Patricia Harris and David Lyon are frequent contributors to the Boston Globe and authors of more than thirty books on travel, food, and art. Their most recent title is Historic New England: A Tour of the Regions Top 100 National Landmarks, also published by Globe Pequot. This volume continues the exploration of places and people who have helped shape the region. Harris and Lyon live in Cambridge, Massachusetts, within walking distance of Harvard Yard. They make their online home at HungryTravelers.com.

We would like to thank editor Amy Lyons for her enthusiasm for this project and the staff at the Globe Pequot Press for wrestling our manuscript into the book you have in your hands.

When we began this project, we had no idea that within weeks we would be engulfed in the lockdowns and closures of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet time and again the staff and volunteers associated with Bostons National Historic Landmarks stepped forward to assist us with our research. Some of them even let us in the doors so we could refresh our memories and document properties in photographs. Quite literally, this book would not have been possible without them.

Finally, we are indebted to the readers of Historic New England, our preceding book about the regions National Historic Landmarks, as well as to those who turned out to our readings and talks, often arranged by local librarians. Your enthusiasm was so contagious that we were encouraged to write this follow-up title. Thank you, one and all!

Bordered by Tremont, Park, Beacon, Charles, and Boylston streets; friendsofthepublicgardenr.org; open year-round; free. T: Park, Boylston

Boston was only four years old when Boston Common was established in 1634. Puritan settlers purchased the land from William Blackstone. The Anglican minister and hermit was the first European to lay claim to the area after the Massachusett tribe had abandoned their settlement during the 1616-19 Great Dying.

History records that each homeowner chipped in six shillings toward the purchase price of thirty pounds. The Founders Memorial along the Beacon Street edge of the Common depicts Blackstone welcoming John Winthrop, Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, to the Shawmut Peninsula. Erected in 1930 to mark Bostons tricentennial, the monument also records Winthrops aspiration that the new town shall be as a city upon a hill.

It is hard to tell what thirty British pounds might equal in todays currency. But there is no doubt that the savvy settlers got themselves a good deal. The 50-acre park is the oldest in the country and remains the green heart of the city, the place where all its residents and its visitors cross paths.

It is impossible to imagine the history of Boston without Boston Common. Following the English model, the land was originally set aside as a commons to be equally shared by all residents of the community. Its principal use was as a military training field and as pasture for the towns herd of seventy milk cows. Properly speaking, it is the Common or Boston Common, but never the Boston Common.

Other uses soon intervened. The cattle had to make room for whipping posts, pillories, and stocks to punish those who went against the order of the Puritan leaders. More serious offenders, including murderers, thieves, witches, pirates, and even Quaker religious dissenters, met their deaths by hanging from the so-called Great Elm that an 1876 storm finally destroyed.

It was inevitable that the Common would be a stage for events leading up to the Revolution. Patriot Samuel Adams gathered crowds to rail against mistreatment by the British crown. With trouble brewing, British regulars established an encampment on the Common in 1768. At the time, the waters of the Charles River rose to the edge of the Common on the Charles Street side at high tide. Thats where the British troops boarded boats to cross the river and begin their march on Lexington and Concord and, two month later, their assault on Bunker Hill (see page 85).

Many of those soldiers rest in perpetuity in the Central Burying Ground on the Boylston Street side. Established in 1756, it was Bostons fourth graveyard. Painter Gilbert Stuart, most famous for his 1796 unfinished portrait of George Washington reproduced on the $1 bill, is also buried here. Entry into the burying ground is through a small gate on Boylston Street near the Tremont Street corner.

Some of Bostons most luxurious mansions were rising on Beacon Hill by the early nineteenth century, making it Bostons most prestigious address. By 1830, cows were no longer welcome as the Common completed its transformation from pasture to park. Crowds delighted at balloon ascensions and early football games, but the Common also turned to the serious business of hosting anti slavery protests and Civil War recruitment rallies.

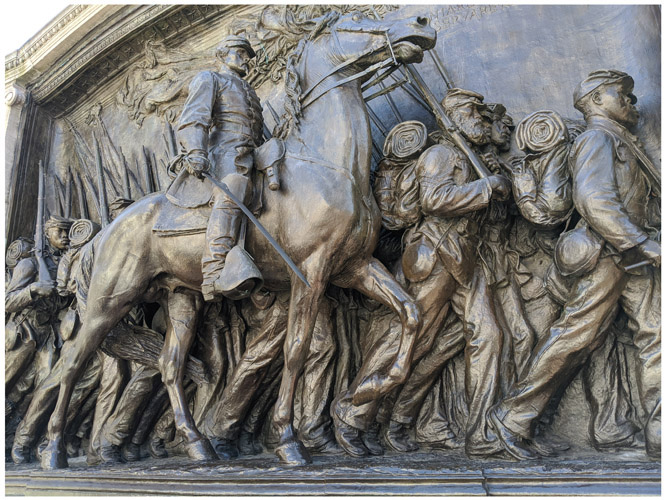

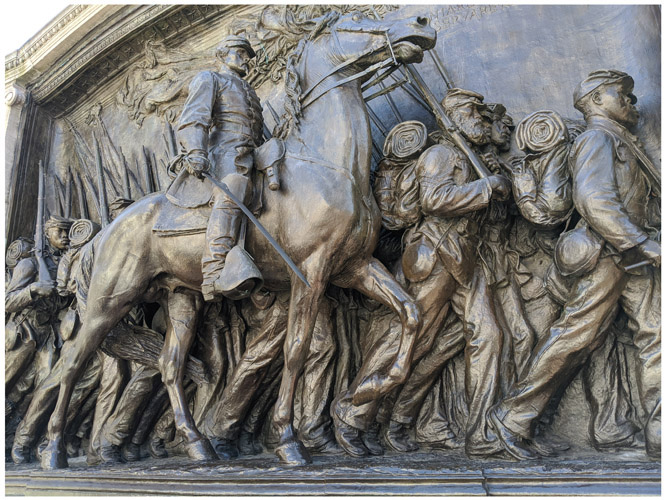

The most moving and artistically accomplished of the Commons sculptures memorializes the 54th Regiment of the Massachusetts Infantry. The first all-volunteer Black regiment in the Union army was led by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, a member of a wealthy abolitionist family. Shaw and nearly half his men died while leading an assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina on July 19, 1863. Shaws family rejected plans for a traditional equestrian statue of the colonel, insisting instead that he be shown with his regiment. Sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens summoned the full extent of his powers to capture the moment when Shaw and the line of proud soldiers marched past cheering crowds in front of the State House on their way to war. The memorial, which sits on the Beacon Street edge of the Common, was dedicated on May 30, 1897. It is the ostensible subject of For the Union Dead, one of Robert Lowells most famous poems. At the dedication, Lowell wrote, William James could almost hear the bronze Negroes breathe.

Just three months after the unveiling, a new era dawned on Boston Common. At 6:02 a.m. on September 1, 1897, the first trolley car rolled down the underground tracks between the Public Garden and Park Street stations. Before the day was out, more than 100,000 people had experienced the ride on Americas first subway (see page 6).

Lying at the juncture of the Red and Green lines of the MBTA, the Common has both the expanse and the supporting transportation to serve as the citys soap-box. Protesters have rallied against the Vietnam war, in support of Northern Irish hunger strikers, in favor of LGBTQ+ rights, and against racial injustice. Members of Occupy Boston gathered supporters to their fight for economic equality. Others have demanded greater action to combat climate change. White nationalists holding a free speech rally were met with double their number of counterprotesters. The Common is the stage where First Amendment rights are exercised to the ragged limits of the United States Constitution.