GOING DOWN FOR AIR

a memoir in search of a subject

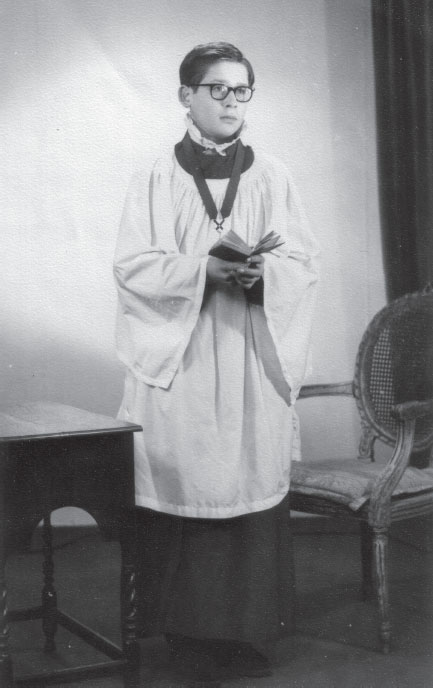

Nearer my God to Thee. Rochester, Kent, England, circa 1960.

GOING DOWN FOR AIR

a memoir in search of a subject

Derek Sayer

First published 2004 by Paradigm Publishers

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2004, Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

Designed and Typeset by Straight Creek Bookmakers.

ISBN 13: 978-1-59451-040-3 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-59451-041-0 (pbk)

To Yoke-Sumnot forgetting Daniel

Great Barrington Books

Bringing the old and new together in the spirit of W. E. B. Du Bois

An imprint edited by Charles Lemert

Titles Available

Sociology After the Crisis, Second Edition

by Charles Lemert (2004)

Keeping Good Time: Reflections on Knowledge, Power, and People

by Avery F. Gordon (2004)

Going Down for Air: A Memoir in Search of a Subject

by Derek Sayer (2004)

The Souls of Black Folk

100th Anniversary Edition

by W. E. B. Du Bois, with commentaries by Manning Marable, Charles Lemert, and Cheryl Townsend Gilkes (2004)

CONTENTS

I AM GRATEFUL FOR THE SUPPORT given to my writing by the Canada Research Chairs program, which I have enjoyed since January 2001. The Canada Foundation for Innovation provided the funding for the Visual Culture Research laboratory at the University of Alberta, where the photographs in this book were edited for publication. Permissions for use of song lyrics and other copyrighted materials are listed separately below.

I entered brief excerpts from what eventually became A Memoir in the 2000 Mactaggart Writing Award competition at the University of Alberta. That text formed the basis of a presentation entitled Anamneses at the 2000 Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences, again at the University of Alberta. I much appreciate the encouragement I received from a surprised audience, in particular my colleagues Bill Johnston and Rosalind Sydie. It helped me (in Winston Churchills immortal words) to keep buggering on. I did not win the writing award, whose prize was $10,000 to be spent on travel in search of new and stimulating experiences (as distinct from academic research)a wonderful idea. But Mrs. Ccile Mactaggart was sufficiently taken with my entry to offer a special award, which supported my trip in the fall of 2000 to New Zealand. This book would have been quite different had I not made that journey, halfway across the world and in some ways even further back in time. I am deeply appreciative of Cciles faith in my writing, and can only hope she thinks the result worthwhile.

I owe thanks to my mother, Mrs. Kathy MacDiarmid, for jogging my memory on this, that, and the other during my time in New Zealandamong many other thingsas well as to my brother-in-law Darryl Hughes, who alerted me to articles in The Wooden Boat on Maybird, articles that Victor Jackson then triumphantly unearthed for me from the treasure trove that is his study. Doug Aoki, Shyamal Bagchee, Clay Ellis, Karen Engle, Colin Richmond, and Yoke-Sum Wong were all kind enough to read various drafts of A Memoir. I doubt they will ever know how much their warm responses meant to a writer venturing into uncertain waters, though Yoke-Sum, I suspect, has an inkling. Dariusz Gafijczuk, Lilia Verchinina, and Joshua Nichols all read In Search of a Subject, and offered the informed and incisive suggestions one expects of good graduate students. Some of these suggestions were gladly taken up. Departing from conventional genres of academic writing, I soon discovered, can rapidly leave one short of publishers. I am correspondingly grateful to Charles Lemert and Dean Birkenkamp at Paradigm for their support of this book, as well as to Christine Arden for her expert and sensitive copy-editing.

A Memoir is full of people who long ago took up residence in my memoryfamily, friends, teachers, colleagues. Some are now dead, others I have lost touch with over the years. What they have meant to me should be plain from the text. But I did not ask their permission to put them in my book. It is all the more important, then, to emphasize that I portray them in these pages not as they areor even, perhaps, as they were. They appear here as I remember them. And as I hope this book shows, memory is not to be trusted.

Front Cover: Out of service. Gatwick Airport, England, 2001.

Frontispiece: Nearer my God to Thee. Rochester, Kent, England, circa 1960.

Oh, I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside! Snapshots from a family album, circa 19401960.

I put down the cup and turn to my mind. It is up to my mind to find the truth. But how? What grave uncertainty, whenever the mind seems overtaken by itself; when it, the seeker, is also the obscure country where it must seek and where all its baggage will be nothing to it.

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time1

THE BEST-KNOWN EPISODE in Marcel Prousts In Search of Lost Time is that moment in which the narrator suddenly finds the little town of Combray, where he spent his childhood, flooding back, the memory unexpectedly released by the taste of a petite madeleine dipped in tea. Proust compares this process of involuntary memory to that game in which the Japanese amuse themselves by filling a porcelain bowl with water and steeping in it little pieces of paper until then indistinct, which, the moment they are immersed in it, stretch and shape themselves, colour and differentiate, become flowers, houses, human figures, firm and recognizable.2 A less benign, though no less involuntary, image of recovered memory is offered by Walter Benjamin in his essay One-Way Street. We have long forgotten, he says, the ritual by which the house of our life was erected. But when it is under assault and enemy bombs are already taking their toll, what enervated, perverse antiquities do they not lay bare in the foundations! What things were interred and sacrificed amid magic incantations, what horrible cabinet of curiosities lies there below, where the deepest shafts are reserved for what is most commonplace?3

For reasons I do not pretend to understandthe slow advance of age, perhaps, or maybe upheavals in my personal life at the timemany things I thought I had long forgotten, or to which, at least, I had formerly attached little importance, started to come back to me around the turn of my fiftieth year. The experience was more Benjaminian than Proustian. There was never as dramatic or complete a single moment of recollection as Prousts sudden rediscovery of the Combray he had thought was completely dead to him. It was a matter, rather, of a subtle shift in the tenor of the present, in which the familiar, everyday things surrounding mea picture in a book, a tune on the radiotook on added layers of significance, pointing somewhere other than their here and now, back into the recesses of my past. I found myself increasingly drawn

An imprint edited by Charles Lemert

An imprint edited by Charles Lemert