What are we having for tea?' and continuing with their usual activities. Usually children will ask questions, either straight away or on another occasion.

Next page