All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Crown and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

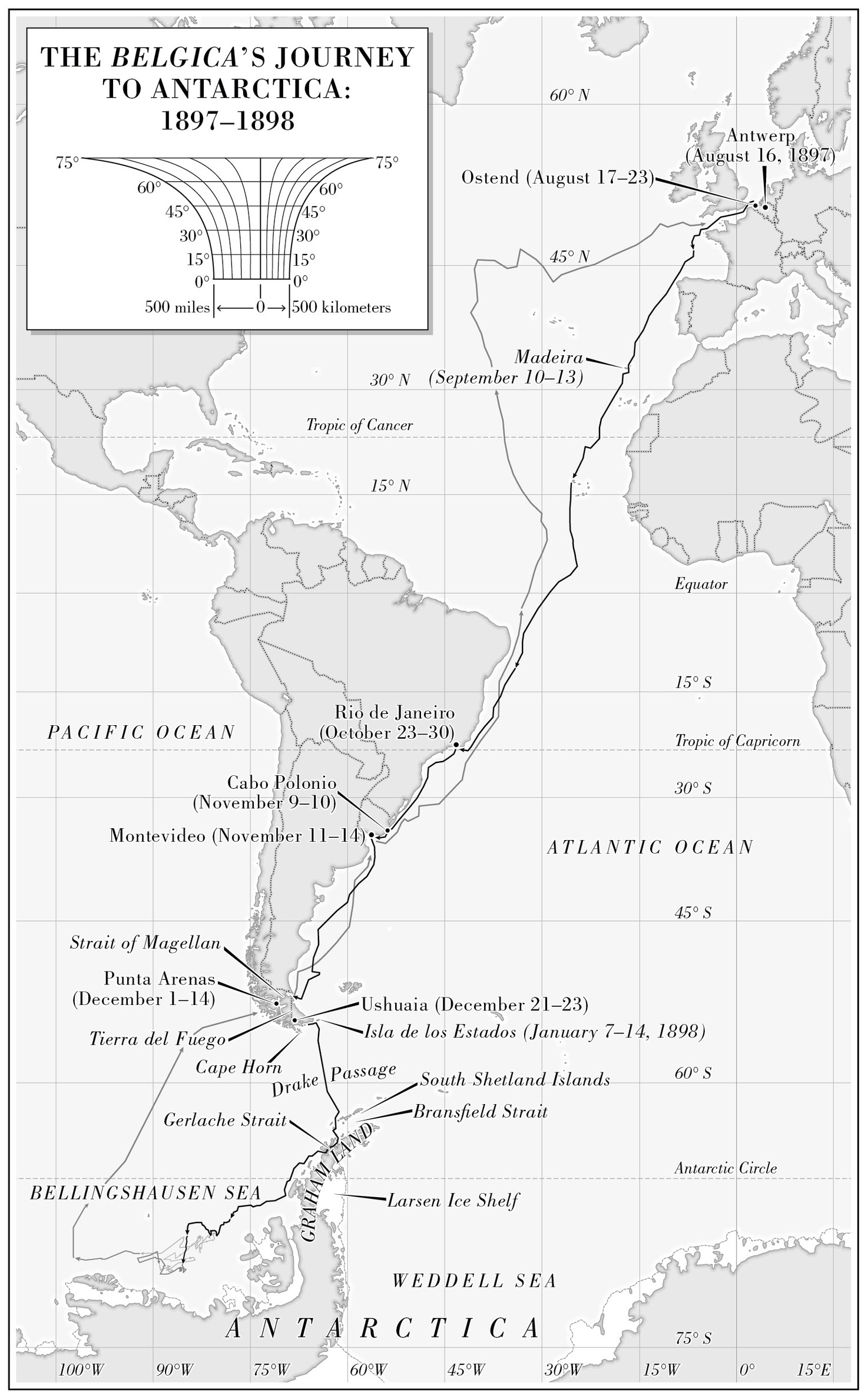

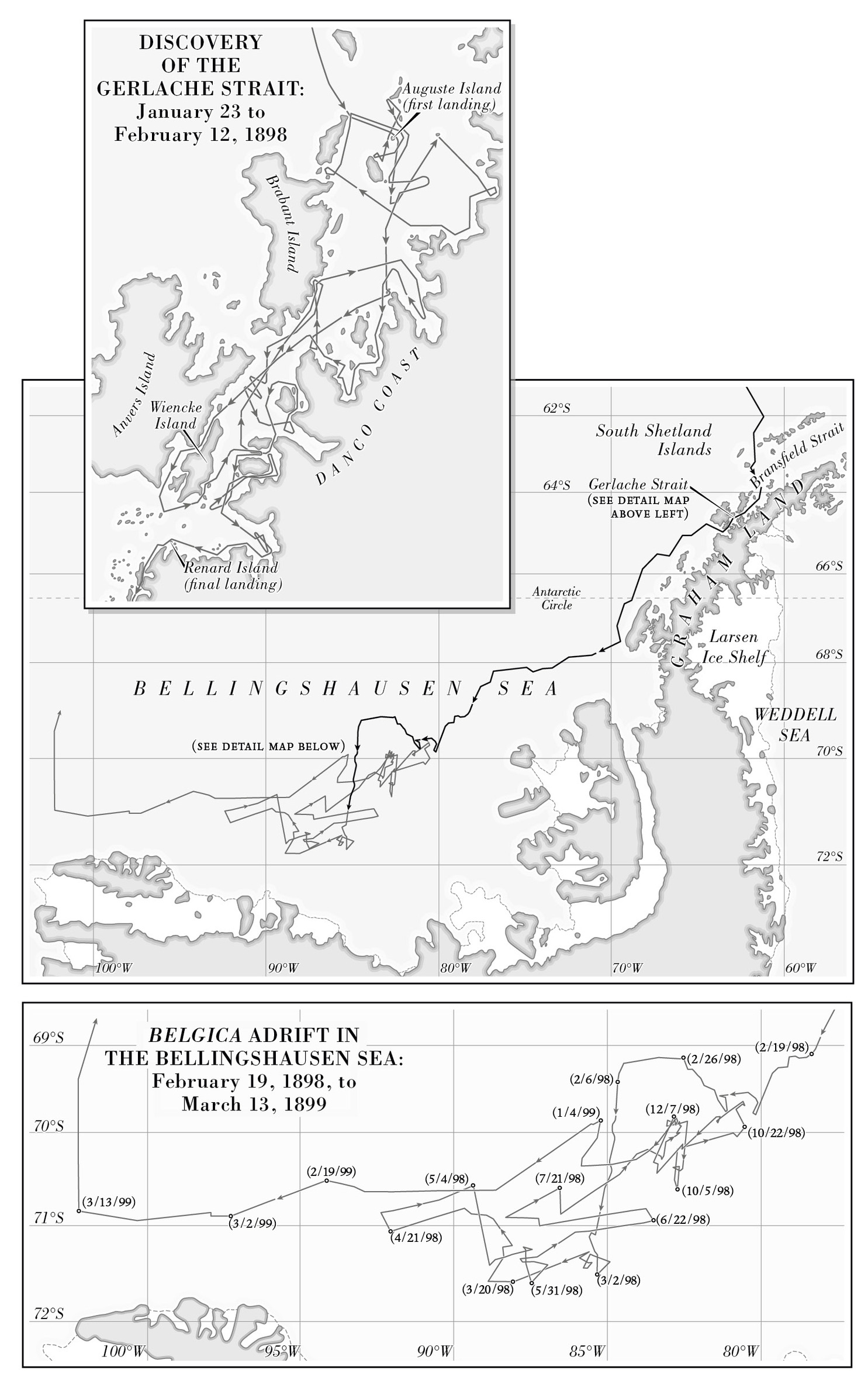

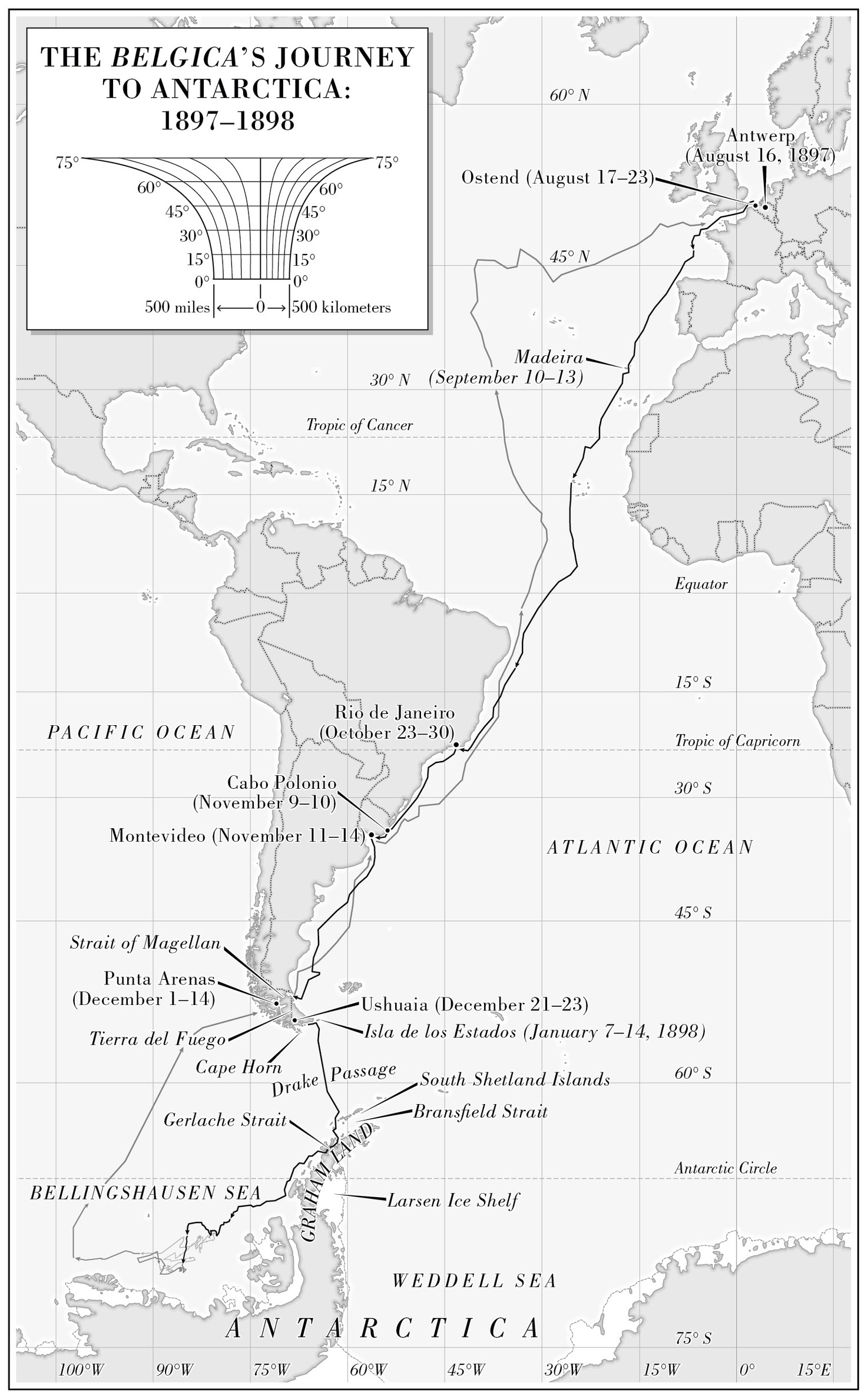

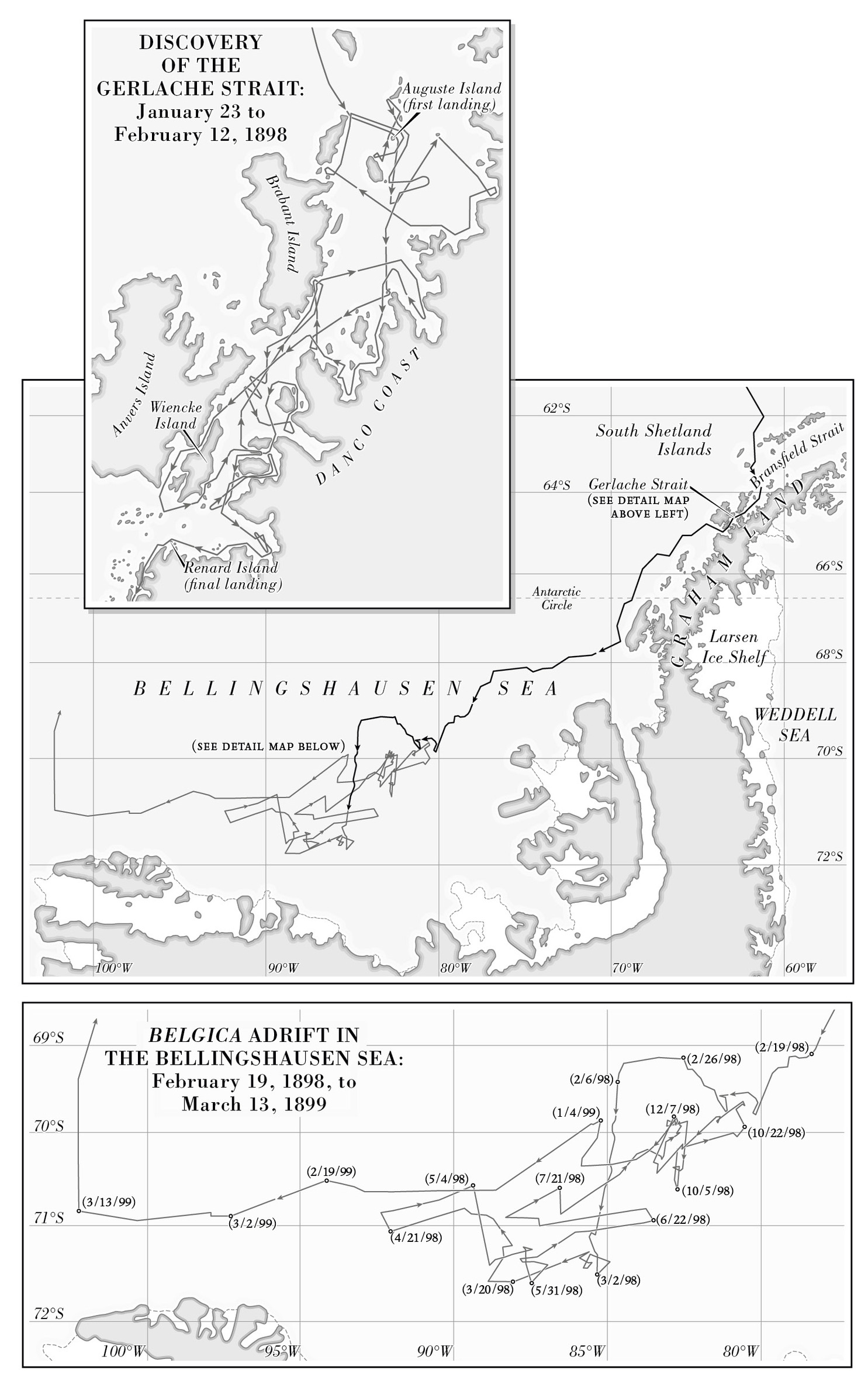

Maps copyright 2021 by David Lindroth, Inc.

PROLOGUE

JANUARY 20, 1926

LEAVENWORTH, KANSAS

The light of a cold gray dawn filtered through the grating that covered the narrow windows of the Leavenworth penitentiary hospital. Exhausted after his sixteen-hour shift, the old doctor tidied his station and signaled to the guard that he was ready to be escorted to his cell. When he passed his duties off to the regular prison physician, he became just another prisoner, inmate #23118.

The doctor collapsed on his bed. It had been a long night. The country was then in the grip of an opiate epidemic of unprecedented scale, and after dark the top floor of the hospital became, in the doctors words, a narcotic mad house, as addicts in the agony of withdrawal howled for a fix. The doctors cell was a well-lit room within the three-story brick building. It had a single bed, a chair, and running water. On the walls were elaborate needlework pictures he had made. His were more comfortable accommodations than those afforded to some of his contemporaries in the prison, including the Chicago gangster Big Tim Murphy (who had become a friend and protector) and, later, Carl Panzram, the prolific and unrepentant serial killer (who would not). But then, inmate #23118s offenses were of a different nature. The sixty-year-old had been convicted of fraud in connection with what amounted to a pyramid scheme involving stock in an oil company. He was on year three of a fourteen-year sentence, a punishment far harsher than that usually doled out for similar crimes, but one in proportion with his notoriety.

