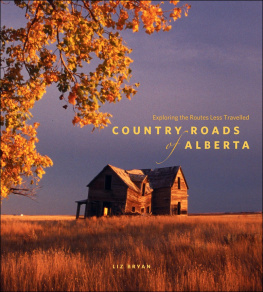

Montanas Chief Mountain, a Native icon, rises above fields of grain emblazoned by the sunrise.

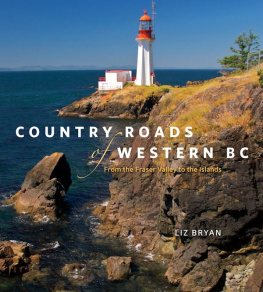

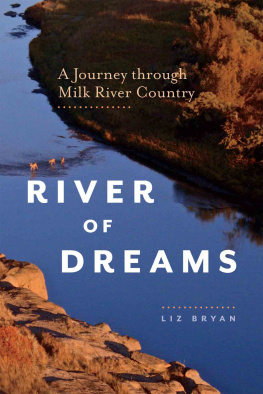

MEANDERING ALONG THE MILK RIVER

The Milk River rises in Montana and curves briefly into Alberta before slipping south again to join the Missouri River on its way to the Gulf of Mexico. It is one of only three Canadian streams to feed into the Mississippi watershed and the only one in Alberta. It is a beautiful stream, still wild, and it flows through some of the most interesting country in all of Canada badlands and relic prairie, virtually untouched by civilization, where rare plants and wildlife still flourish. The river was named in 1805 by Meriwether Lewis of the American Lewis and Clark Expedition because it was, as he described it, about the colour of a cup of tea with the admixture of a tablespoonfull of milk. The explorers saw the river in high water, churned up with glacial silt and brown mud from its banks, but at other times, the water is clear. Its wide, sheltered valley, tufted green with cottonwood and willow, is a linear oasis in the arid grasslands of the border country. And it has a geological tale to tell.

Toward the end of the most recent ice age (which just about smothered all of Alberta), the mountain glaciers to the southwest melted first, sending torrents of water onto the plains. But the ancestral river channels were still blocked by a thick sheet of continental ice to the east, and the meltwater backed up, forming a lake whose southern rim was the Milk River Ridge. As levels rose, the raging waters burst through the ridge and poured south into the Milk River through such breaks as Whiskey Gap, Lonely Valley and half a dozen coulees. Engorged by this fierce water flow, the Milk cut deeply into the land, down through ancient earth layers to the days of dinosaurs and far beyond. Eventually the continental ice melted, and the major rivers of southern Alberta resumed their original courses, heading for Hudson Bay. The meltwater lake drained and the Milk River shrank to its former size, still flowing south. Today, the river is known to geologists as an underfit stream and meanders through a surprisingly broad valley, cut nearly 400 metres deep below the prairie level. Here, millennia of wind and water erosion have carved sandstone canyon walls into badlands every bit as stupendous as those of the Red Deer River farther to the north.

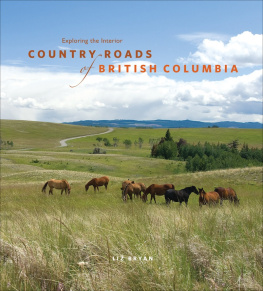

The magic of sunset turns the Milk River cliffs to gold.

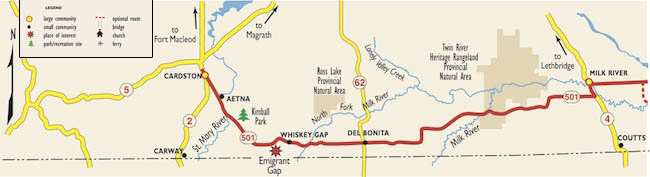

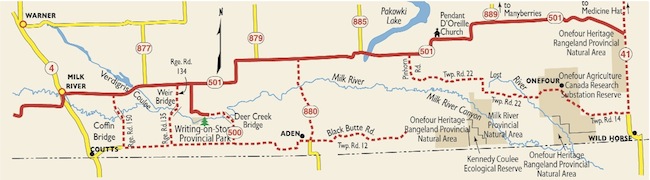

Keeping as close to the CanadaUnited States border as possible, this journey follows the lovely Milk River through some of the wildest lands of Alberta. Its a long day from Pincher Creek to Medicine Hat; allow for more time if you plan to visit Writing-on-Stone.

