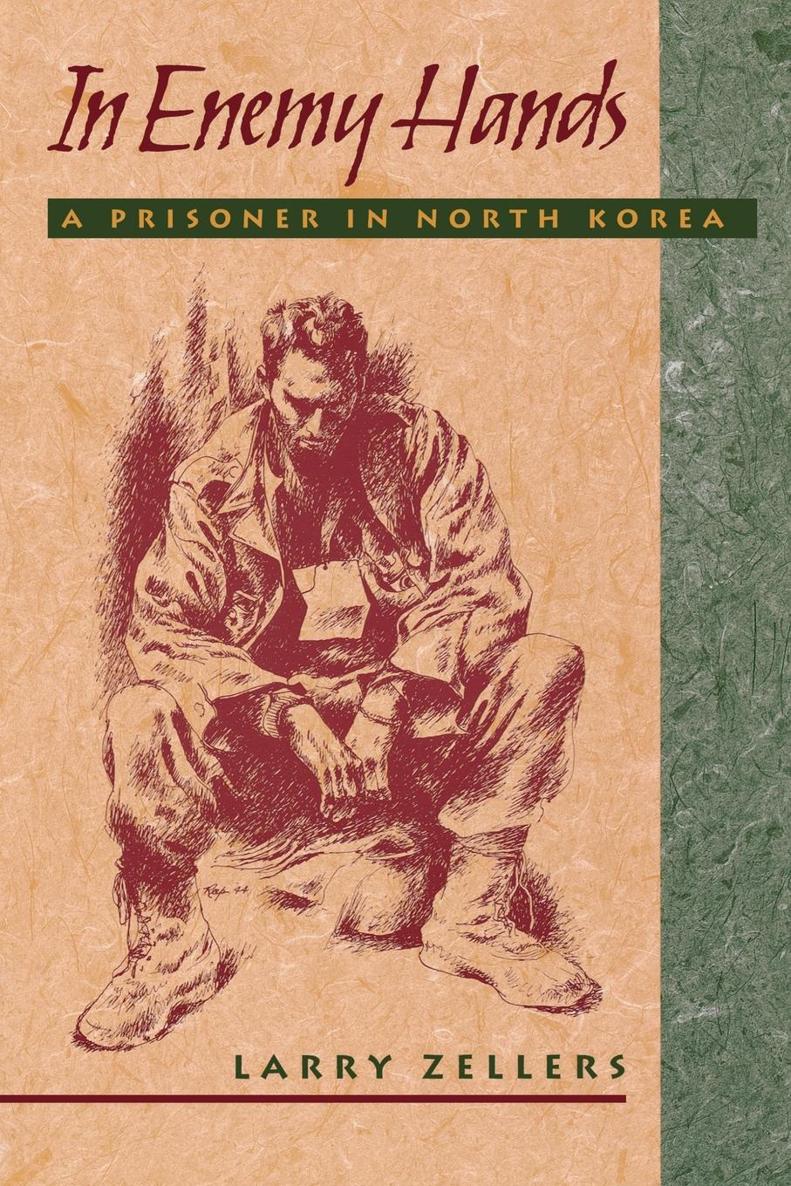

In Enemy Hands

In Enemy Hands

A Prisoner in

NORTH KOREA

LARRY ZELLERS

With a Foreword by John Toland

Publication of this volume was made possible in part

by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 1991 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Club Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

03 02 01 00 99 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zellers, Larry, 1922-

In enemy hands: a prisoner in North Korea / Larry Zellers ; with a foreword by John Toland.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8131-0976-0 (paper : alk. paper)

1. Korean War, 1950-1953Personal narratives, American.

2. Korean War, 1950-1953Prisoners and prisons, North Korean.

3. Zellers, Larry, 1922- I. Title.

DS921.6.Z45 1991

951.904'2dc20 90-26375

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper

meeting the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

To Frances, whose spirit

supported me every step of the

way and whose unflagging faith

in my return never faltered.