In his half-remembered youth, long before his fall from grace, the doctor had been a celebrated polar explorer. His claim to have conquered the North Pole in 1908 had made him a national hero until it was suspected that he had falsified that feat, among several others. He will count for ever among the greatest impostors of the world, The New York Times would assert. That and not the discovery of the north pole shall be his claim to immortality.

In the afternoon, a guard informed him that he had a visitor. Since entering prison, the previous year, the doctor had refused to see friends and family. The man waiting for him today was perhaps the only person alive for whom he was willing to make an exception. Rarely a day passed when the prisoner didnt think of his former comrade, a strapping, fifty-three-year-old Norwegian with whom he had served on a harrowing expedition to Antarctica nearly three decades earlier. Once the doctors apprentice in polar matters, the Norwegian had gone on to become one of the greatest explorers the world had ever knownthe legitimate conqueror of the South Pole. His headline-grabbing exploits, and the apparent ease with which he accomplished them, had conferred upon him an almost mythic aura. An international lecture tour had taken him through the United States, and he had made it a point to pay his respects to his former mentor.

News spread that the illustrious explorer was meeting with Leavenworths best-known inmate, and within minutes reporters swarmed to the prison. With this public gesture of support for the discredited doctor, the Norwegian was risking his own reputation. But the visit was not merely an act of pity for an old friend in need. Years of single-minded competition for the planets most coveted geographic prizes had taken their toll. The fire within him had burned him up. He had grown bitter and paranoid, with few friends who understood him as well as the doctor from whom he had learned so much in simpler times, when all that mattered was survival. Above all, the Norwegian felt honor-bound to visit the man he credited with saving his life.

The two mens fates had diverged dramatically since theyd last seen each other, and it showed on their faces. Imprisonment had drained the doctor of color and vitality. His slate-hued eyes had lost some of their electric quality, his once luxuriant hair had thinned, and his large nose had, if possible, grown even larger. But there was a flash of his younger self when he smiled, revealing several gold teeth.

The Norwegian visitor towered over the doctor. His face was brown, deeply burned from polar snows, lined with deep wrinkles and a pleasing fresh vigor, the doctor later recalled. The explorer was at the apex of glory [while] I was in the ditch of penal condemnation.The effect to me was at first appalling, but soon old cordiality burned all barriers. We were as brothers.

