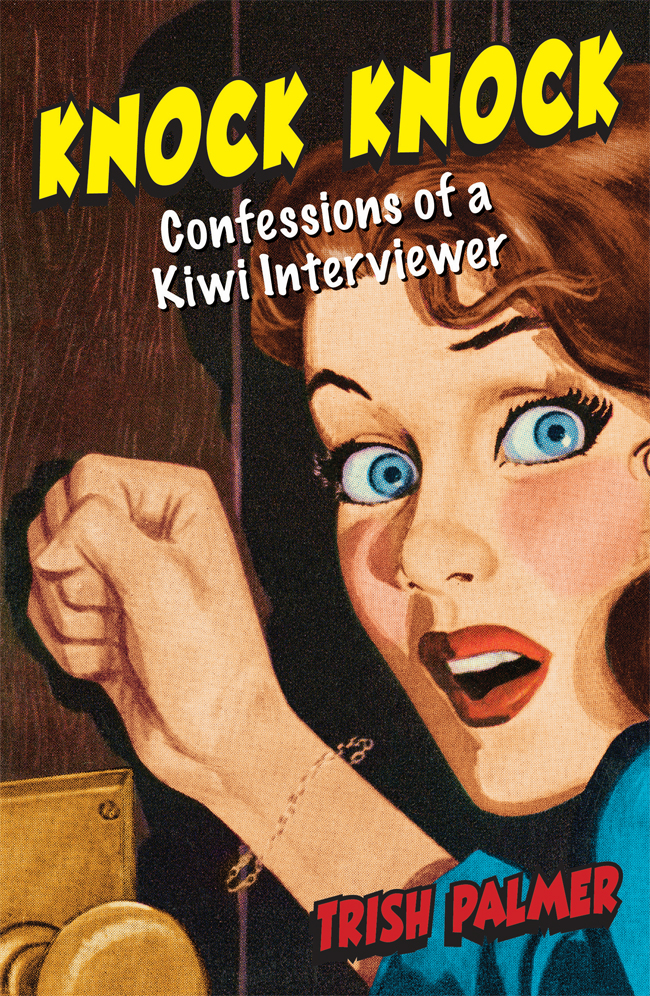

KNOCK KNOCK

KNOCK KNOCK

Confessions of

a Kiwi Interviewer

TRISH PALMER

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

ISBN 978-1-990003-21-9

ePub ISBN 978-1-990003-27-1

Mobi ISBN 978-1-990003-28-8

An Upstart Press Book

Published in 2021 by Upstart Press Ltd

BDO Tower, Level 6/19 Como Street

Takapuna, Auckland 0622, New Zealand

Text Trish Palmer 2021

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Design and format Upstart Press Ltd 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Designed by Nick Turzynski, redinc. book design, www.redinc.co.nz

Printed by Everbest Printing Co. Ltd., China

Contents

I ts been an exhausting week; you are luxuriating in a rare moment of peace and quiet at home, when theres a knock on the door. Unbelievably, its someone doing a survey. Really? Now? Your first instinct is to tell me to go away. When I approached your door, I was wondering if this is where I get locked in the kitchen (again), abused (by a parrot), or left holding the baby (literally). Will you be clothed, or stark naked (yes, it happens); all I want is for you to just take part in this interview so that I can stop for lunch, please! Our eyes meet: yours resigned, mine hopeful. Here we go...

Welcome to my world

I have been an interviewer for over 25 years, mostly door knocking or phoning folk to get their opinions on a myriad of local, national or international issues. Everything from how satisfied you are with your water supply and footpaths to measuring a representative sample of the nations ability to read and do maths. Going into peoples homes is an absolute privilege. Hearing your stories has been an amazing, and sometimes challenging, experience. I am visiting you as an observer, but sometimes I come away frustrated that I am unable to help. More often than not, though, you have lightened my day. Every contact has taught me something, not least that we are a diverse and fairly resilient bunch. Also, that most folk are lovely, and that there is no such thing as normal.

Naturally, some encounters stand out, whether its due to the person, their home, or their circumstances and, occasionally, due to the fear I suffered...

The house looked shut, with old, faded blinds falling apart behind dirty windows, peeling paint on rotting weatherboards, and weed-covered broken paths. Therefore, I was surprised when not only was there an inhabitant but that he agreed to be interviewed, inviting me in. His closed secretive aura did not suggest a welcome of any sort, and he inspected me closely while I introduced myself. His come in was barely an invitation, but I was there to do a job, so in I went.

