Contents

List of Figures

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

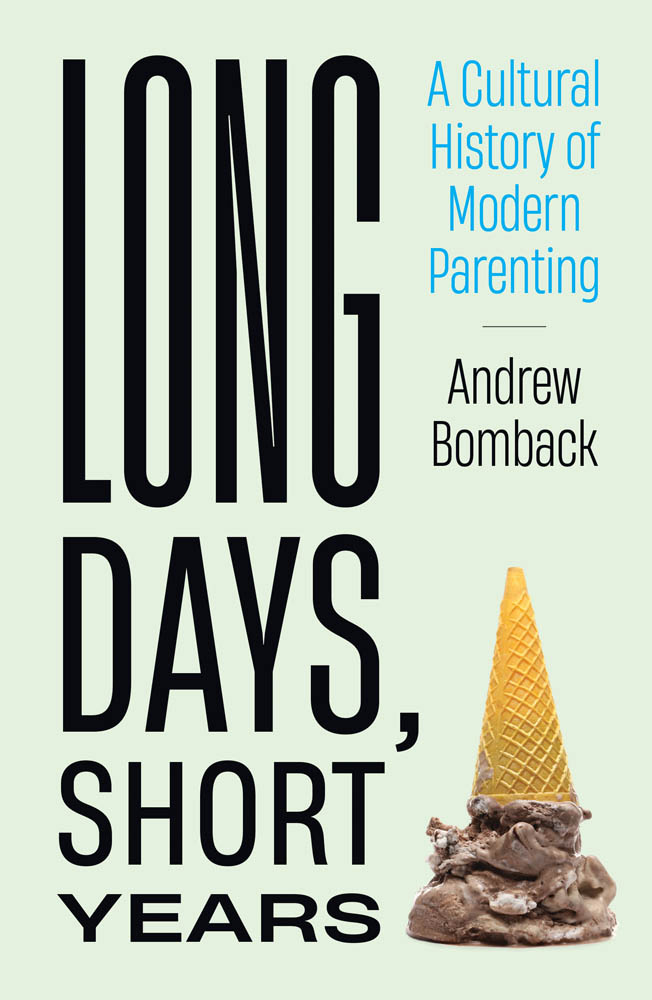

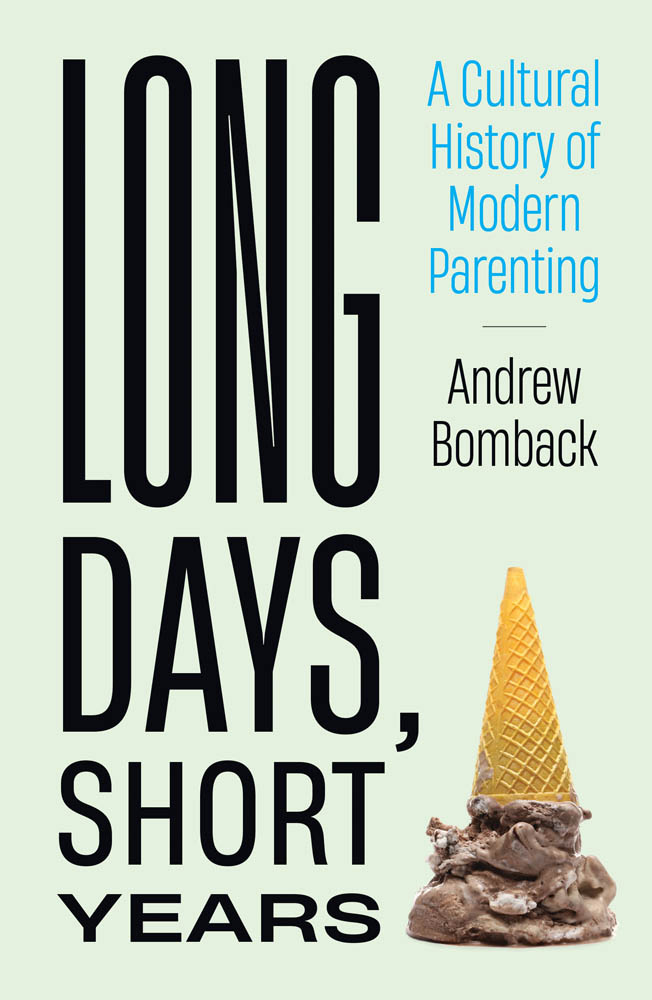

Long Days, Short Years

A Cultural History of Modern Parenting

Andrew Bomback

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts|London, England

2022 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bomback, Andrew, author.

Title: Long days, short years : a cultural history of modern parenting / Andrew Bomback.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021047583 | ISBN 9780262047159 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Parenting, | Child rearing. | Parent and child.