Where the badland hoodoos are thick and mysterious and the blue humps of the Sweetgrass Hills empower the horizon to the south, the Milk River Valley became a sacred place for the First Peoples of the plains. It was here that young men came for vision quests, fasting in solitude among the rocks, looking for guidance from the spirit world. Scratched into vertical sandstone bluffs along the river are pictures of epic events from the days when buffalo and wildlife were plentiful and tribesmen fought behind giant shields with bows and arrows. Archaeologists believe this rock art was inspired by visionsdreams turned to stone to outlive the dreamer. Other writings may be records of tribal events, the newspapers of the day. Certainly, later pictures portray the arrival of Europeans, the first guns, horses, wheeled wagons, forts, flags and gallows, even automobiles. Much of this art is protected within Writing-On-Stone Provincial Park, where the largest collection of Aboriginal rock art in Canada sheds light on the human history of the plains.

Because the Milk River in Alberta flows through arid landthe country that Captain John Palliser on his 1857 journey of discovery called unfit for settlementmuch of the rivers watershed was never carved into homesteads or broken by the plough but was left as open rangeland. It is wild land still, rich with native grasses, flowers and wildlife, where tangible traces of Aboriginal lifethe tipi rings of campsites, buffalo jumps, cairns and medicine wheelscan still be found.

There is little public road access around the river; perhaps the best way to appreciate the landscape is by canoe. But Secondary Highway 501, which stretches eastwest across Alberta just north of the Montana border, cuts through it, provides some river access and, best of all, leads to Writing-On-Stone Provincial Park, the high point of any excursion along the boundary. Start this journey on Highway 2 south of Cardston where the 501 branches east and leads across the province to the Saskatchewan border. Its a route to consider at any time of year, though summer is best at Writing-On-Stone, when park interpretive programs are in full swing. Wildflowers are at their peak among the sagebrush in late spring, fall brings cottonwood gold to the river valley, and you can count on seeing herds of pronghorn antelope at any time.

Cardston lies on the edge of mountain country: the Rockies dominate the horizon. South of the city, Secondary Highway 501 turns its back on the peaks of Waterton and heads southeast across the prairie. About five kilometres ahead, a signpost points north to the former Mormon community of Aetna, positioned alongside the trail that immigrants followed north from Salt Lake City around the turn of the last century. The hamlet, named for the Italian volcano, had a store, school, church, blacksmith shop, even a creamery and a cheese factory, although today little remains. Of the church, only the bell has survived, on display outside the modern Aetna gas station and store at the junction.

The road continues straight southeast and crosses the St. Mary River, a tributary of the Oldman, which in turn flows into the Bowall waters that drain north into Hudson Bay. Tucked beside the river, Kimball Park with its shady campground provides good birding in a classic mix of fescue grassland and dense cottonwood forest. Beyond the river, the road rises to cross the swell of the Milk River Ridge. (In Montana, the ridge is known as the Hudson Bay Divide.) No steep mountain pass marks this grand division of the watersthe ridge here rises gradually, at its height a scant 400 metres above the prairie. As you drive along, the low heave of the ridge is north, the sensational thrust of Montanas Chief Mountain and other lofty peaks of the Rockies to the southwest across the fields.

Eroded by long years of wind and rain, the sandstone valley rim is a maze of fantastic hoodoos and pinnacles.

Highway 501 veers sharply east as it nears the Montana border, but straight ahead at the bend is the continuation of the Old Mormon Trail that led settlers into Canada through Emigrant Gap, a scenic option, though the road no longer goes through into Montana but ends at a ranch gate. Highway 501 curves around the southern edge of the ridge and heads east for the largest of the meltwater cuts, Whiskey Gap, notorious for its illicit liquor trade. Whiskey was smuggled north from Fort Benton in Montana by mule team and pack horse, destined for the crudely built forts where traders bartered a rotgut version of the brew to local Natives. This illicit trade was stoppedor at least curtailedwhen the North West Mounted Police (NWMP) came west, established a fort on the Oldman River (todays Fort Macleod) and set about policing the border from a string of tiny outposts. During American Prohibition, liquor flowed again across the border, this time from Canada into Montana. When in turn Alberta became dry, the whiskey trade once more flowed the other way.