Also to those who, in that

unhappy land and for whatever

reason, did not make it.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

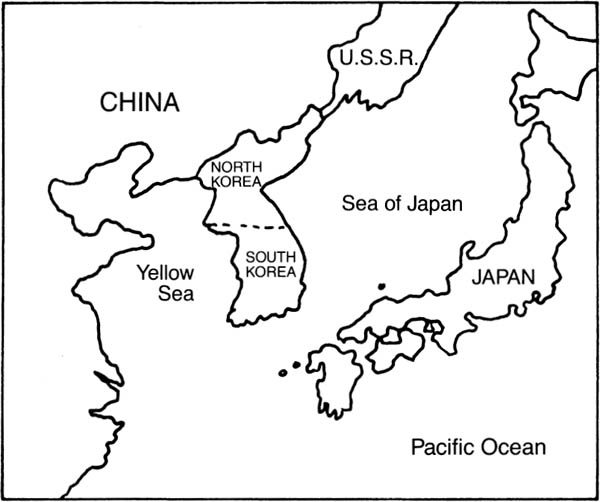

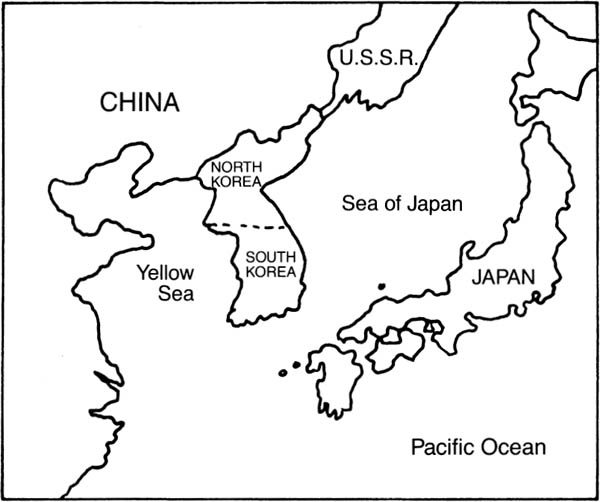

FOR most Americans, myself included, the emotional exhaustion left by World War II blocked out the three seemingly endless years of the Korean War. We were absorbed by the recovery of America and Europe rather than the perilous involvement in the Far East. We did not realize that this war was unique in our history. In fact, it wasnt even a war, only a police actionaccording to President Harry Truman. Yet fifteen of the United Nations had joined in fighting North Korea and China, and four million human beings perished in a brutal contest that eventually led to the tragedy of Vietnam.

Half of those who died in Korea were civilians and, although much has recently been written about the Korean War, too little has described the terrifying experiences of civilians trapped in the war. That is why In Enemy Hands by Larry Zellers, a Methodist missionary, is so important. His harrowing tale of western civilian prisoners of the North Koreans and Chinese is a fitting monument to the men, women, and children who endured starvation, beatings, humiliation, and privations for almost three years.

Zellerss detailed account of the Death March in North Korea in the winter of 1950 is an unforgettable saga of human tragedy and valor. During a journey of more than a hundred miles over rugged terrain in the bitter cold and snow, almost a hundred dead civilians and American soldiers were left along the way. Those who survived endured endless hardships until freedom at last came in 1953.

What makes Zellerss relentless chronicle so compelling is the moving portrayal of his comrades in the face of adversity. Unprepared and untrained for the rigors and terrors of imprisonment by an alien foe, they somehow managed to survive because of their indomitable spirit, their faith, and their common self-sacrifice. All this has allowed Zellers to make an unbearable tale inspirational.

John Toland

PREFACE

WHEN I was released from North Korea in 1953, after three years in confinement, I discovered that I had more things to do than I could accomplish. I wrote down my experiences soon after I returned, but I never found time to arrange them for publication. I thought I might finish that task when I retired from the U.S. Air Force in 1975, but by that time the Korean War was ancient history, even to me.

I would never have undertaken it except for a chance meeting in 1987 in Seoul, Korea, with members of the United Nations Command Military Armistice Commission (UNCMAC). The Air Force had sent me to Korea in January 1987 to share my prison experiences with U.S. military personnel there. Following a speech at Camp Red Cloud near Seoul, I was interviewed by U.S. Armed Forces Korea Television. In response to a question, I mentioned the two neighboring North Korean villages of Hanjang-ni and An-dong, where approximately 400 American military and civilian prisoners from several nations had been buried during the winter of 1950.

Subsequently, I was put in touch with Lieutenant Colonel Gilbert H. Eckrich, U.S. Army, assistant secretary of UNCMAC. Eckrich informed me that his commission was particularly interested in obtaining additional information about the location of American and other United Nations prisoners of war in North Korea. My mention of those two villages interested them. In extended discussions at the negotiation site at Panmunjom from 1985 to 1987, the North Koreans had never revealed to the Armistice Commission that Americans had even been held in the Hanjang-ni and An-dong area, much less that hundreds had been buried there.

In an effort to show good faith and to support the negotiations, the United Nations Command had brought to Panmunjom the remains of a small number of Chinese and North Korean soldiers killed in South Korea. The Chinese representatives there accepted the remains of their soldiers; the North Korean representatives, on the other hand, rejected a similar offer, claiming the remains were not really those of North Korean soldiers. The United Nations documentation was extensive, including photographs of North Korean soldiers being buried with full military honors in South Korea. The North Koreans returned the remains of five Americans on Memorial Day 1990 but have otherwise been very slow to respond.

I took part in more discussions with Col. Donald W. Boose, Jr., U.S. Army, secretary of UNCMAC, who asked for a list of survivors at Hanjang-ni. Using the names and addresses I provided, Colonel Boose and Lieutenant Colonel Eckrich built a file of documents received from survivors of the Hanjang-ni area in North Korea. On May 26, 1987, at the 482d Secretaries Meeting at Panmunjom, Colonel Boose submitted this information to the representatives of the Korean Peoples Army and the Chinese Peoples Volunteers. They accepted the documents and said they would pass the information to an appropriate authority.

Before leaving Seoul in February 1987, I was encouraged by Lieutenant Colonel Eckrich and Tom Ryan of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, to prepare my manuscript for publication. I had often been given the same advice by friends in the United States; perhaps I had too hastily rejected it on the grounds that no one was reading anything about the Korean War any more.