Stepping into the dark and dingy kitchen, I heard a very distinctive sound behind me; he had locked the door. Terror hit my stomach with such force I thought I was going to vomit. Panic threatened to take over. I was interviewing in a hilly suburb where the residents could see each other, but no one would be looking my way. There was no chance of being heard; the houses were too far apart for noise to travel reliably. The isolation, despite me being able to hear traffic below, was very real.

With huge self-control I stuck to the tricks Id learned years before. Outwardly pretending nothing was untoward, I sat at the dining chair nearest the door, inviting the man to sit opposite me, and proceeded with the interview. Inside I felt like a mouse, playing catch-me-if-you-can with a very large cat.

As usual, I was wearing sensible flat shoes, and carrying as little equipment as possible, not just for comfort but for safety. Escape is more likely if you can move easily.

The man had a very stand-offish approach to the questions, and he outright refused to answer anything that required an opinion. His answers suggested that he had virtually withdrawn from society. I noticed that there were no photos or pictures anywhere in the room, not even a calendar. A single lightbulb hanging above the sink tried to light the room but failed.

He asked me how Id chosen him, where I lived, did I have family, and, chillingly, who knew where I was. When respondents ask questions, and many do, I always answer honestly; how can I expect them to take part in the survey if Im not prepared to be upfront with them? However, my answers vary from being brief and vague through to full detail, depending on the circumstances. Sometimes sharing a wee bit of myself helps establish rapport and trust, which are vital for a worthwhile interview.

Sitting in that locked room, I answered truthfully but kept the details vague, except for one item which I made explicitly clear the bit about leaving a note for my husband each day outlining precisely where I would be working. This is a safety practice Ive always done, so that at least police would know where to start looking if something went wrong. Sitting in that mans kitchen, I was certain that the day had come.

The interview seemed to take forever; I was worried that my fear would show. At intervals I surreptitiously glanced around the room, noting where potential self-defence tools might be found, all the while earnestly being the professional interviewer. I took the opportunity of a supposed coughing fit to turn and take a look at that exit door and lock; thankfully the key was in its place.

With the interview nearing its end, I organised my gear for a quick exit. Still talking, before the man could realise we were done, I was out of that chair, turning the key, and out the door. Fresh air never felt so good!

As I breathed in, a hand touched me on the shoulder, scaring me half to death. I turned, facing the man, who looked at me without threat and quietly said, Thank you, no one has visited me for years. He turned and went inside, locking the door behind him. My heart broke for this lonely man, locked in his silent world. How I wished Id left something behind so that I had an excuse to knock on his door again.

Even in the same street there can be a wide variety of people and experiences. In one middle-class suburb I met someone who had walked through Asia, yet further on there was a resident who had never been out of their own region and had no interest in travelling to explore the other main island of New Zealand.

Every day, interviewing is a voyage of discovery; not only finding valleys, streets and parks that I hadnt known existed, but also meeting ordinary folk who have done, or are doing, extraordinary things, with resilience, courage, kindness and positivity.

Theres the neighbour who runs errands for the housebound, the retired couple voluntarily welcoming local kids to their table after school each day to help with homework and make sure that simple needs like clothing and food are met, the lady knitting for charity, the mum caring for her severely handicapped son, the frail gent making his wife a cup of tea, the busy mum coaching her sons soccer team, the dad ignoring his cell phone in order to read his daughter a story, the couple who had put their New Zealand lives on hold to work for Habitat for Humanity in a poor region overseas; the list goes on and on.

Some folk, of course, dont have the resources to help others, yet they too are amazing. For instance, the solo dad trying his very best to give his children a good start in life. He was learning to read so that he could help his kids with homework. How difficult would it have been to front up, admit the gap, and ask for lessons? He was looking forward to being able to read school newsletters, text friends, enjoy community newspapers, and maybe even get his drivers licence, though he didnt think hed ever be able to afford a car. He was also hoping to be able to read and understand the many official forms that hed had to sign over the years: tenancy agreements, enrolment forms, custody papers, bank letters. He said he wanted to be a good dad one day. Looking at his healthy, happy, polite kids, it was clear that he already was.