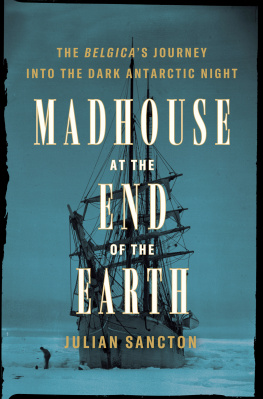

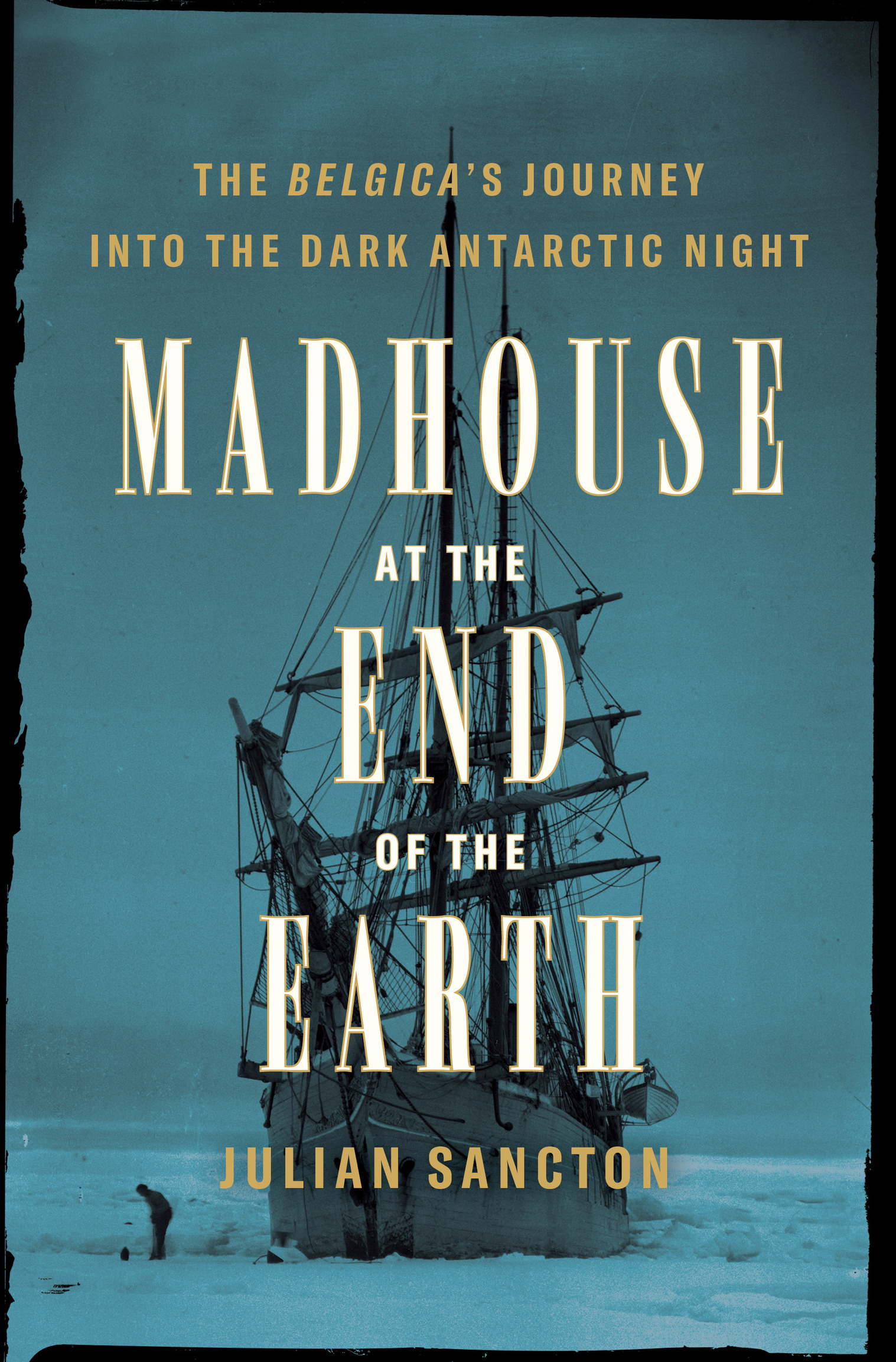

They grasped each others hands and didnt let go. To confound the eavesdroppers, they began to speak in what the doctor described as the mixed lingo of the Belgica. The Belgica was the ship on which theyd met, in the prime of their lives, on their first journey to Antarctica. The various languages spoken by the scientists, officers, and crew blended into one Babel-like amalgam of French, Dutch, Norwegian, German, Polish, English, Romanian, and Latin. The voyage taught both men how the cold and the dark can ravage the human soul. It was on this expedition that the doctor had come to worship the sun. Then, too, he had been a prisoner, held captive not by bars and locks but by an infinite expanse of ice. Then, too, he had heard shrieks in the night.

CHAPTER 1

Why Not Belgium?

AUGUST 16, 1897

ANTWERP

The river Scheldt wound languidly from northern France through Belgium, taking a sharp westward turn at the port of Antwerp, where it became deep and wide enough to accommodate oceangoing ships. On this cloudless summer morning, more than twenty thousand people flocked along the citys riverfront to salute the departure of the Belgica and exult in its glory. Freshly painted steel gray, the 113-foot-long, three-masted steam whaler, fitted with a coal-powered engine, was headed to Antarctica to chart its unknown coasts and collect data on its flora, fauna, and geology. But what drew the crowds today was not the promise of scientific discovery so much as national pride: Belgium, little Belgium, a country that had declared its independence from Holland sixty-seven years earlier and was thus younger than many of its citizens, was staking a claim to the next frontier of human exploration.