Classification: LCC HQ755.8 .B646 2022 | DDC 649/.1dc23/eng/20211001

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021047583

d_r0

To my family

All the years of ritualundressing and dressing, diaper changes, potty time, bath time, tooth brushing, reading, hugs and kissesare so exhausting. If they dont fall asleep beside him, whoever is on bedtime duty stumbles downstairs, announces wearily, And that concludes todays parenting. Until the next day, and the next and the next. As if it were a curse and not a blessing. As if it really were forever.

Peter Ho Davies, A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself

Contents

List of Figure

The Google Books Ngram Viewer charts the frequencies of any set of search strings using a yearly count of n-grams found in sources printed since 1500 in Googles text corpora in English, Chinese, French, German, Hebrew, Italian, Russian, and Spanish. The x-axis denotes the year in which works were published; the y-axis shows the frequency with which the n-gram appears throughout the corpus. This usage graph plots the abrupt rise of parenting in works published between 1970 and 2000.

Authors Note

My neighbor, Frank, a clinical psychologist, recently published his first book, The Fear Paradox. In its opening pages, he quotes Franklin Delano Roosevelts famous lines about the nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror that paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance, primarily to point out that his book does not aim to free its readers from this paralysis. That is what countless self-help books attempt to free us from, he writes. But what I have come to wonder about is why fear is so difficult for us in the first place. He advises his readers to approach this material not as a how to but rather as a how come book.

Over the years, Ive borrowed gardening tools, baking ingredients, and bridge tables from my neighbors, and here Id like to borrow Franks phrasing. I am in no position to write a how to book on raising children. While I am a father, I am not a particularly good one, as I will confess throughout this book. In fact, I set out to write this book because I was struggling so much with my parenting. Years earlier, facing down a midcareer crisis as a physician, I wrote a book dissecting what exactly I and other doctors did each day, hoping to better understand why Id chosen this profession and figure out whether and how I could continue in the field. I was in a similar crisis when I began writing this book. I knew why Id chosen parenthood but worried about how I was performing in the task and whether this performance would ever improve. I hoped that analyzing what it meant to be a parent today might give me some insight into what I was doing wrong and what, potentially, I could do right for my family. And I sensed that many other parents were staring down the same question that I wasnamely, how come this is so hard?

My book on doctors was called Doctor, and I originally titled this book Parent. I realize I can be accused of a lack of imagination, but in my mind there was an important distinction between the two titles. I was using doctor as a noun and parent as a verb. As I will discuss in the forthcoming pages, the verb form of parent is a relatively new entry in our collective lexicon, and not a particularly salubrious one. With the exception of chapter 9, this book makes no attempt to dole out advice on how to parent. Throughout, though, I try to address the question of how come it can be so much fun to be a parent and yet so incredibly frustrating to parent.

Parenting is an emotional subject. I expect the vast majorityif not allof those who read this book will be parents or caregivers with some skin in the game. In some ways, how a reader feels about the subject of parenting, even as an academic topic, cannot be divorced from how a reader feels about their own parenting. I do not intend this to be a controversial book, but I also understand that some of the subject matter may elicit strong reactions. One of my central themes is that anxiety plagues modern parents, which can be a difficult pill to swallow (even if youve read The Fear Paradox). I explore this and other themes with reviews of historical trends, dissections of popular culture, interviews with other parents, and, throughout, my own parenting stories. I intend these bits of personal memoir to open up spaces for others to reflect on their own challenges and opportunities as parents. I also intend these stories to highlight how, in my own life, I evaluate parenting with curiosity and respect. I have tried to approach all of the material in this book with that same curiosity and respect.

I recognize that I am not the conventional messenger for this material. I am a physician, but one who specializes in rare kidney disorders in adult patients. I am an academic, but my research is focused primarily on evaluating novel treatments for these rare kidney disorders. Therefore, I have been cognizant throughout the process of creating this book that I am, in many ways, an outsider to the material, despite having a house filled with small children. I have been fortunate to rely on the work of others who are more conventional messengersparticularly two recent histories of parenting, Jennifer Traigs Act Natural I strongly encourage readers to seek out these and other works cited in my endnotes for alternative versions of this subject matter.

I also recognize that I am able to approach this material from a place of privilege. Not only am I a card-carrying member of the WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) demographic, I also am a white, straight, cisgender, able-bodied man. The WEIRD demographic has both produced and consumed a substantial chunk of the parenting literature, and yet this same demographicespecially WEIRD mentoo often view parenting as something that other people should do for them. The male voice in the parenting sphere is unusual; when it does appear, its more likely to tackle the subject from a humorous rather than a serious perspective. While I have intended my analyses to be objective and, save for some specific subject matter (e.g. chapter 5), gender-neutral, I am not naive enough to believe that readers will forget that I am a man writing about a verb with different expectations for moms than dads. I hope that an honest and humble accounting of my efforts to understand this subject matter is the best way to ensure that I am not running the risk of mansplaining parenthood. In addition, whenever possible, I have aimed for primary sources that are not penned by white, straight, cisgender men like me.